Flying regularly not crucial for success in academia

New study finds increased travel does not increase impact of research

Science is quite rightly celebrated for being an international enterprise, and academics often feel required or obliged to fly frequently and over long-distances in order to conduct their work or maintain professional relationships. But how important is long-distance travel to a scientific career, and how much do scientists contribute to climate change through their travels?

30% of academics who surveyed by the Tyndall Centre felt an expectation to fly from their university. A new study at the University of British Colombia (UBC) suggests this pressure may not be rationally founded. Although academics who change affiliation are found to have 40% more citations, academics who fly more frequently do not have a greater number of citations, nor do they have a greater number of co-authors per paper.

Attending conferences, undertaking fieldwork and teaching all contribute to the demand for travel by air, with 60% of demand coming from travel for conferences. In a sample of 705 academics at UBC, claims for air travel were made for 2.9 trips per person each year on average. Of these, 10% of trips were same-day returns, long-distance flights with only one overnight stay, or short-distance flights for which ground-based transport could be taken. Such trips have a high carbon footprint within a short timeframe.

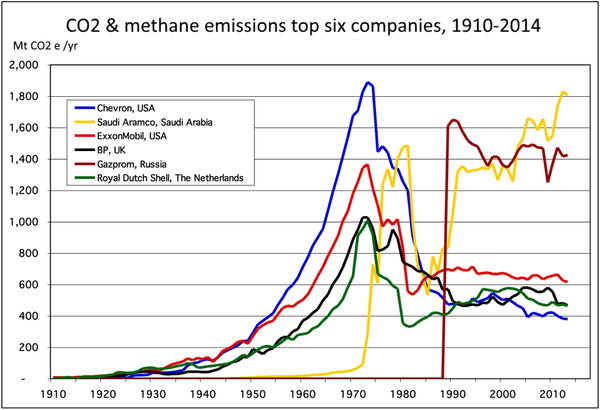

The scientific consensus on climate change is clear, and so are the impacts of flying. Aviation is the most environmentally damaging form of long-distance transportation. A single passenger travelling 100 km by plane is responsible for the production of over 20 kg CO2e in emissions, double that by road (10 kg) and seven times that of a passenger travelling by rail (3 kg) (see To the planet every journey matters below). This is despite the high seating efficiency of airlines thanks pre-booking systems, less rigorously imposed in rail and bus travel, and decades of optimization of aircraft design and operation. Emissions from aircraft also affect human health directly. For instance, emissions from aircraft increase near-surface ozone levels and atmospheric sulphate concentrations. While Ozone in the upper atmosphere blocks harmful UV frequencies, at the surface it results in respiratory diseases. Sulphate aerosols, though slightly reducing the greenhouse effect, have the potential to cause drought according to a briefing paper produced by the Grantham Institute at Imperial College.

Using, for the first time, written records (travel expenses) as opposed to self-reported statistics, which can suffer from limitations, researchers found no correlation in the sample between the h-index of academics and the distance flown, even when accounting for age of the academic and number of co-authors on each paper. Nor was there a correlation between number of citations per author per paper and distance.

Perhaps flying helps to produce larger collaborations? This too also does not appear to be the case, the average number of co-authors per paper was no higher for academics who flew further. A significant correlation found was between emissions and salary. An possible explanation is that higher-earning senior researchers are frequently invited to give talks and more likely to afford to fly in higher class.

Acting to reduce air travel can come with economic and social co-benefits, including better perception of the scientific community.

Although academics are aware and often sympathetic to environmental issues, they are sometimes criticised for the knowledge-action gap on flight. A ten-year study of newspapers in four different countries, including the UK, found that a third of criticisms levelled at academics mentioned their flying behaviour.

Changes need not be costly. The lowest hanging fruit is to travel modestly. Economy class passengers cause almost three times lower emissions than business class, and four times lower than first class passengers. Encoding committments to use the lowest carbon means of transportation into grants could be an effective and easy strategy and set an example. Restrictions on class of seating is already included in some grants.

Given that reducing flying is desirable both for the environment and for academics, the results of the research are welcome, especially since Green academics were found to be no less likely to fly than non-Green.

Air travel may not be totally elimintated. Some long-distance travel will be needed for instance for fieldwork. One should be cautious to limit opportunities for less secure researchers who already travel less. Academics who did not claim any air travel expenses were found to receive fewer citations. A limited amount of air travel, used effectiely, may be beneficial. Above a certain threshold it is a case of diminishing returns.

A cultural shift is needed, but the changes required already have a precedent. Awarding grants which encourage low carbon travel, video-conferencing and limit use of high class air travel are strategies which could be employed to help researchers give flight to their research without liberating greenhouse gases.

To the planet, every journey matters

More fulfilling than jetting off in search of Love Island...