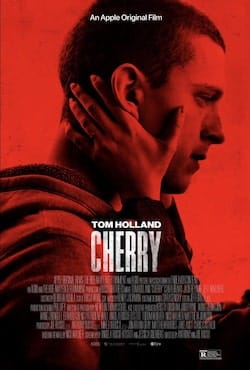

Cherry - The Russo brothers' super flop ★★☆☆☆

'Cherry'—led by Tom Holland in his most demanding role—recounts five tumultuous years in a young man's life, whether it's young love or crippling addiction, prison life or the brutality of war. 'Cherry' has so far divided audiences with its showy (and often irregular) visual style. Film Editor Oliver Weir reviews this latest feature from the Russo brothers, which is streaming on Apple TV+ now.

After delighting in the scope of the possibilities afforded to them by Jeff Groth and Newton Thomas Sigel (both in editing and cinematography respectively), the Russo brothers should’ve then whittled down their options and selected one (possibly unique) style for Cherry. What they did instead was pick all of them. Every card they could play, they did play. Throughout Cherry, I wavered between the opinion that these choices were bold, inventive, and necessary, to thinking that the whole diverse display was some form of penitence; penitence for the guilt they felt after Martin Scorcese said that superhero films—many of which are directed by the Russo brothers—were “not cinema”, instead likening them much more to “theme parks”. Consequently, many scenes in Cherry felt like poorly directed attempts at ‘high-art’. The disappointing thing for the Russo brothers is that highly stylised and often pointless subtitling of dialogue, as well as showy cuts and haphazard background fades, does not constitute the ‘high art’ they clearly think they’re capable of. This disjointed vision—which many people have not hesitated to call a failure—is the first critical flaw of Cherry. I thoroughly enjoyed the style of the first few chapters and, having seen the film’s aesthetic lauded by the American Society of Cinematographers, I was hoping that the slick transitions and quirky imbalances of light and colour would persist for the rest of the film. However, that initial style was abruptly thrown to the wayside as the drama shifted from America to Iraq. The issue with this is not so much to do with what replaced the initial style, as many have argued, but more to do with the amateurish disunion between the styles. One could certainly imagine a different visual style for each stage of Cherry’s life, where the transitions are smooth and considered and each provides its own nuanced contribution to a cohesive whole; this is, unfortunately, not what happens in the real thing. I would wager, therefore, that the visual hodgepodge is a consequence of either a genuinely poor (directorial) sense of what works together, chapter to chapter, or, as many have concluded, that no attempt was actually made to unify styles in the name of creating a truly unique and complex whole, and that it was, instead, an empty exercise in style, born from resentment, intended to pardon the Russo’s from indictments against their artistic rigour.

the vastness of the subject matter is daring to the point of stupidity

The second critical flaw with Cherry is the bulkiness of its plot. The vastness of the subject matter is daring to the point of stupidity. In 2 hours 20 minutes Cherry attempts to portray: teenage isolation, adolescent mischief, a first romance, a first breakup, the harshness of a military boot camp, the difficulties of long-term relationships, the brutality of war, the loss of a friend, the joy of reuniting with a loved one, the struggle of finding a job, the soul-crushing effects of PTSD, the powerlessness of a heroin addiction, the effects drug addiction can have on your loved ones, the potential for an overdose, going into rehab, coming out of rehab, mob bosses, bank robberies, prison life, getting out of prison, reuniting again, and so on and so on. This, you may have gathered, is a bit much; or at least too much to cover with the nuance that each of these complicated issues deserves (and all within something that isn’t 9 hours long). No audience member who has gone through any one of those moments in any depth is going to be able to relate to a watered-down, 10 minute cameo appearance of their experience. Once again, it seems as though the Russo brothers looked at the source material and, with the knowledge that they ought to slim the plot down and focus accordingly, just ended up doing it all.

no amount of fake, stick-on moustache can ever convince me that baby-faced Tom Holland commands the prison yard

The third critical issue with Cherry is one of casting. Ultimately, endeavouring to make a film of this scope, and with the sensitivity one would want, is entirely futile. It never ends well unless you’re Béla Tarr or Ingmar Bergman. However, if you’re intent on trying, you should at least go down nobly. In order to capture young love, the brutality of war, and the ruthlessness of drug addiction, all with one net, you need to cast someone who has both limitless range and someone who can convey the nuance of each new environment with the depth of a fractal, regardless of the time, emotion, or circumstance. It’s no insult to say that Tom Holland is not up to the task—nobody is, it’s a poor screenplay after all. Holland seems right at home at the beginning of the movie—in which both his real-life personality and his experience from other roles support him splendidly; however, as the movie changes scenery and subject matter, he appears completely out of his depth, especially during the film’s ‘exploration’ of addiction. Holland, it seems, was a safe pick, not a wise one. No amount of fake, stick-on moustache can ever convince me that baby-faced Tom Holland commands the prison yard.

Interestingly, Cherry slips very easily into that list of films that are perfectly summarised and reviewed by a line of dialogue they themselves include: “It's as if all of this were built on nothing, and nothing were holding all this together”. With this sigh of exasperation, I lost all sense of time with Cherry, and not in a good way. After the needless prison sequence I completely expected the Russo brothers to do the full-monty and crack on with portraying old-age (presumably by leaving Tom Holland out in the sun for two months to let him wrinkle, or by giving him a bushier moustache). But, thankfully, it was not to be. I was instead relieved when I saw that they were wrapping up the movie, having let Cherry age 5 years in the space of 2 hours—God knows I could relate to that.