Changing horizons: where STEM meets languages

Trends in language learning at Imperial (and beyond).

Mathematics is known as the language of science – and Imperial has a reputable department to explore that – but who’s in charge of the science of languages? Enter the Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication. Their flagship Horizons program allows undergraduates to discover and practise languages, in addition to a breadth of other humanities and soft skills classes.

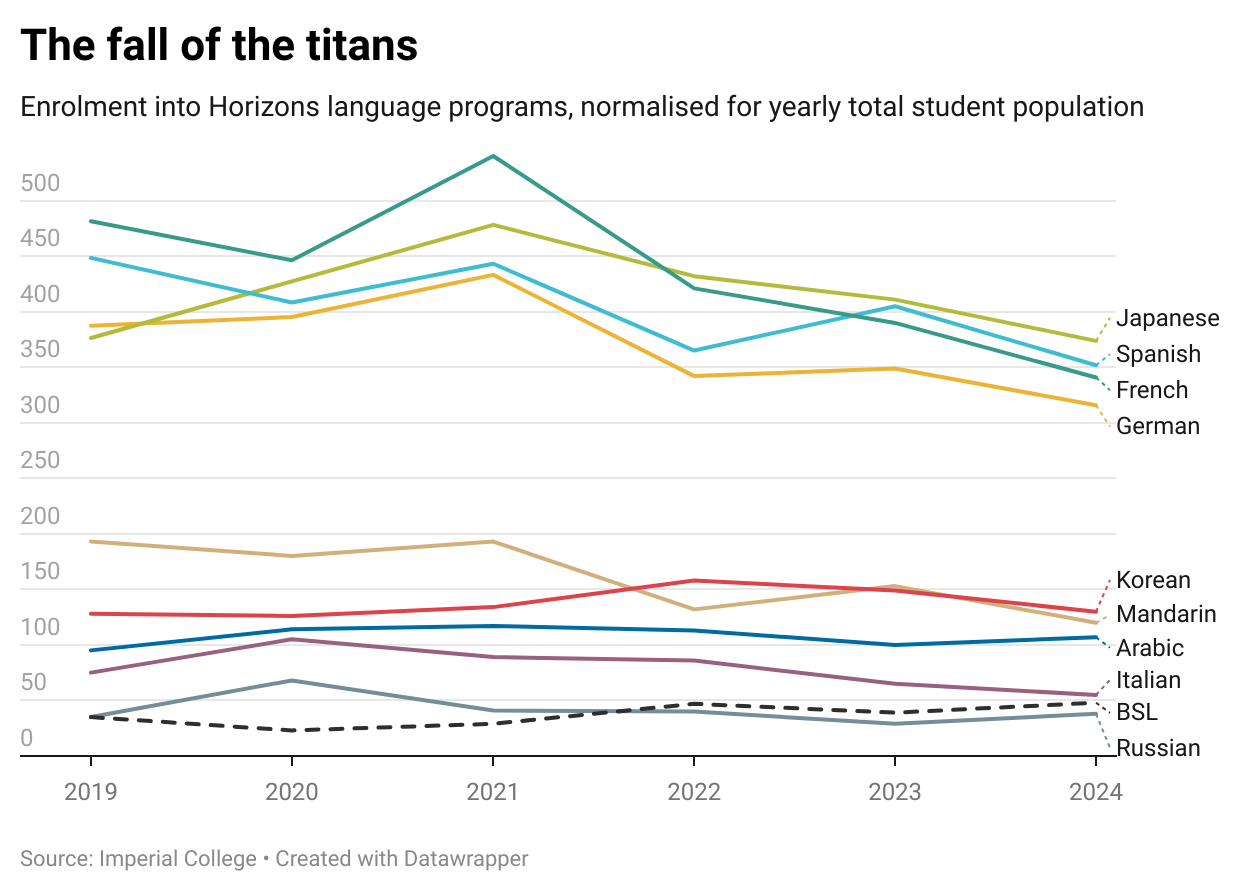

Imperial is well-known among STEM universities for its commitment to language teaching, yet the enrolment data obtained by Felix reveals changing dynamics (see graph). In spite of high enrolment in absolute terms – which have hovered around 2000 students in the past few years – the numbers peaked in 2021, as the Covid pandemic subsided. French, Japanese, Spanish and German – by far the most popular languages, representing among them 74% of all registrations over the past 6 years – have faced a steeper decline than less demanded languages like Arabic or Russian. By contrast, British Sign Language (BSL) has steadily gained in popularity since its introduction a few years, albeit from a low base. Doctor Iria Gonzalez-Becerra, Languages Field Leader and Senior Teaching Fellow at Imperial Horizons, says the course is especially popular among medical students, and hopes they will be able to expand its reach.

What factors in the language choice of CV-oriented Imperial students? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the popularly a language broadly aligns with the size of the population that speaks it globally and its economic output. There are outliers: Mandarin, despite being spoken by more than a billion people which produce roughly a quarter of the world’s wealth (depending on the precise metric considered) was studied this year by less undergraduates than Korean. Doctor Gonzalez-Becerra notes that cultural affinities are a major determiner in one’s language choice.

Outside of Imperial, academic language learning is also taking a toll. Speaking at a panel hosted by the delegation of the European Union to the United Kingdom earlier this month, Bernadette Holmes (MBE) lamented the steep decline in language electives since they were made optional by the government. Ms Holmes considers the traditionalist approach to languages – with a disproportionate emphasis on the “Big Three” languages that are French, German and Spanish – as out-of-touch with the current demographics of the country, as many young British pupils with a non-European immigrant background might be more motivated to reconnect with their heritage languages instead.

