Vita & Virginia Review

Chanya Button’s film adaptation of the play about literary lovers prioritises style over substance

Sometimes called the longest love-letter in history, Virginia Woolf wrote Orlando, the fictional biography of a gender-bending, time travelling Elizabethan nobleman, as a tribute to her friend, and sometimes-lover, Vita Sackville-West. Based to a great extent on the letters that the two acclaimed novelists wrote each other over twenty years, director Chanya Button’s film, Vita and Virginia, explores the complex relationship the two women shared, and the conception of Woolf’s seminal novel.

Ostensibly a period piece, beginning with the meeting between Sackville-West (Gemma Arterton) and Woolf (Elizabeth Debicki) in 1922, the Vita and Virginia attempts to take a page out of Sofia Coppola’s 2006 biopic, Marie Antoinette. It is to the beat of synth heavy electronica that Vita and Virginia’s eyes meet across a smoke filled dancefloor. Whilst Isobel Waller-Bridge’s musical interjections bring urgency to the narrative and serve to highlight the modernism of thought and sensibility amongst the the Bloomsbury Group to which both Sackville-West and Woolf belonged. This is not mirrored by the rest of the film which remains resolutely staid.

In antithesis to Button’s 2015 debut, Burn Burn Burn, Vita and Virginia has a curiously stilted quality, particularly as the first meeting gives way to exposition. This is no small part to its heavy reliance on lifting words directly from the letters that the two novelists wrote each other. “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia” wrote Sackville-West to Woolf in one such exchange. On the page these letters are electrifyingly passionate; as dialogue, they become heavy, and overwrought, losing something of their brilliance. Eileen Atkins originally developed Vita and Virginia as a play, and here, the script adapted by Atkins and Button for film still clings to the vestiges of the stage.

Debicki and Arterton take turns to perform the text directly to us, the viewer, their faces partially obscured by gauzy, soft-focus camerawork. Delivered in this way, the letters come across not as lovelorn confessionals but as performative monologues. It is easy to see how this would’ve been successful in a theatre, but on film, the lack of naturalism serves only to create distance with the audience.

Vita and Virginia hits its stride in its latter third when the two protagonists come together as lovers, spending their nights in Vita’s ancestral home, Sissinghurst Castle, which will later form the setting of Orlando. Their brief romance is tender, propelled by the chemistry between the lead actresses who lend enormous charisma to their roles. Arterton is winsomely flirtatious, yet retains a chink of coldness that manifests itself later in the film. Debicki is luminous in a vulnerable portrayal of Virginia; rail thin, holding her body with awkward tension, she looms over Arterton, capturing a sense of being entirely otherworldly.

When the two are apart, the movie flags. The supporting cast includes a roster of stars including Emerald Lilly Fennell as Vanessa Bell, and Isabella Rossellini who shines in a bit part as Baroness Sackville, Vita’s extremely well heeled mother, but they are given precious little to do other than push Vita and Virginia together, or endeavour to keep them apart. We are often told of the scandalous free spiritedness of the Bloomsbury Group, yet seldom see this for ourselves beyond catty exchanges over painting sessions and raunchy dancing at parties.

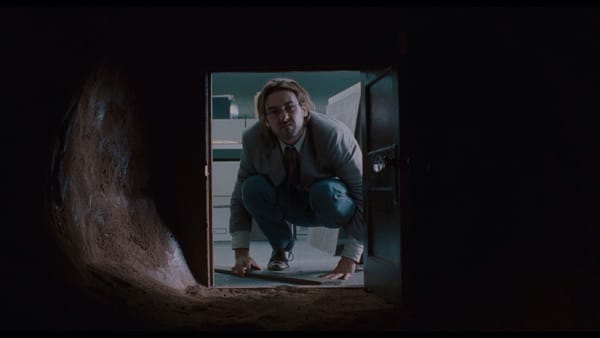

The undercurrents of tension between Sackville-West’s aristocratic upbringing and Woolf’s middle class socialist background are left relatively unexplored. Any mention of the former’s own, wildly successful writing career quickly falls by the wayside. Perhaps most crucially, the movie doesn’t know quite what to do with Woolf’s ailing mental health; in lieu of nuanced dialogue, Button opts for fantastical allegory. Long strands of ivy threaten to overwhelm her whenever Virginia feels anxious; during a panic attack a vast cloud of crows plummet towards Virginia’s head as she cowers in the garden. These superficial renderings do not do justice to Woolf whose life’s work was an articulation of things hidden beneath the surface.

Vita and Virginia is a visually beautiful film, filled with wide, sweeping landscapes and moodily lit interiors shot by Carlos De Carvalho, but we are left uncertain of Button’s intentions. The film occupies the grey middle ground between a character study, and a period romance without quite committing to being either. A little more irreverence from Button would’ve elevated this from a run of the mill Woolf and Sackville-West biopic to a truly perceptive portrayal of the lives of these two remarkable women.

- 3.5 stars