How Computers Took our Music Away

Following the brief histories of jazz and rock, Felix now takes a look at the history of electronic music

Putting the history of a whole genre of music to paper is a mammoth task, especially for a genre as fluid and diverse as electronic music, so please forgive any oversight I may have made in trying to accomplish it. It is a story of technical innovation, experimentation, and of people coming together.

Laying the groundwork

Music has always been an art-form whose boundaries have been set by the tools that musicians had at their disposal. 500 years ago, medieval towns would wait for ages for troubadours to swing by to dish out some simple harmonies. In the following centuries, music played on carefully crafted instruments remained a luxury contained in swanky ballrooms, danced to by old men with powdered faces and wigs.

The explosion of popular music (music for the PEOPLE) in the 20th century coincided with the new-found mass-production of instruments, which made them affordable. This unprecedented availability of music for the people meant that instruments were no longer only a medium for routinised recitals of age-old melodies but also a platform for experimentation. The tried and tested was to be eschewed for fresher sounds, something which both the spirit of jazz, which took off long before electronic music, and atonal chamber compositions, whose composers began to rise at the turn of the 20th century, laid the foundations for.

Early experimentation with electronic music was limited to creative uses of the newly invented electric tape. This allowed for layering of instruments in a different way (now not solely by synchronous playing), controlling the speed and pitch of the sounds, and overall showed a glimpse that electronic recording of analogue sounds allowed for creation of sounds that traditional instruments couldn’t fashion. This was followed by the invention of sine-wave oscillators, modulators, filters, mixers, and a whole host of other audio manipulation equipment. Studios centred in Cologne, Tokyo, Paris, as well as the USA began to be filled by these, and the inventions eventually began to filter through to the bands of the time. Whether it was using the Theremin to add a new dimension to their sound, speeding up recordings made on tape to play with tonality (see George Martin and Strawberry fields forever), these inventions allowed for sonic experimentalism that had not been seen before. Without them, Psychedelic and Progressive rock, as well as Krautrock, would not have been possible.

But the most important invention of the 60s for the future of electronic music was the Moog modular, one of the first in a long line of synthesisers manufactured by Robert Moog. It defined the interface that synthesisers still carry to this day, and its wealth of modular sound building possibilities indirectly spawned a whole host of musical genres. Moog’s name, along with Don Buchla’s (Moog’s brother in arms in the field of modular synthesisers), forms an important part of the lore of electronic music. Creation of completely novel sounds was now at the fingertips of anyone with a synthesiser, and these were becoming cheaper and more ubiquitous by the day…

A tale of two cities

Modern electronic music has its roots deep in two cities of America’s rust belt: motor city Detroit and windy city Chicago. The mere mention of these names brings associations to a plethora of sounds, and it was the soundscapes of these two cities that proved to be the most fertile ground for a musical revolution in the 80s.

On Chicago’s side, it all started with “The Godfather of House” – Frankie Knuckles. Originally from Bronx, Frankie moved to Chicago to spin disco, soul and R&B at The Warehouse, the club which gave House music its name (because Warehouse music just doesn’t sound as cool). This is also where the beautiful story of electronic music’s connection with LGBTQ and minority communities begins - the warehouse was a safe space for what was initially a clientele of black gay men. Even though the genre came to encompass many communities, its roots will never be forgotten, and its message of equality will always proliferate.