This might also explain why these lacklustre numbers are in such contrast with the dashing rise of language apps like Duolingo in the UK, which offer a much greater diversity of dialects. In the discussion that followed that panel, I overhead an old joke that still rings true, “Bilingualism is like day-drinking: it’s classy if you’re rich, but trashy if you’re poor”. As highlighted by Ms Holmes, a shift in the perception of multilingualism is also in order: street-bound diglossia should not be a source of fear but be recognised for its potential contributions to individual adaptability and professional opportunities.

Yet from an employment perspective, the use of foreign languages for native English speakers is debatable. Today, English the world’s hypercentral language, as coined by Dutch sociologist Abram de Swaan – it is steadily dislodging other global languages from their historical niches, such as French in the North African business sector – and it might be the single most useful professional skill for non-native speakers. On the other hand, for a British student with no particular desire to live or work abroad, Python might be the most economically valuable language to learn. The rise of AI-based translators, which now rival diplomatic and professional translators in terms of accuracy and style, will further damage the attractivity of languages.

“If you consider [language] education as a means to a unique end, which is get a job,” agrees Doctor Gonzalez-Becerra, “it has a low return on investment” for neophytes. She notes the discrepancy between employers’ claims to seek multilingual candidates, and the reality of the skills that make the difference during interviews. Therefore, the true motivation to start a new language should come from the enjoyment one gets from it: “For me, that’s a sufficient justification, and actually that is the correct justification”. Furthermore, a knowledge of multiple languages has well-established benefits on cognition, and remains perhaps the only way to bridge the gap between the cross-cultural “us” and “them”.

Although picture is bleak on a greater scale, Imperial is making sure students can give their grey matter some exercise and impress their friends by ordering their takeaway noodles in Mandarin (homophonous orders might sometimes arrive, which spices up the dinner). “If you think about it, Imperial actually is investing heavily in languages because our languages classes only have around 20 students,” points out Doctor Gonzalez-Becerra, who reminds me of my 6-student-strong Russian course. But I need no convincing; I wouldn’t be an Imperial student had I skipped my English as a Foreign Language class, and I most certainly would not have had the pleasure of writing for Felix.