Babyferatu

The feral girl’s Barbenheimer

In light of the frenzy of summer 2023, when two of the year’s biggest films Barbie and Oppenheimer shared the same release date, Hollywood marketing executives have been trying – unsuccessfully – to recreate the magic. Barbenheimer, as it was coined, encouraged cinema goers to watch both films, tonally far apart from one another, in the same day. Audiences leaned into the experience by dressing on theme, in pink for Barbie and black for Oppenheimer, transforming a cinema outing into an event. This inspired memes and Halloween costumes, cementing Barbenheimer into a cultural phenomenon.

More recently, Gladiator 2 and the Wicked movie, which also shared a release date, tried to make “Glicked” happen. By all other measures, it should have been the next Barbenheimer. Both films were highly anticipated, featuring an all-star cast and massive fanbases, yet they were burdened by their own legacies. Wicked, an adaptation of the beloved musical, faced the impossible task of satisfying an already devoted and obsessive fanbase; meanwhile, a sequel to the hugely successful 2000 film, Gladiator 2 struggled under the enormity of its predecessor. When a film attempts to reinterpret something deeply nostalgic, it risks tarnishing memories – and you cannot compete with nostalgia. Although both films were received fairly well it made it hard for the films to stand alone, and even harder for the two to be made into an item. Also, by this point, people had caught on to tactics used by the media and have grown weary of them.

Now, sadly, we might never witness another Barbenheimer. All subsequent marketing campaigns lack the novelty and juxtaposition that made it so special. Yet the beauty of these insane cultural shifts lies in their ability to create ripples in the corners of the internet that pay homage to them. So, for all the girls (and everyone else) who are weird, off-putting, and carry within them an indescribable darkness, may I propose: Babyferatu.

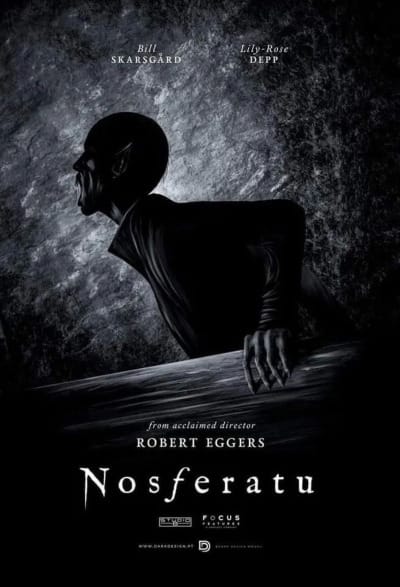

An internet-coined mashup of the movies Nosferatu and Babygirl, Babyferatu differs from Glicked or Barbenheimer in that its movies don’t share a release date, with Nosferatu being released on Christmas Day last year and Babygirl on 10th January this year, making the pairing seem less PR driven and more organic. Still, in keeping with the Barbenheimer formula, both films boast A-list casts and vastly different plots, set in completely different time periods.

What sets Babyferatu apart, however, are the thematic threads that are best appreciated when watching both films back-to-back. In their own ways, the films explore darkness and control, with leading ladies who undeniably command attention as the most interesting characters in their respective stories. And, perhaps most importantly, both films are undeniably horny.

Nosferatu: The irresistible allure of an ugly guy

Nosferatu, directed by Robert Eggers and starring Lily-Rose Depp and Nicolas Hoult, is a retelling of the 1922 German silent film of the same name. The original Nosferatu was itself an unauthorised adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, with the character’s names changed in an almost identical in plot.

The film is set in 1800s Germany and tells a tale of twisted obsession between Ellen (Depp) and vampire Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) who has been plaguing her dreams since childhood. After Ellen marries Thomas (Hoult) she feels freed from her past melancholy but like a vengeful ex, Count Orlok sets into motion a plan to reclaim her. With the aid of his faithful servant and Thomas’ boss Knock, Orlok lures Thomas to his home in Transylvania where he witnesses terrifying and otherworldly events, narrowly managing to escape. Orlok, now on his way to Germany, brings with him a plague that begins ravaging the town. As the world around her descends into chaos, Ellen, tormented by her visions of Orlok, finds herself drawn to him despite her love for Thomas. Her internal struggle becomes the emotional crux of the film as she wrestles with her fate and the darkness within her.