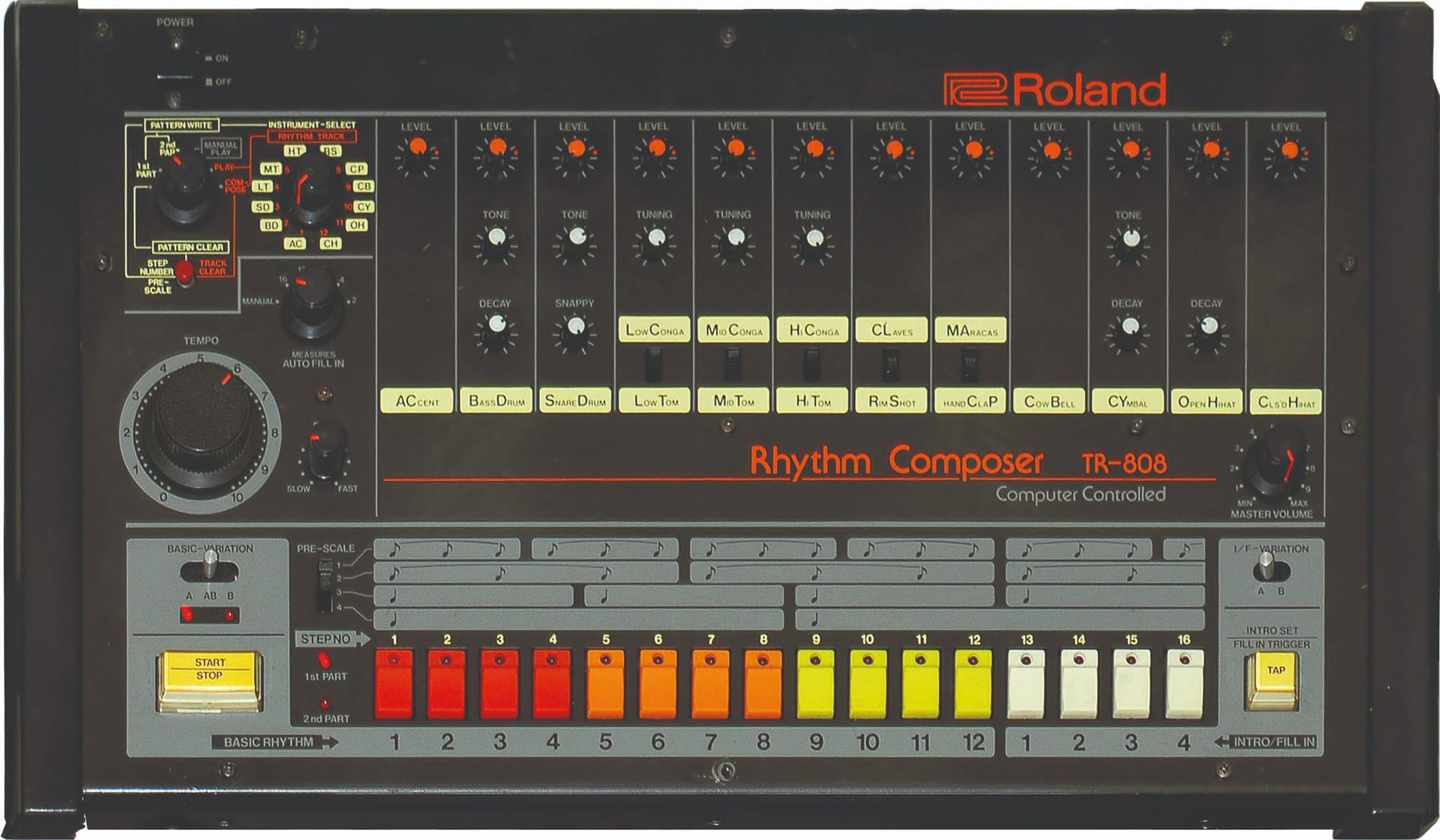

It was not just in the melodic aspect that house borrowed (or rather extensively sampled) from Disco. Disco was the soundtrack to the cocaine epidemic and the lever which lifted the ban on sexuality on the dancefloor, and it would pass on both the use of intoxicants and the emphasis on free expression through dance to its Chicago fledgling. Along with Jesse Saunders, Knuckles utilised newly commercially available drum machines in order to make disco bouncier and even more suitable for dancing. The hypnotic beat programming of the Roland TR-808 would become the rhythmic paradigm of the decade, inspiring early Hip-Hop MCs amongst others.

Jumping across lake Michigan to the border with Canada, techno was being born around the same time. It was inevitable that Detroit would be the setting for another musical explosion. Having given birth to so many great musicians just two decades prior, motor city was beginning to lose its sparkle. The motor industry was slowing down, and the hard-edged industrial surroundings, with many warehouses going empty, was the perfect place for hard-hitting tunes to be introduced to large crowds of moody youths.

Instead of taking cues from American disco, this grittier cousin of House drew inspiration from European and Japanese synthpop, and the darker reaches of funk (ergo some of the funkier early Detroit techno took on the name Electro Funk). It was three high-school friend messing around with these robotic rhythms which came to define the genre. Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson – collectively known as the Belleville Three - would go on to make some of the most important music of the decade, found labels, and inspire millions. But first the music had to cross the Atlantic.

The second summer of love

When house and techno came to the UK, they very quickly caught fire. Like the British invasion of the American rock scene twenty years prior, American sounds now conquered Britain, and offshoots of the original sounds – most prominently acid house, hardcore and rave – fuelled what became known as the second summer of love. MDMA, abandoned warehouses in late-Thatcherian Britain, fields in Somerset, and masses of youths with a point to prove started a movement which still resonates in the hearts of every diligent clubgoer today.

