Attenborough visits Imperial

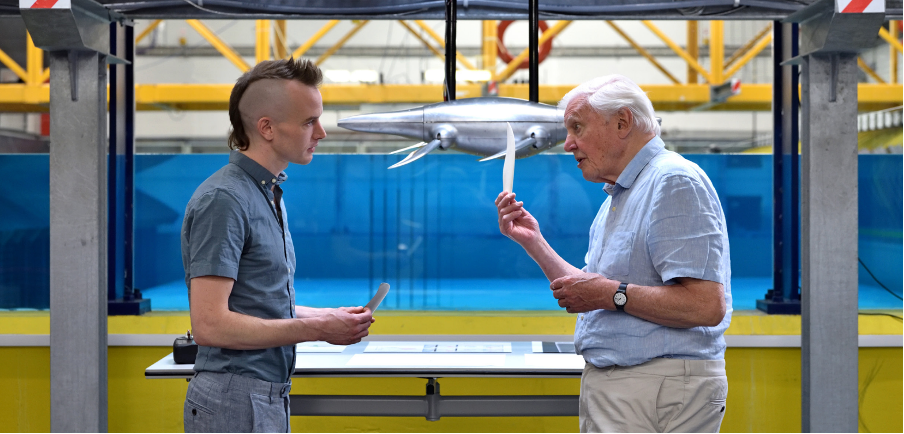

Sir David Attenborough visited Imperial last month to film Dr Luke Muscutt’s robot plesiosaur, Flip.

Legendary documentary maker Sir David Attenborough paid a visit to Imperial’s South Kensington campus in December, to film for his new programme, Attenborough and the Giant Sea Monster.

Released on New Year’s Day, the documentary follows Attenborough as he investigates the discovery of a giant skull in the cliffs of Dorset. The skull is revealed to belong to a pliosaur, a reptile that was the length of a London bus, and was alive during the Mesozoic Era.

In the documentary, Attenborough visits Imperial to understand how the pliosaur would have achieved the high speeds necessary to catch its prey, given its large size.

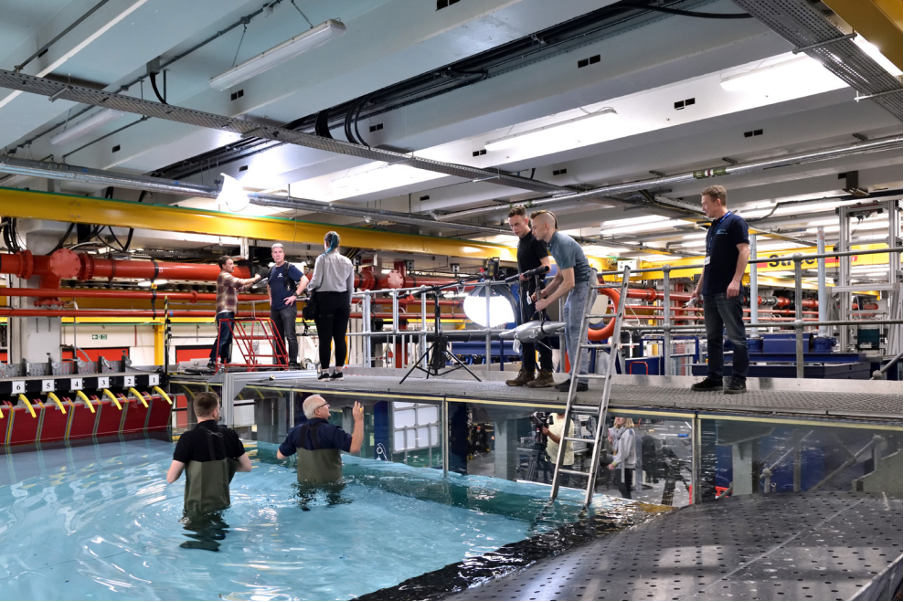

He speaks to Dr Luke Muscutt, a technician and aerospace engineering graduate working at Imperial’s Hydrodynamics Lab – one of the UK’s largest state-of-the-art wave tanks.

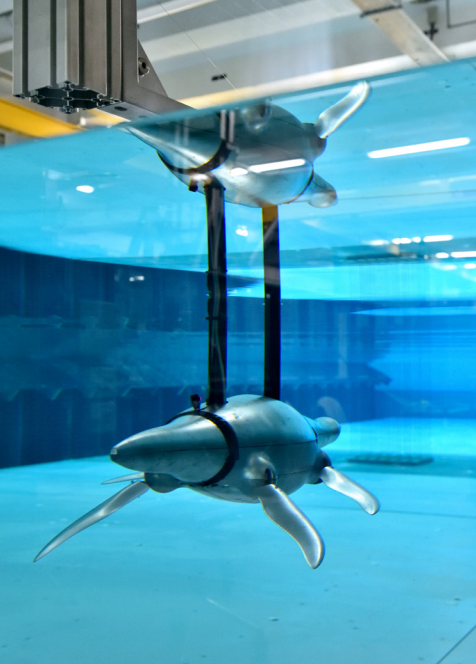

Dr Muscutt built a remote-controlled, free-swimming robotic plesiosaur named Flip. He wanted to study how plesiosaurs – the group of marine reptiles to which the pliosaur belonged – used their four large flippers to generate thrust.

Muscutt guides Attenborough as he pilots Flip, the robotic plesiosaur, through Imperial’s wave tank.

“The fossils of the pliosaur show that the flippers were very much like wings,” he tells Attenborough. He says that the two hind flippers can operate at a much higher thrust and efficiency by utilising the wake of the two front flippers. “We see a similar effect in the flight of migrating birds such as geese.”

Geese fly in a V-shaped formation, in which each bird uses the uplift created by the one in front of it.

“You can think of the pliosaur as almost two birds, one flying behind the other,” explains Muscutt. “The hind flipper has increases in thrust and efficiency of up to 40%. This would have increased the swimming speed that pliosaurs would be able to achieve, and increased the number of different things it could eat.”

Estimates suggest the plesiosaur could reach speeds of up to 30mph, which, says Attenborough, would make it “one of the fastest animals in the Jurassic seas”.

Learn more about Muscutt’s robotic pliosaur and how it was filmed in Imperial’s wave tank here.