Clicks over conscience: Rage bait may come back to bite brands

Rage bait is not new to the marketer’s toolkit, but flirting with culture wars risks chasing short-term engagement over long-term success.

We’ve all seen Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle ad campaign. You know the one I’m talking about – Sydney Sweeney, the blond-haired, blue-eyed actress with the great “jeans” that are “passed down from parents to offspring”?

The campaign in question caused a social media uproar this July just after its launch, with one side of the battle claiming that the company was playing into the racist concept of eugenics (an ideology which often regarded white people as the genetically superior race), and the other side voicing its annoyance with the “over-sensitive” Gen-Z audience.

Regardless of any negative reactions, the company certainly succeeded at gaining attention. Having faced sluggish sales in the first quarter, the following quarter saw American Eagle draw in over 700,000 new customers in the US and beat sales expectations. By the end of August, its stock was up 13% year-to-date. Executives credited the campaign as a key driver. “Every single marketing metric that I look at is flashing a green light, and we’re only six weeks in,” Chief Marketing Officer Craig Brommers told Marketing Brew last month.

Whilst this may seem positive at first glance, the campaign raises bigger questions about modern marketing strategies and ethics.

Rage bait or honest mistake?

American Eagle responded to the social media storm by rebuking the idea that it was intentionally provoking its audience, instead claiming that the ad was intended to “spark a conversation about optimism, confidence, and self-expression.” Its CEO told the Wall Street Journal, “We stand by what we did,” and that they “never would’ve done it” if they felt it played into racist ideologies.

Many find this unconvincing. After all, the concept of “rage baiting” in advertising is not new. Whether we label it as “shock advertising” or the “confrontation effect,” the concept is the same – advertisers know that if their content generates a strong, negative emotional response, they will be rewarded by a flurry of comments, media coverage, and ultimately coveted brand visibility.

Dr. Omar Merlo, Associate Professor of Marketing Strategy at Imperial Business School, notes that marketers have long known that controversy can be one of the quickest ways to boost awareness in the short term. In an age where companies compete for clicks amidst emotionally-wired social media algorithms, it isn’t hard to imagine marketing teams intentionally capitalising on outrage.

Merlo believes that a company’s reaction to backlash following a campaign can give us clues as to whether it was all part of the plan. “Often, how companies deal with it tends to be proportionate to how well thought-out the action was in the first place,” he says. “If you find companies sticking to their guns, it’s because they put a lot of effort and thought into it before doing it.”

American Eagle’s doubling-down on its campaign contrasts the actions taken by e.l.f., a makeup brand that recently came under fire for featuring comedian Matt Rife in its campaign. Consumers took issue with the brand’s choice of Rife, a comedian notorious for making jokes about domestic violence, especially given its outward commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) and “doing the right thing.” e.l.f. issued an apology following the backlash, stating “We understand we missed the mark with people we care about in our e.l.f. Community.”

Ill-thought-out ads can fall through the cracks for a number of reasons, but Dr. Poornima Luthra, Imperial senior faculty and author of multiple books on DEI, thinks there is no excuse for falling short in 2025.

Luthra says a lack of diversity in marketing teams or inadequate market research may be to blame: “If [American Eagle] didn’t think that having G-E-N-E-S cancelled out and replaced by J-E-A-N-S wouldn’t raise the eugenics topic of discussion, then they weren’t listening, or they didn’t do enough market research, or they didn’t test the campaign across generations.”

“If decision-makers are living in an echo chamber where they believe that their viewpoint is the predominant viewpoint, without really getting a good enough pulse on the market, I do think that they might be surprised at the backlash,” she says.

Might this explain the ad that Dunkin’ Donuts released only six days after the Sweeney campaign’s launch? In a campaign titled “The King of Summer,” The Summer I Turned Pretty star Gavin Castalegno attributes his golden tan to none other than his “genetics.” (What does this have to do with donuts again?) Or was this an attempt to piggyback on American Eagle’s viral moment?

Short-term gain, long-term pain

Whilst the long-term impact of the Sweeney campaign remains to be seen, many marketing professionals believe that controversial ad campaigns risk damaging brand loyalty and trust after the mania dies down. Stephen Waddington, Media Advisor at Wadds Inc. and author of Brand Vandals says “The short-term impact may deliver a spike in attention, search, and social mentions. It may even lead to sales. But long-term is almost always an erosion of trust.” Regardless of what was behind a campaign, Waddington argues “the intent matters less than the outcome. If people feel mocked, excluded, or manipulated, the brand or organisation pays.”

Merlo explains that a disproportionate focus on awareness in the short-term can undermine a brand’s attempts to build positive associations in the long-term. Both visibility and the story or values that a brand embodies are essential for determining overall brand equity.

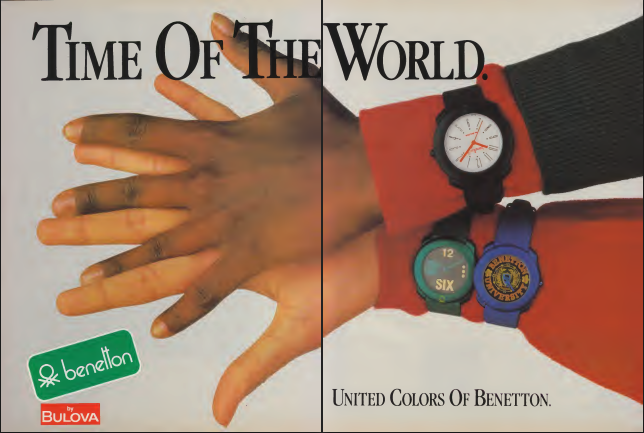

Authenticity is key here. If a campaign feels inauthentic to a brand’s story, companies risk making their customers feel manipulated. Merlo points to Benetton’s 1980s ad campaigns, where bold messaging on LGBTQ+ rights, racial diversity and AIDS activism was seen as outrageously political for its time, as examples of stirring the pot in a way that is true to a company’s values.

“It didn’t feel manipulative,” Merlo says, “there was a level of authenticity in it, in the sense that it went hand-in-hand with the positioning of the brand and its stance on social unity, tolerance, and all these values that the brand wanted to espouse.”

On the other hand, American Eagle’s supposed nod towards eugenics seems directly at odds with its stated purpose. Its latest annual report opens by saying: “Our purpose extends beyond making the best jeans – we embrace self-expression, culture, optimism, and connection. All are welcome at AE.”

We’ll have to wait and see whether Sweeney’s “great jeans” will continue to draw in new customers for American Eagle – the campaign came out right before the close of the company’s second fiscal quarter. Analysts will have a keen eye on the company’s Q3 earnings in December for a better understanding of its impact.

Regardless of what the numbers do, playing into today’s culture wars for clicks seems a far cry from the ethical business practices that companies claim allegiance to. Perhaps this is symptomatic of a wider departure from adherence to ESG principles and the rise of the “anti-woke” movement. As Merlo says, “If you’re trying to make people think, that’s one thing. If you’re trying to make people click, that’s a very different thing.”