The films explore darkness and control. And, perhaps most importantly, they are undeniably horny

The performances in Nosferatu are stellar across the board, with each actor bringing depth and complexity to their roles. Depp is particularly impressive as Ellen, capturing the torment and vulnerability of a troubled young woman haunted by forces beyond her control. Skarsgård plays the Count as a grotesque, towering, corpse-like figure with a growling voice that adds an eerie layer of menace. The film’s horror and gore are masterfully executed, with several scenes achieving the intended unsettling effect. One scene involves a gypsy ritual, in which a virgin girl on horseback is used to locate and destroy a vampire’s grave. This scene is steeped in folklore, which believes that a virgin would refuse to step on a vampire’s grave, helping villagers to identify it. The sequence is chilling and ties the supernatural elements to regional mythology, adding a layer of authenticity to the film.

Knock, a character reminiscent of Renfield from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, is particularly memorable. As Orlok’s devoted servant, he is both grotesque and pitiful. The film leans into this, with the moment he bites the head off a live pigeon being one of the most rancid and visceral scenes in recent memory. The audible gasp from the theatre during this scene is a testament to its shocking realism.

However, there are moments where the film succumbs to familiar horror tropes. For instance, Thomas repeatedly pries into Orlok’s secrets, questioning the gypsy rituals, despite clear signs that something sinister is afoot. His failure to flee the castle after multiple nights of eerie occurrences and finding bite marks on his body feels frustratingly typical of the genre, pulling the viewer out of the otherwise immersive story.

One of the standout performances comes from Willem Dafoe, who plays Professor Von Franz, a Van Helsing-like reclusive doctor and expert in the occult. Dafoe’s ability to embody any role he plays shines through; his tenderness and empathy towards Ellen are particularly moving, bringing a sense of warmth and hope to the cold, foreboding atmosphere of the film, and helping to ground the film amidst its more supernatural elements.

What stands out most about Nosferatu is its seamless integration of traditional vampire folklore, Bram Stoker’s original Dracula, and the 1922 silent film Nosferatu. The film pays homage to these works while carving out its own identity, allowing it to feel fresh and exciting. By drawing on familiar elements of the Dracula story, the audience is anchored within the narrative, enabling new twists and imaginings to shine. The relative obscurity of the original Nosferatu also works in the film’s favour, as it avoids being overshadowed by its predecessor. Ultimately, this film is an impactful, visually striking tribute to the enduring appeal of the vampire mythos.

Babygirl: desire, shame, and a glass of milk

While Nosferatu succeeds because it takes its genre and source material seriously, the triumph of Babygirl lies in its ability to acknowledge how ridiculous it can be. This levity and humour provide respite from the tension pervasive throughout the film, while also providing a stark contrast when the high stakes of power abuse and infidelity is bought into play.

Directed by Halina Reijn, Babygirl is centred around Romy (Nicole Kidman), a high-powered CEO in New York with two children and a loving husband of 19 years (Anthony Banderas). Her seemingly fulfilling life takes a turn when she begins an intense affair with a younger intern, Samuel, played by Harris Dickinson. As their relationship deepens, boundaries blur and lies multiply, threatening to unravel the carefully constructed world Romy has built for herself.

