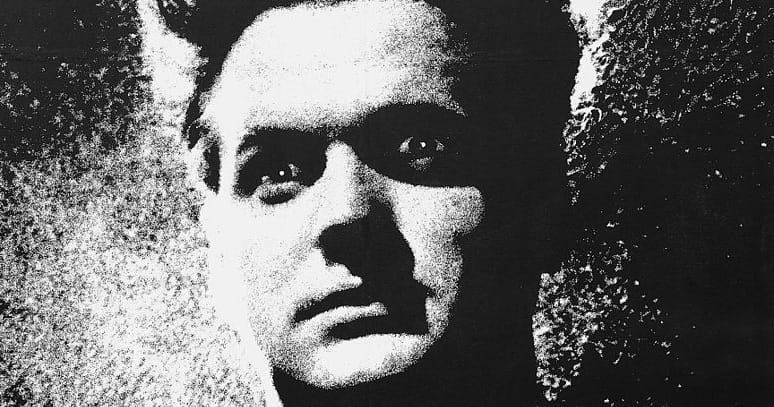

A Short Defence of Surrealism

Why should we bother with surreal film? Film editor Oliver Weir argues the case for this often misunderstood subgenre by way of the first Lynchian masterpiece: Eraserhead

Directed by: David Lynch

Year of Release: 1977

Starring: Jack Nance; Charlotte Stewart

Praises for Eraserhead are often concluded by a catalogue of asterisks. These clarifications often say something to the effect of ‘good...for an experimental movie’, or ‘good...for a surrealist piece’, or ‘good...for an abstract work’. They act as though surreal movies ought to be judged by a different criteria than ‘normal movies’. I heartily disagree. Surrealism is not some disconnected, modern invention. Producer Steven Kovács said “Surrealism was the first literary and artistic movement to become seriously associated with cinema”; it precedes Disney, the zombie genre, the Wilhelm scream, the Cannes Film Festival, and the Academy Awards themselves. Surrealism seems more modern than it is partly because it refuses to offer easy explanations. It has taken on a recalcitrant quality, never being shackled by convention or cliche, for those are the very things it so effectively dispenses of (though that is often not its primary aim). I think this is, in part, the reason for its enduring liveliness compared to all other genres, some of which are going stale. Contrary to popular opinion, surrealism is a simple extension of the artistic tradition, not something at odds with it.

"The best surreal movies will be as strange as the truths they seek to uncover, and no stranger"

All this is to say that the correct approach when going into a surreal movie is not to hold your nose. The mindset most conducive to the enjoyment of surreal cinema is that of understanding what it aims to do. Film—being only images in sequence—is but a means to approach truth tangentially. By presenting some sort of objective correlative—be it a story, a shot, or a symbol—some truth is evoked by experience, without any recourse to logic or analysis. For more obscure truths, feelings, and emotions, more obscure modes of transit are required. Do you think a movie that attempts to capture the essence of the subconscious is going to turn out like Titanic? Of course not. The best surreal movies will be as strange as the truths they seek to uncover, and no stranger.

When one ignores the context, the route up Mount Everest seems unnatural and absurd, far-removed from what we normally get up to. And yet, after years of normalisation, that route is now the obvious method for obtaining the unique exhilaration one feels at the top; it has become less absurd, and is now simply thought of as ‘the way you go to get to that place’. So stands surrealism in cinema, and the dismissal of it as strange and far-flung is true only when one neglects its context. While it doubtless aims at uncommon ends, its uncommon means are no less valid than the tactics of other genres.

David Lynch is intimately aware of these facts. He justified his casting of Jack Nance as Henry Spencer in Eraserhead by saying: “If you’re going into the netherworld, you don’t wanna go in with Chuck Heston”. In that choice there is a clear understanding of aim. Conversely, Lynch’s meticulously crafted soundtrack of clanging and crying, knocking and whistling, and his dreamlike aesthetic of shadows broken by spotlights, is not jarring just to be jarring— it is due to a clear understanding of an aim. In terms of filmmaking only, these constructions are those of a master, not an eccentric. What does one expect when the movie’s tagline reveals its aim: “A dream of dark and troubling things”? No, Lynch, like Buñuel or Jodorowsky, is as conventional as they come; he is simply an extension of a now century old tradition of using unfamiliar, but apposite, methods to capture strange and distant truths.

It may take some time to see the utility in a director’s choice. On first viewing, Eraserhead is a handful. But, on all subsequent viewings, a deeply emotional and deliberately crafted film takes shape on screen. Lynch didn’t call it his “most spiritual film” for nothing. Eraserhead, like many great surreal pictures that get neglected, is a repository for some of the most delicate themes ever depicted on screen. In order to see them, one need only find the rationale behind the madness. When that rationale is understood for what it truly is, all abstractions fall away, and what remains are those elusive truths which lie unperturbed by conventional form, only ever becoming detectable in the unreality of a dream.