Art is the Curia of all ills

Post-conclave thoughts on episcopal art

As soon as I started writing this piece, I was surprised to see the news that Pope Leo XIV has been crowned and seated in the chair of St Peter. Very few could’ve predicted the emergence of the USA’s first Pope, but as far as historical popery goes, this is by far the least surprising, scandalous or outrageous investiture. One thing that everyone knows about the Catholic church is its exquisite sense of style, panache, and artistry exemplified particularly by its leaders. In this article we will make a deep dive into the art depicting cardinals, bishops and popes throughout the centuries.

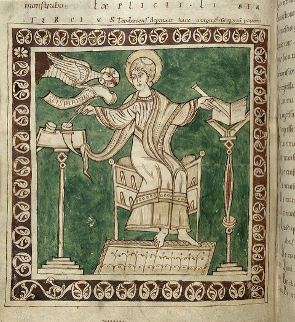

Gregory The Great

Gregory is known throughout Christian world, not only for his day-to-day work but also his work on the day-to-day, instituting the Gregorian calendar as well as kick-starting the “Gregorian Mission” of converting the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to Christianity. Here we have a piece of illuminated manuscript from the 12th century from Gregory’s Dialogues detailing the apparently ambidextrous Gregory composing said dialogues, receiving the message of the Holy Spirit, all from the comfort of his chair. This multitasking, mitre-toting figure is depicted bare-foot, symbolising his humility in his role. But for the keen eye, his posture, his outstretched arms and his bare feet are such that he is posed in the likeness of the crucified Christ; even his writing implements are exaggerated to look like nails in his hands. This miniature is chock full of religious symbolism that even a cursory glance is enough to give you a sense of not just who Greogry was as a pope, but also what the role of the Pope symbolises.

Pope Innocent X

Skip ahead a few generations and we have this portrait of Pope Innocent X painted by Velazquez. One of Velazquez’ masterpieces, he was commissioned to paint Innocent during a visit to Rome. Here, Velazquez paints the Pope as a man of serious intent, papal Bull in hand, stern look, and impressive linen mozzetta (clearly indicating that it may have been particularly warm when this portrait was commissioned). By this point in history, the actions of Popes Urban II and Innocent III had solidified papal supremacy in the western world; Innocent X sat in full papal regalia exemplifies this wonderfully, and upon completion of the portrait he was said to have exclaimed “It’s too true!”. Whether this legend is true or not, it certainly bolsters Velazquez’ reputation as a master of portraiture.

Cardinal Richelieu

This master work by French artist Philippe de Champaigne is a departure from the usual norms of episcopal portraits. Conventionally, religious figures are always depicted seated in their episcopal chairs as a sign of their religious authority. Here, the titanic figure of Cardinal Richelieu is shown standing, and it’s worth noting that famously Richelieu was not only a religious figure, but a shrewd diplomat and statesman (as shown negatively in Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers); figures of state were often portrayed in a standing position rather than seated. This dual life of the cardinal statesman is further exemplified by the cardinal’s lose red robes, revealing his blue medal of state. It may be a coincidence, but one can always identify a portrait by Champaigne by his use of both red and blue in clothing, showing his mastery in the use of contrasting colour to give his subjects depth and character. Richelieu here is also depicted holding his biretta in his right hand while offering an open outstretched left hand, indicating his dedication to religious practice, but offering his other hand as a sign of diplomatic openness.

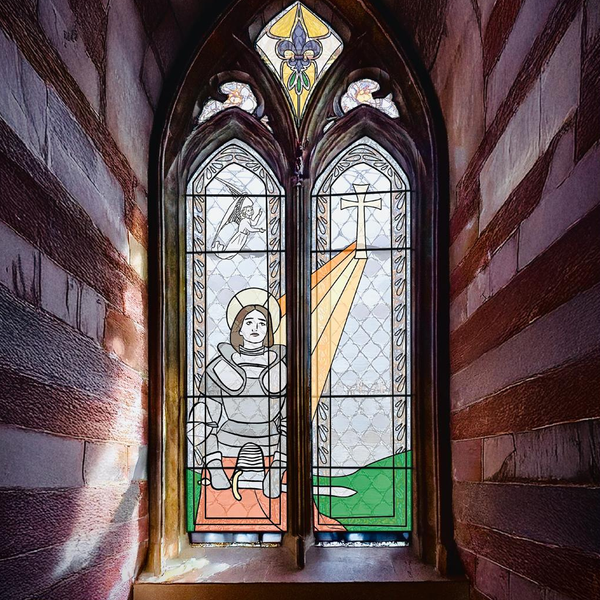

Cardinal St. J. H. Newman

This fabulous portrait by Millais depicts the figure of Cardinal Newman, one of the fathers of both Anglo-Catholicism and the Catholic Restoration of the UK. Despite his legendary work in the restoration of traditional practices to the British Isles, this portrait seems quite bare in comparison, but only a cursory glace at this portrait gives one a sense of paternalism and tranquillity. Millais was one of the members of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and his use of colour is exemplary, choosing to depict the cardinal in a profound shade of red, with extraordinary detailing in the fabric work. In contrast to Velazquez’ stern portrayal of Pope Innocent X, here we see the peaceful cardinal sat directly in front of us, staring at the viewer with wisdom in his facial features. It is little surprise that Newman is also known for his tracts and poems, particularly his magnum opus The Dream of Gerontius, and his eyes convey that sense of poeticism to the viewer, rather than overwhelming us with religious authority or stately presence.

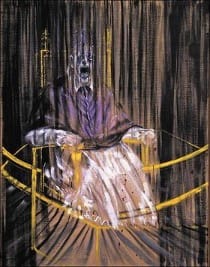

Pope Innocent X (again)

Bacon is known for his studies into the masochistic and grotesque side of the human form, and in true Bacon fashion it is once again filled with symbolism. The heavy brush strokes across the portrait resemble a set of satin curtains, obscuring the screaming, disfigured pope from the viewer. This curtain effect emphasises the figures isolation from the viewer while Bacon himself said that the meaning of the portrait “slides slowly and gently across”. This idea of isolation is modified by the transformation of the papal see into a golden cage, turning isolation into entrapment within gold bars; despite the pope’s evident status, his place in society is separate and elevated to the point of isolation. The haunting scream coming from the skeletal pope is just the cherry on top for this exercise in existentialism.