Rosmersholm

A stunning production of Ibsen’s lesser known classic is more relevant than ever.

Ibsen wrote Rosmersholm (pronounced Ros-mers-home) in 1886, and it is considered to be his masterpiece, over The Wild Duck and A Doll’s House. Yet it is rarely staged. The day I saw Rosmersholm was ironically the day of the European Elections, and the parallels were astonishing, regardless of the 134 years between the two settings.

Ibsen’s Nordic noir is rarely revived - although when it is, it is timely. In 2008, the world was suffering the effects of the financial crisis; in 1992, there was the Queen’s annus horribilis amongst other political fiascos. It’s a play that inspires change in its audience, in the way of life imitating art.

The play is set on the night before an election, with opposing parties vying for the vote and for the backing of John Rosmer (vividly portrayed by Tom Burke) – town priest and landed owner of the eponymous Rosmersholm. Unfortunately for the two parties, Rosmer himself has lost his faith and renounced his family’s wealth, practically throwing heirlooms at his staff. This sudden change follows the suicide of his wife the previous year, and the urging of Rebecca West (the breathtaking and show-stealing Hayley Atwell), whose progressive beliefs of equality and politics spur Rosmer to act in the best way for the people.

Hamilton’s Giles Terera is worryingly charming as an almost-fascist local governor determined to sway brother-in-law Rosmer, with Jake Fairbrother chilling and cool as the opposing radical left-wing newspaper editor Mortensgard. Both eventually abandon Rosmer to Rebecca and his house. Rosmer and Rebecca are so tragically intertwined in their desperation to escape, with the quote “Now I see love is selfish. It makes you a country of two. At war with the rest of the world”, encompassing this.

The revelations that arise throughout the second act of the play are almost absurd, especially regarding Rebecca’s past, but Atwell and Burke are so convincing in their respective losses, it is accepted and embraced.

There was a larger supporting cast here than the usual Rosmersholm portrayal, with amusing performances from Lucy Briers and Peter Wight, who play Mrs Helseth, the ever-patient housekeeper, and Ulrik Brendel, Rosmer’s former tutor and current drunk who lectures to the unappreciative masses.

The costumes by Rae Smith were divine, with the set and lighting used to an incredible degree to show not only the passing of time, but also the growth of the characters. The sound design was haunting yet not overwhelming, with almost-leitmotifs associated with concepts rather than specific people. The turning of the water wheel, in particular, and its importance to Rosmer, Rebecca and the town, is foreboding and cleverly brings our attention to the minutiae of the dialogue.

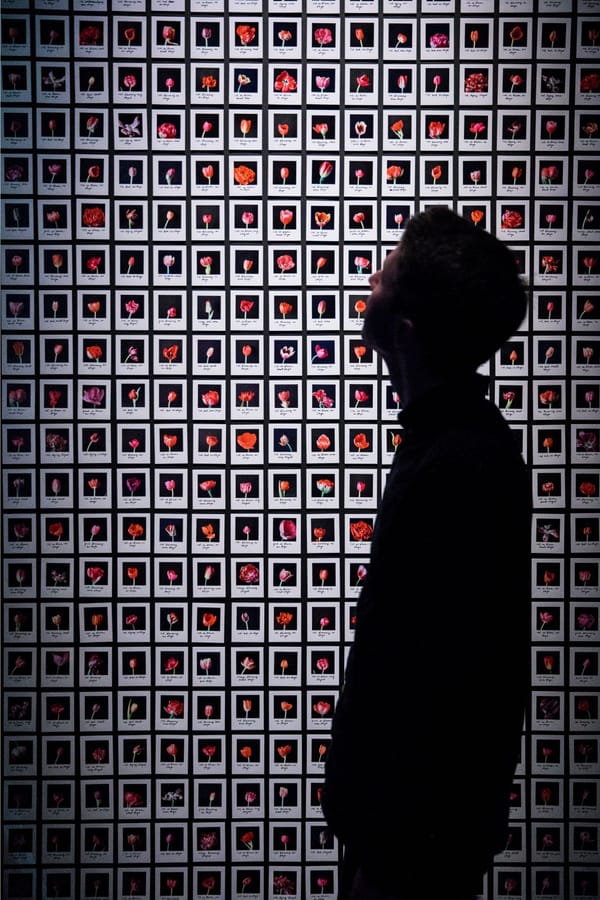

Stunning imagery is utilised, none more so than the final one, with the ominous sound of the water wheel coming to a stop and a lone man standing against the floods of change.

- 4 stars