The mud is up to your ankles, some guy named Fred keeps telling you he loves your shirt and asking you for gum, and the soundsystem spreads like a giant, throbbing spider all around the ant-colony mass of people. There are tens of thousands of you. Maybe hundreds of thousands. Why did you drive half the way across the country to jump wildly for one night only with strangers to music which sounds like it could be the score to an alien invasion? Because this is what being human is about. Seeing other people go just as nuts as you and revelling with them in the unadulterated spontaneity of the moment. As if you were naked, you are you in your purest sense. You do it for the ecstasy.

To talk about the path of electronic music in the UK from that point on, I would need a whole new article. For the record, most noteworthy new genres over the next two decades originated here. From jungle, via DnB, garage, and finally to dubstep (almost coming full circle to a warpedly bassy version of what originally came over on the reverse techno Mayflower), the genres spawning from that first impact are both diverse and exciting.

When the curtain falls

No overview of the electronic music story would be complete without its current spiritual home. No city in the world has an electronic scene as vibrant as Berlin’s. Drawing parallels with Detroit, what allowed Berlin to become the mecca of electronic music was the post-industrial landscape following the fall of the iron curtain and German reunification. The positive energy which accompanied the fall of the wall helped propel many movements for equality and peace. And whether it was love parades or protests against needless wars - the anthem of the marching in Berlin was most likely techno. The smooth and coldly melodic sound of German electronic music is one of the most vital components of the burgeoning scene.

Getting into Berghain: is it worth it or not? Standing out in the cold for hours at a time only to be told to get lost with a simple shake of the head? Getting intimidated by the mighty shades-at-night-and-white-tuxedo-wearing, face-tattooed snake charmer that is Sven (Berghain’s inimitable head bouncer)? Nervously holding your breath as he decides whether you’re worth letting in? Many have their objections.

The key to the success of Berlin’s clubs is the atmosphere that rules inside them. It is an incredible feat that they were able to translate the German nous for perfection and efficiency into something as ephemeral as clubbing. To sum up, I’ll share what a couple who apologetically said they don’t speak German got told by some bouncers in Berlin: “Stop telling people where you’re from or who you are. Nobody gives a fuck.”

Electronic music is freedom: freedom of experimentation, freedom of expression, freedom of love. It is the apex on the mountain of proof that there is nothing as powerful in this world as music. In a world where little makes sense, music always holds the torch – may we march to the beat of four to the floor.

In the spotlight

Many will say that the best days of electronic music are now behind us, and that the world is in need of a new and exciting form of music. Even Nina Kraviz, the techno queen herself, has said that the last truly original new genre invented was dubstep, and that most of modern house and techno is made up of rehashing old sounds: nothing truly fresh has happened here since times of Chicago and Detroit.

I for one, disagree. The modern day beatmaker can be anyone, and we are currently experiencing a revolution of bedroom musicians. Lo-fi house especially has seen a whole everest of musicians flock to Youtube to flaunt their compositions over some faux-nostalgic VHS footage.

Indeed, it seems that electronic music is experiencing some form of revival. It has been popping up in mainstream culture with an air of reverence, and perhaps even a little bit of nostalgia. Good examples of this are Gaspar Noe’s film Climax, the soundtrack to which was basically a best-of album of everything from very late disco to acid house and 90s rave and breakbeat. Similarly, Saatchi Gallery, in the heart of London’s poshest neighbourhood, ran an exhibition on rave culture this past summer, which covered the second summer of love in great detail and with heartfelt sincerity.

These are examples that show that society has largely come to accept that electronic music is here to stay, and has come to appreciate the cultural significance of its roots. Besides this, the rise of superclubs and gigantic electronic music festivals has shown that there is a wider appreciation for the genre. As always, mass commoditisation of music will have its drawbacks. Some problems currently plaguing the industry are the skyrocketing DJ fees putting promoters out of business, and the rise of megaclubs offering lineups which rival festivals, which are taking away business from smaller clubs, and therefore shutting down the stages where the next big thing might have announced themselves.

With music becoming more and more accessible, and the digitalisation of the world making it incredibly facile to access content, it will be interesting to see how this affects electronic music. There will always be new sounds to explore, new formats to try, and new ways to make people dance.

One thing is for sure: the story of electronic music will only keep twisting on and on.