An interview with Anna Ridler, the artist behind Mosaic Virus and Myriad (Tulips)

Anna Ridler, recipient of the 2018 European Media Art Program and the winner of the 2018-2019 Dare Art Prize, takes us through her latest art pieces to be displayed in Barbican’s AI: More than Human exhibition.

For those unfamiliar with your work, how would you introduce yourself and describe your artwork?

I’m an artist. I like to work with technology, but not just because it is there. I think about what it can do and how it can add to what I’m making, about its associations and the connotations of using it: how can all of these different things go in and help amplify or construct the message I’m interested in and make it conceptually stronger.

Was technology something that you always wanted to incorporate in your artwork?

I’ve always been interested in using data and technology, and as machine learning become more prevalent and barriers to using it dropped, it became a natural way of exploring this existing interest. My background is in literature and linguistics as well so the other quite nice thing is if you look at how machine learning systems work in labelling things, – deciding when a thing is a thing – it all just came together, which is why I think I find it so enjoyable to work with. It just naturally all fell together and I feel that it has become a really natural way to draw together lots of different aspects of my practice.

A lot of your research is focused on how art is perceived or validated through a scientific lens. Could you briefly describe what ‘art’ means to yourself?

This is a hard question! I suppose in short art is something that has intent – you’re trying to question the world through a medium and a process.

What are your major influences for your work?

I think my background in literature – I’m constantly reading fiction – has given me a really good grasp on narrative and trying to tell a story. Also the type of books that I like to read tend to be about quite minor things that still reflect major issues and I think this reflects back in my work. I also read a lot of random science facts as I find these to be really inspiring to give new ideas and directions.

I’m really excited to see Mosaic Virus and Myriad (Tulips) at the Barbican in person. What is the significance of tulips for you?

Mosaic Virus draws historical parallels from the ‘tulip-mania’ that swept across the Netherlands in the 1630s and the speculation currently ongoing around crypto-currencies. “Mosaic” is the name of the virus that causes the stripes in a petal which increased their desirability and helped cause the speculative prices during the time. In this piece, the stripes depend on the value of bitcoin, changing over time to show how the market fluctuates.

I want to draw together ideas around capitalism, value, and the tangible and intangible nature of speculation and collapse from two very different yet surprisingly similar moments in history and I found tulips a way to do this. It also updates another tradition – one of the very first dataset used for computer vision was made from irises.

Furthermore, there is a tradition of tulips in art history. Tulips featured prominently in Dutch still life at the time, the so-called ‘vanitas’ paintings that illustrated that beauty and treasure are only fleeting. This piece will update this tradition but with a twist. The GAN [generative adversarial network] constructs an image not of a real tulip, but what it thinks a tulip should be, much like how seventeenth-century still life pictures do not show actual displays of flowers but imagined bouquets (it would be impossible for some of the bouquets in still-lifes to exist in reality as the flowers shown bloom at different times of the year).

It must’ve been exhausting work, taking 10,000 photographs of tulips. What was the process like and how did you make it through?

It was a very time consuming process! But what was quite nice is the even though this is a very digital piece, there is was a very natural rhythm to it – I stopped making my dataset because the tulip season ended. I went to the flower market one weekend and there were no more tulips, only peonies, so I had to stop. So even though it’s a very digital piece, it was very much driven by the rhythms of nature. Also – and this shouldn’t have surprised me given the context – but it was actually extremely difficult to find striped tulips and I ended up going all over the Netherlands trying to find stripey ones!

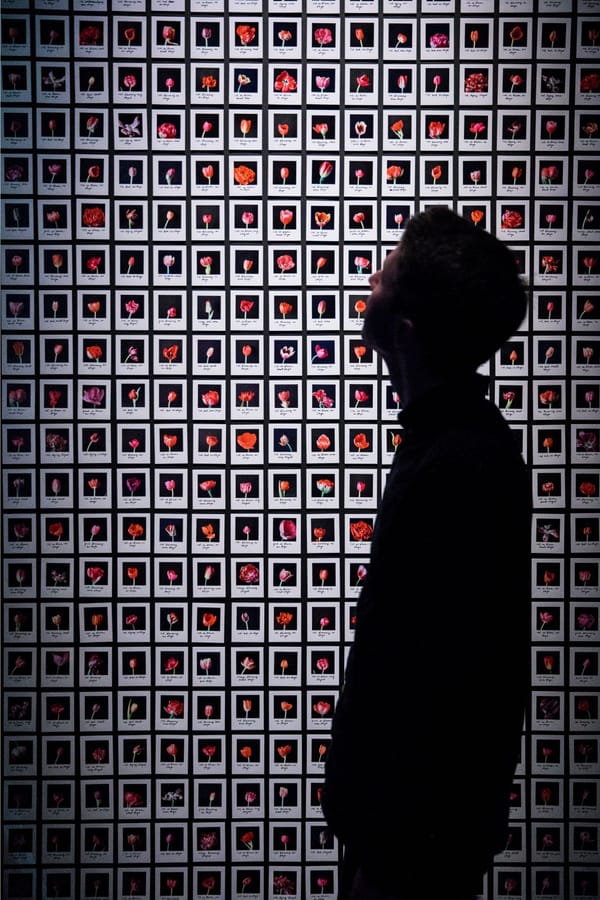

Making this dataset was so important to this project. I worked testing the dataset in order to get the type of output I wanted – and that changed what type of flowers I was buying, what shape, what colour. The other thing that I had to do for this was categorise every single photograph by hand. What colour, what type of tulip, how striped it was, whether it was in bud or dying. This was an insane amount of work and it is usually work that is hidden. The whole process of creating the dataset took around four months. By choosing to make it a separate work that is displayed in relation to the video work, I draw attention to this act of categorisation – and also the human element of it, by handwriting each of the labels. I can use it to start to have discussions – particularly in non-technical communities – about the fact that there is always a human decision somewhere along the chain of using AI and that it is not this absolute correct thing...even something as simple as a tulip is difficult to put into discrete categories – is it white or pale pink, is it orange or yellow – and how if it’s difficult for something as simple as a flower, imagine how difficult it will be for something as complex as gender or identity! It has become parallel work, unpicking ideas to do with labour, technology and categorisation and also the humanness that is behind every algorithm, every decision made by an AI.

But despite all of this categorisation it is a mistake to think that I have control. It is impossible to predict what will come out in each of the stills – I can guess, but I cannot know. And this to me is really exciting. It is these ‘mistakes’ that drive me to use this as a material – it becomes weird and eerie in a way that I wouldn’t be able to do myself, and draws on the history of time-lapse photography but through a lens.

Do you ever feel wary of technology and automation encroaching on human expression as some people believe?

No, for me it is very much a tool and a process. I don’t find it encroaching on human expression, I find it a way of expressing myself more fully, in ways that I was never able to before.

What thoughts or impressions do you hope your audience will leave with after seeing your works at the Barbican?

I hope that they can see the poetic potential of this as a medium!

Finally, do you have any ideas for future projects and is there any technology that you’re hoping to use in later works?

I’ve making a new project with Opera North that will debut in the autumn. It’s really exciting to push the work I’m doing but using sound and performance.