Coughing season is here

Our shift in behaviour plays a vital role in the spread of infection

I remember clearly my grandma referring to the winter as “the season of illnesses”. She would wrap me up in scarves and warm knitted socks and I never questioned why the winter is always associated with more illnesses. If we stop to think, why do we really get a cold with the cold? Let’s explore!

The cold factor

The cold, dry winter air poses an inevitable hit to our defences. Every breath we take carries not only oxygenated air but also dust and pathogens (e.g. viruses). The mucosal lining of our nose acts like a filter, trapping and killing these pathogens before they can cause harm. But, just like any defence system, it needs the right conditions to work.

Research has shown that the cold air damages the nasal mucosa, decreasing the release of anti-pathogenic particles like interferons and extracellular vesicles, the weapons of our mucosal tissues. This dry air also dries the mucosal lining, reducing the trapping of inhaled pathogens. On the other hand, viruses tend to thrive at temperatures around 33ºC instead of the normal body temperature (around 37ºC). Taken together, a weakened barrier, fewer weapons, and increased viral replication in the colder weather leads to an increased likelihood of these intruders gaining the upper hand and triggering an infection.

Where’s the sun?

Another thing my grandma used to do in winter was cook fatty fish and take me to the park. As a child, I loved it, never actually questioning the science behind it. Fatty fish and sunlight exposure increase our vitamin D levels, a nutrient with a key role in boosting our immune system.

Among our immune battalions are macrophages, cells that patrol our tissues, identify invaders, and make them their next meal (just like us roaming around Tesco for a meal deal). These soldiers need vitamin D to regulate their activity and successfully protect us from infections. During the darker winter, less vitamin D weakens this immune response, leaving us more vulnerable.

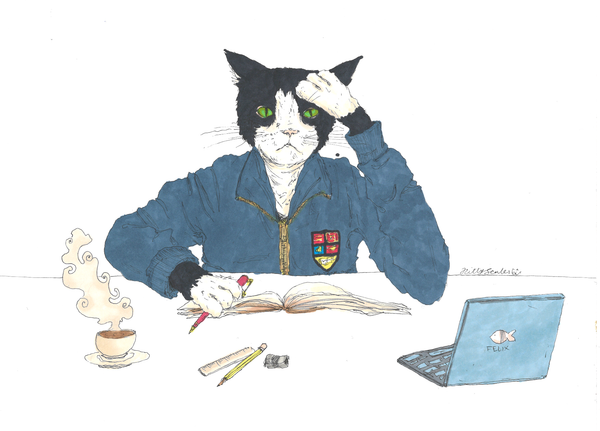

Let’s go inside

Summer is the season of picnics and long walks by the ocean. In the winter, we prefer indoor activities like studying at cafes or visiting museums.Our shift in behaviour plays a huge role in the spread of infection. Outdoors, the wind and larger volumes of air not only promote a quicker dispersion of infectious particles but also dilute them, making it less likely you will inhale enough pathogen load to make you ill. Indoors, a less ventilated, enclosed and rebreathed volume of air promotes pathogen accumulation, increasing the risk of airborne transmission. Just like my grandma used to say, “that virus thing going around” suddenly becomes more likely to reach you, just because it is able to accumulate more and closer to you.

We are walking clocks

Years of evolution have taught our bodies to predict regular fluctuations in light and temperature. While the circadian clock is regulated by 24-hour patterns in light, our seasonal clock is ruled by day length, temperature and rain patterns. Studies have shown that the number and action of circulating immune cells fluctuates throughout the seasons, reaching lower points during winter. With fewer and less active soldiers, we are more prone to getting ill.

So, what does this all mean?

In winter, our immune system may be weaker, but we are far from defenceless! Millennia of evolution have taught living organisms that the environment is never constant, and survival depends on adaptation. When my grandma wrapped me up in layers of warm clothes before letting me outside, she was drawing on generations of wisdom to protect me. The science of today finally allows us to understand how these methods work and find new and even better ways of protecting ourselves. Vaccines allow us to prepare our body and “teach” it to better fight off infections by giving it an opportunity to “meet” the opponents before the grand fight. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), “Vaccines have saved more human lives than any other medical invention in history.”

Some practical ways to prepare for winter include avoiding poorly ventilated indoor spaces, getting some sunlight (or supplement vitamin D), sleeping well, staying active and keeping up with vaccinations.

This “seasonal immunity” is a beautiful reminder that we are part of nature, and the changing seasons not only make the trees change colour and the soil smell of rain, but also shape our own bodies. While many more factors influence this, I hope I gave you a glimpse into the reasons why we tend to get ill in winter. Understanding these changes helps us adapt to the seasons and, one warm drink at a time, stay in tune with the science within ourselves.