The nature of Romy and Samuel’s relationship has strong dominant-submissive undertones, enhanced by the thrill that Samuel could make one phone call and end her whole career. In the real world, Romy has all the power and control but, in the words of Samuel, “I think you like being told what to do.” Not too much of Romy’s backstory is revealed, but the few details that she lets slip are crucial to understanding her character. She grew up in a cult during the 1970s, an era of free-love and liberation; thus her role as CEO of a robotics firm specialising in warehouse automation seems like an act of rebellion. She is no longer a follower, but a leader. Striking shots of her warehouse filled with robots placing items into boxes act as a metaphor for Romy’s life until she meets Samuel. Each aspect fits into its own box: her job, her children, her husband, and her sex life. Perhaps, though, it is this repression of her past, where she grew up following orders and being told what to do, that spills over into her fantasies, setting the stage for her relationship with Samuel.

Samuel is also cloaked in mystery. He is introduced to Romy and the audience on the streets of New York, where he calms down a rabid dog that would otherwise have attacked Romy. From the jump, he is in control. On the surface, he seems to have had a normal upbringing. His parents were divorced, but he seemed to have a stable relationship with both, regularly travelling up to Ohio to visit his father, a philosophy teacher. Yet, like Romy, Samuel harbours a shameful side to himself that is finally given space to breathe in their relationship. This darkness, this compulsion to conquer goes against the charm and nonchalance he projects to others. Both characters find solace in being able to share their truth with another. Romy needs what Samuel has to offer, and vice versa. In this way, an intoxicating connection is formed.

Babygirl succeeds in many aspects, particularly in its nuanced portrayal of relationships. Romy and her husband Jacob have an extremely loving and fulfilling bond. They support each other professionally, parent collaboratively, and retain this deep affection and understanding for each other even after all these years. Also, Anthony Banderas is a sexy man! This film doesn’t lean on the trope of an unattractive and negligent spouse to justify the cheating. The fatal crack in their relationship stems from Romy’s inability to communicate her desires. She is so ashamed of herself, of being judged by the man who loves her the most that she inadvertently drives herself into the arms of another. This discomfort is so effectively conveyed by Kidman in a scene where Romy physically hides under her duvet before telling Jacob about her sexual desires. She speaks so quietly – yet even after Jacob listens, and is receptive to what she wants, Romy backtracks and takes her anger out on him.

Although Babygirl is marketed as an erotic thriller, at times it carries a misplaced feel of a horror movie. The tone occasionally veers into a darker, foreboding territory that doesn’t entirely align with the film’s themes or storytelling. This is particularly noticeable in the soundtrack, which often feels overly ominous and out of step with the scenes it accompanies. Yet despite these tonal inconsistencies, the fallout and eventual reconciliation between Romy and Jacob is handled with nuance even though the film does stops short of grappling with the gravity of Romy’s abuse of power. While it’s shown that both Romy and Samuel misused their positions in some way, the fact remains that Romy was Samuel’s boss, a grave imbalance of power that demands more exploration than what is offered.

She is so ashamed of herself, of being judged by the man who loves her the most that she inadvertently drives herself into the arms of another

Overall, Babygirl serves as a gripping exploration of sexual dynamics and female desire. It is undeniably directed by a woman and while it lacked the satisfaction of justice for Romy’s abuse of power, perhaps that is the most realistic aspect of the film. Romy faces no consequences because she is wealthy and powerful, while Samuel leaves the company and fades into obscurity. He is but a blip, a fleeting vessel used to bring Romy and her husband closer together. To me, that is the most brutal part. While both people’s lives are changed, the more lasting impact is on Samuel; he is younger and poorer. It’s a bleak but fitting conclusion to a movie centred on control and power.

Nosferatu and Babygirl are dark, provocative films that explore complex portrayals of women, embracing their flaws and moral ambiguity. They present female characters who are strong yet morally murky – Ellen cheats on her husband, and Romy seduces her intern – but their actions are portrayed with a leniency that is almost exclusively offered to men. Both delve into themes of power and control, with characters whose inherent darkness is left unexplained. While Willem Dafoe and Harris Dickinson deliver standout performances in their respective roles, their male characters serve as secondary figures, putting the spotlight on stories that centre women. Together, Babyferatu is a compelling double feature that reflects on female agency and desire in ways that feel fresh and subversive.