Translations – Mythical Ireland speaks the Common Tongue

Nothing is lost, but is easy to lose yourself, in this fierce production of a play that looks at the value of a language

5 stars

Director Ian Rickson’s new production of Brian Fiel’s play Translations is staging at The National Theatre. Set in an 1833 hedge school in Baile Beag (English: Ballybeg), an Irish speaking community in County Donegal, the play explores the lingual boundaries that divide us and define us.

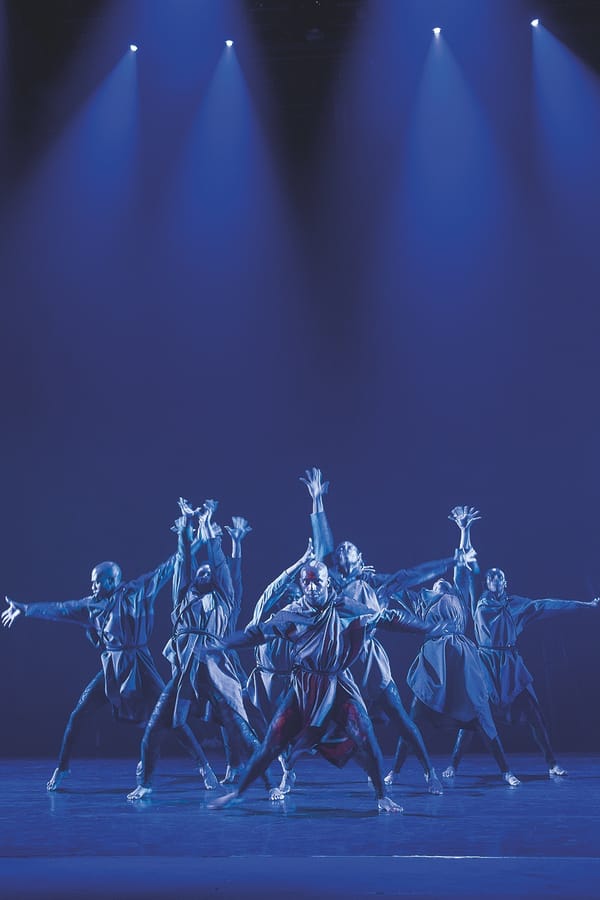

The smoky, comforting smell of burning wood greets us – a sign of what is to come. A muddy, earthen ground sprawls across a misty stage, at the centre of which is a square schoolroom littered with books. Every aspect has been carefully designed by Rae Smith and Neil Austin to create a convincing atmosphere. A girl (Liadán Dunlea) is trying to speak the simple Irish sentence: “My name is Sarah”. This is a phrase that we all take for granted, but for Sarah this sentence holds the key to unlocking one of the most valuable things in life: a connection to her kin. According to one of the hedge schoolteacher’s sons Manus (Seamus O’Hara) - it holds the key to sharing all the secrets that have thus far been inaccessible in the lonely world that is her own mind.

Translations revolves around the story of the Ordnance Survey mapping out Ireland in 1824. Lieutenant George Yolland (Jack Bardoe) is an orthographer on the mission who has fallen in love with Ireland. The Survey documents place names with Owen (Fra Fee), a native, helping George – an English outsider who is keen to learn the language. The two consider the sound, etymology, and of course history behind a name. Fiel’s play makes it apparent that in Anglicising the place names the essence of the places is lost in translation. The history of the people is embodied in the language that they speak and the names that they have chosen. Language forms a channel to the past in the same way that it forms a barrier between cultures in the present. The mountains and sea that separate England and Ireland are mirrored in the differences in language: the ‘contours’ of the cultural map.

Ciarán Hinds gives a very compelling performance as the passionate, yet often red-faced, schoolmaster Hugh who feeds his flock a diet of Latin, Greek and Arithmetic, but notably no English. In his view, it is a “plebeian” language and poets like Wordsworth who choose such a base tongue to express themselves are simply nobodies. On this point, one of the few things that could be criticised is the littering of Latin and ancient Greek throughout the script, that could be confusing for some due to the pace. However, the nudge-nudge wink-wink lusting after the fiery-eyed goddess Athene described in the verses of Jimmy Jack Cassie (Dermot Crowley) was hilarious.

Fra Fee as Owen gives an outstanding portrayal of a young man with good intentions who comes to terms with the true nature of his work translating Irish place names into English. In particular, the scenes with his brother Manus have tense, palpable undercurrents. His loyalty gradually grows and his discomfort with the task he is performing comes to a head as he passionately narrates the story behind a place whose name is simply a butchered Irish version of ‘Crossroads’, but whose history involves a strange story about a man with warts and a well - something untranslatable.

There is also a darker and more cynical side to the play. When Captain Lancey (Rufus Wright), an unforgiving English redcoat, forces the community to use the Anglicised place names, the cast effectively portray the image of a broken people. Notably, Sarah, who regresses back into her repressed, silent state. Dunlea’s portrayal of the almost mute girl is a stellar demonstration of a performance that touches us simply through body language and expression.

Language can inspire us to be who we are, but as the play and the wonderful cast and team so aptly portray, it can also be used as a tool to oppress others and take away their identity. Indeed, director Rickson realises this is not just a historical issue, and makes it known in stark fashion that history may be repeating itself in a dramatic and novel climax that leaves us thinking about oppression in modern society. All in all, a worthy play to see if you wish to see a quality cast and team put on an emotional production that will leave you thinking much more deeply about the role of language in shaping the past and the present.