In Summary: Nobel Prize 2019

Science editor Sânziana Foia gives an overview of the research behind this year’s science Nobel Prizes

Physics

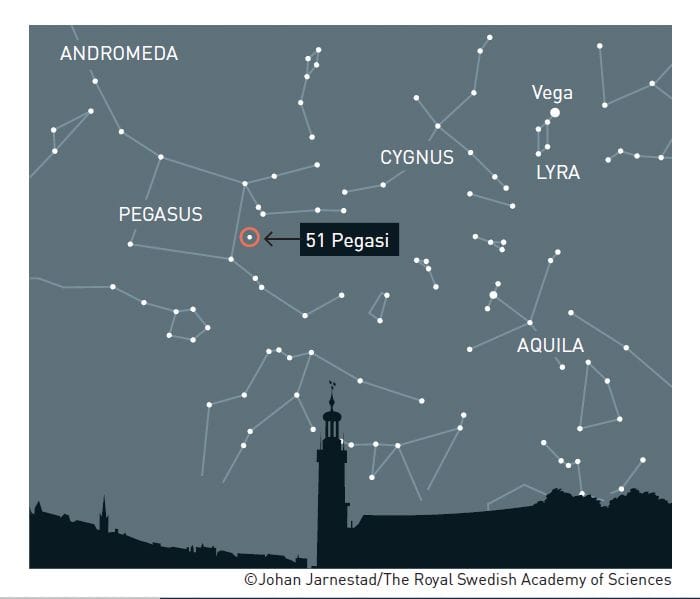

This year’s Nobel prize in Physics was awarded half to James Peebles (Princeton University) for work in physical cosmology and the other half jointly to Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star. Both have played an essential role in our understanding of the cosmos and Earth’s place in the universe.

Peebles has set the foundation for modern cosmology and developed theoretical tools that were used to discover new physics and were used to shed light on the history of the universe as well as its composition. By exploring fundamental properties of the universe and studying the radiation that was released immediately after the Big Bang, Peebles’ has constructed a model that allows us to describe the Universe from its first moment and up into the distant future. Moreover, Peebles’ work was a cornerstone in establishing the composition of the universe – of which only 5% is ordinary matter and the rest is comprised of dark matter and dark energy!

Back in 1995, Mayor and Queloz discovered a gaseous planet 150 times the size of Earth, the first to be identified outside our solar system, 50 light years away from our planet. While at the University of Geneva, Michel Mayor and his collaborators designed the ELODIE echelle spectrograph, a new piece of equipment that would allow them to study more than just the brightest stars, those closest to our solar system, and expand their observational capabilities. Using Doppler spectroscopy, they identified a planet that had the size of Jupiter but, surprisingly, was located much closer to the star – a distance ten times less than that between Jupiter and the Sun. This and the very short ornital period of a planet with the mass of Jupiter were some of the reasons that their discovery was met with skepticism. However, because of short orbital period of 4 days, it was possible for other researchers to very quickly verify and validate their discovery. This was the starting point of a new field of astrophysics, namely the study of exoplanets and planet formation.

Chemistry

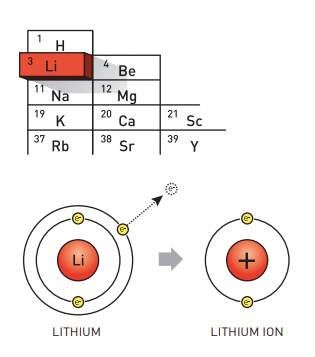

Used in everything from mobile phones to electric vehicles and laptops, little thought is often given to what keeps powering the world we live in – lithium ion batteries. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2019 rewarded John B. Goodenough (University of Texas, USA), M. Stanley Whittingham (Binghamton University, USA) and Akira Yoshino (Meijo University, Japan) for the development of an essential tool that gave rise to a “rechargeable world”.

During the oil crisis in the 1970s, Stanley Whittingham started exploring methods that could eliminate the need of fossil fuel energy in technology. When researching superconductors, he discovered titanium disulphide – a highly energy rich material which can accommodate lithium ions in its molecular architecture. Using this for the cathode of the battery and metallic lithium for the anode (which has a strong drive to release electrons) lead to a battery that was so powerful it was too explosive to be used in any applications.

John Goodenough take the discovery further and both increased its potential and its safety by exchanging the metal sulphide with a metal oxide – it was cobalt oxide intercalated with lithium ions that he found could produce as much as four volts. Using this as a starting point, Akira Yoshino was the first to create the first commercially viable lithium ion battery in 1985. To further increase their safety, he switched the anode material from lithium to petroleum coke, a carbon material.

The end product of this year’s Nobel laureates’ research was a lightweight, portable battery which have changed the technological world as soon as they entered market in 1991, having laid the foundation for a wireless, rechargeable society.

Medicine and Physiology

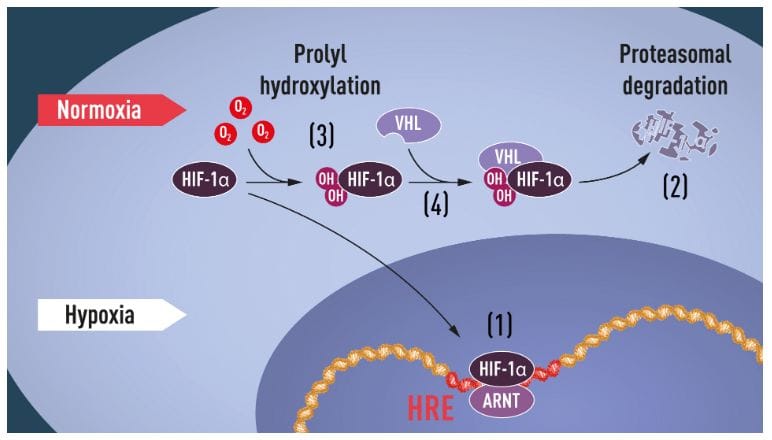

Although we have been aware of the importance of oxygen for life for centuries, there was little to no insight on how cells adapt to varying levels of it. This year’s Nobel laureates in Medicine and Physiology – Sir Peter J. Ratcliffe (University of Oxford, UK, The Francis Crick Institute, UK), William G. Kaelin Jr. (Harvard Medical School, USA) and Gregg L. Semenza (John Hopkins University, USA) were the first ones to identify the molecular machinery that regulates the activity of genes in response to changing levels of oxygen and how this affects cellular function and metabolism. Their research is seminal in both giving a more thorough understanding of biological processes and paving the way towards novel treatments that could combat several conditions, including cancer or anemia.

Examples of adaptive processes that are controlled by oxygen sensing include production of red blood cells (erythropoiesis) and formation of new blood vessels, fine-tuning of the immune system and fetal development. Equally important, oxygen is central to many diseases, including cancer where, the oxygen-regulated machinery is used to initiate angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) and alter metabolism to help cancer cells replicate.