Are we Headed for a New DotCom Bubble?

Marios Papadopoulos analyses the similarities and differences between the current tech market and the Dotcom Bubble of the late 90s

Above: Fig 1. Looking at around the year 1999, the NASDAQ leaped from below 3000 to the peak of 5048.62. It has taken 15 years for the NASDAQ to recover to that high. Will history repeat itself?

The entry of the new millennium was accompanied by a major stock market crash caused by a bubble known as the Dotcom bubble. The last decade of the 20th century saw the advent of the World Wide Web and the Personal Computer. These technological developments led to the creation of numerous startups, many of which had a “.com” attached at the end of their name.

Continuous investment into these companies resulted in an exponential rise of their equity valuations by the end of the 1990s. That can be easily confirmed by Figure 1, depicting the variations in the value of the technology-dominated Nasdaq index. In the span of five years, Nasdaq grew from just under 1,000 units in 1995 to 5,000 in 2000. Its peak of 5,048.62 was recorded on March 10th, 2000. Various factors are considered responsible for making the bubble finally pop, including a raise of interest rates by the US Federal Reserve along with analysts’ belief that investing in technology sector should no longer be prioritised.

By March of next year, the US economy had entered a recession. Following the tragic events of September 2001, the era of the dotcom companies officially ended, as no Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) from technology firms were filed.

Underlying Causes of the Crash

The most important question is, what were the underlying causes of the crash? The investing community’s persistence in pouring money into unprofitable Internet start-ups appears as the root of the problem. The astonishing success of firms such as Amazon and eBay led several entrepreneurs to believing that the creation of a web-based company was a path of guaranteed success, which explains the overly large number of dotcoms entering the stock market.

Aspiring wealth-creators were not the only ones captured by that belief; this sentiment governed investors’ thinking to a large degree. Consequently, they began to disregard the basic rules of investing, including analysing business plans and price to earnings ratios. Instead of focusing on how start-ups could generate revenue, analysts instead focused on irrelevant aspects of their operation and derived unrealistic models related to future cash flow.

As expected, the overabundance of capital resulted in an unreasonable number of “dotcoms” going public. In order to become successful, these companies sought to differentiate themselves from the pack through marketing. It has been reported that some devoted more than 90% of their budget to advertising! This approach was unsustainable as the majority of these firms had yet to form a sustainable business model. Even more astonishing, some had not finalised their products upon issuing their IPOs!

The combination of these tendencies constituted a recipe for disaster. What is perhaps more unfortunate is that certain voices had realised the boom could not be sustained, such as Alan Greenspan, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve. He cautioned against over-investing in the technology sector at the end of 1996. However, his choice to adopt a lax monetary policy until early 2000 was heavily criticised by multiple analysts as it only helped accelerate the formation of the Dotcom bubble. According to their thinking, a tighter monetary policy could have helped contain the situation.

Will a new bubble burst?

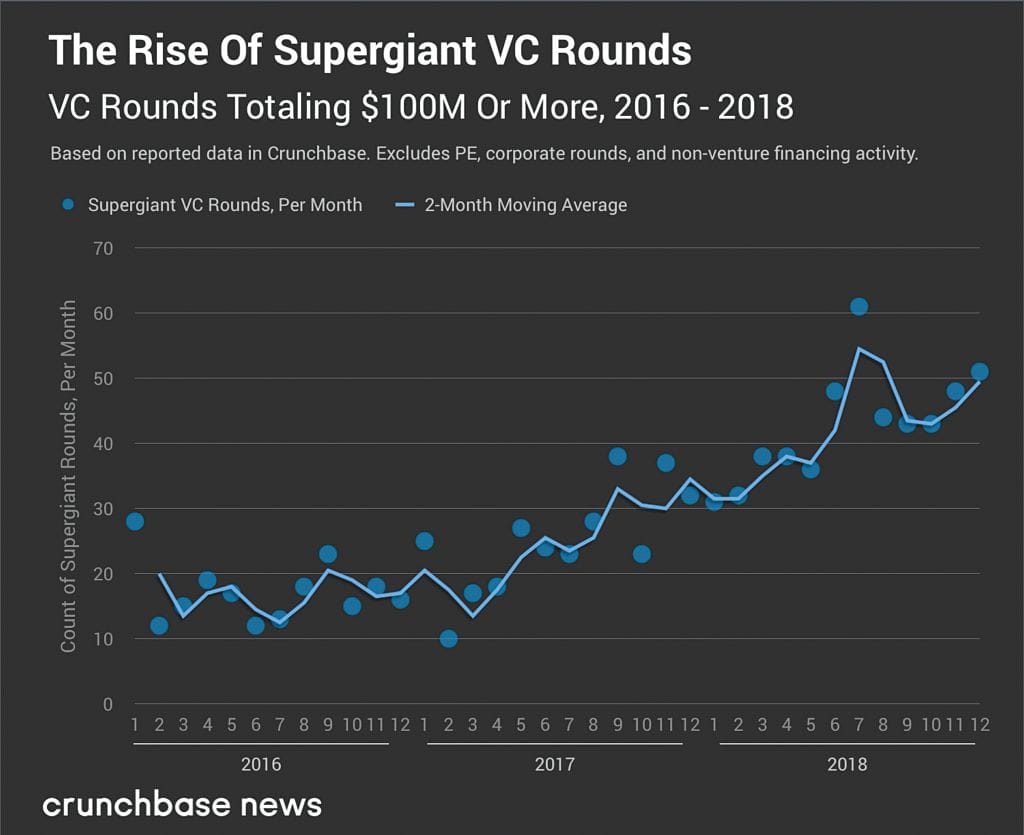

Above: Fig 2. Some companies are raising the sort of money venture capital firms raise for a single fund in a single funding round, termed Super Giant VC rounds

Many people are also wondering, will a new tech bubble burst? There are definitely signs which could be interpreted as a warning for a new Dotcom bubble. Just like in the 1990s, a large number of tech companies are going public with overly high valuations. Some of them have filed for IPOs despite the fact they have not yet been able to generate profits.

For instance, Survey Monkey, a well-known business software company, issued an IPO in August of 2018 seeking to raise close to $100.million. In the first half of the year, it recorded a net loss of $27.18 million. Similar cases include the cloud provider Dropbox and the firm DocuSign, which creates software for digitally signing documents, among others. It is also worth noting that 2018 became a record year for venture capital markets. It was the year that the largest amount of money on record was used to invest in the highest number of tech companies ever. More companies than ever before were able to raise capital in the range of hundreds of millions in a single round, as seen in Figure 2.

These developments paint a picture with several parallels to the situation established before the Dotcom crash.

However, a strong counterargument can be offered to justify why we are not headed towards a new bubble: Internet usage is growing at a staggering rate. As of January of this year, over 4.3 billion people use the Internet. To put that in perspective, the number of users was 147 million in 1999, a year before the stock market decline. It is not hard to argue that an increase in users leads to a rise in online buyers, which represents an opportunity for companies to profit. Consequently, the founding of new firms active in the technology sectors should not be surprising.

Conclusion

The stock market is notoriously difficult to predict. Currently, it appears that we are not heading for another tech bubble given the significant growth of the web’s user base. However, this does not mean that investors should not remain alert. The fundamental practice of examining profit margins, debts and sales forecasts, among other metrics, should not be ignored even if the company’s business plan appears theoretically good enough to lead to profitability. If user growth stagnates, investors without a diversified portfolio will likely be once again exposed to major losses.

As Alan Greenspan warned the investing community, it should avoid “irrational exuberance”.