The tiny molecule that answers a big question

The discovery of microRNA was finally acknowledged in this year’s Nobel Prize in medicine.

On Monday the 7th of October, the recipients of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine were announced: US scientists Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun, professors at Massachusetts Medical School and Harvard Medical School, respectively.

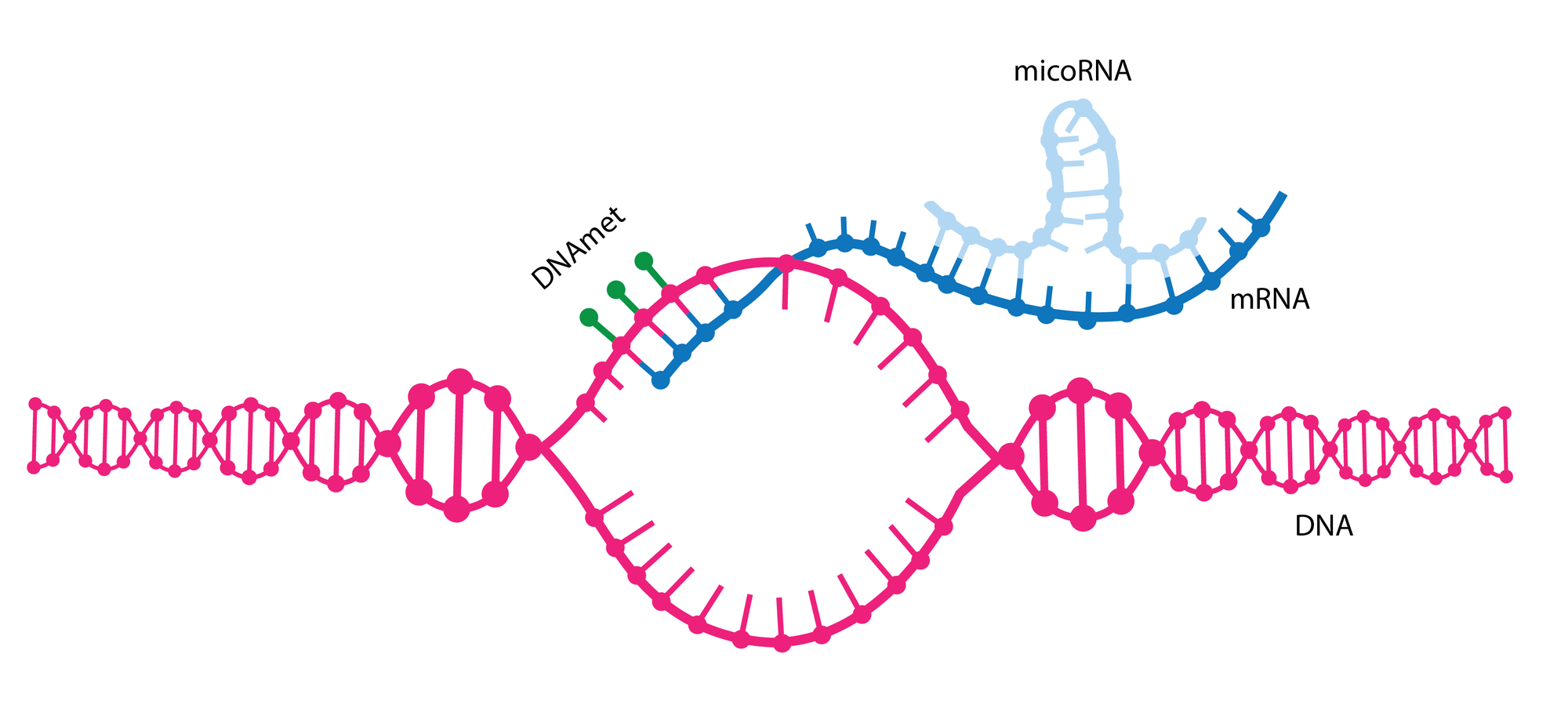

They were honoured with the title of Nobel Laureate – along with a shared prize fund of 11 million Swedish kronor, or £810,000 – in recognition of their work in the discovery of microRNA and its function in the regulation of genes at the post-transcriptional level.

Despite all cells in an organism containing the same DNA, individual cells still produce different proteins and perform various activities, depending on their role and position in the body.

The mechanism by which genes are switched off or on in different cells was relatively unknown until 1993, when Ambros made a seemingly insignificant discovery while researching the genetics of the unassuming roundworm

C. elegans.

Despite being less than 1 mm in length, C. elegans contains many specialised cells, such as nerve and muscle cells, that are also found in humans. Ambros discovered that microRNAs play an important role in the specialisation of these cells by binding to mRNA after the transcription of DNA, halting translation at the ribosome, and therefore preventing the expression of unwanted genes.

Even though this discovery seemingly answers the question of cell specialisation that puzzled scientists for decades, Ambros’s research was originally met with “deafening silence”, as the Nobel committee stated, since it was believed that microRNAs were unique to C. elegans and therefore of little significance in the medical field. That was until Ruvkun published his discovery of another microRNA that is highly conserved across the animal kingdom, including in human beings.

This breakthrough inspired a boom of research in the field, and it is now thought that the human genome codes for over a thousand individual microRNAs, all of which are involved in the regulation of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Now, over thirty years after Ambros’s original discovery, the two scientists have been recognised for this contribution by the Nobel assembly.

Ambros and Ruvkun’s discovery isn’t just useful in solving some of genetics’ biggest puzzles; it also has practical applications in medical treatment. It is now known that defects in gene regulation by microRNAs can contribute to cancers and genetic diseases such as DICER1 syndrome, which leads to cancers in many tissues.

“MicroRNAs are very much implicated in cancer. There is ongoing research to make treatments or utilise microRNAs—mimic microRNA or block microRNA—to treat cancer,” stated Thomas Perlmann, secretary-general of the Nobel Assembly. However, it’s not all been plain sailing: “There are some technical hurdles, so there have not been any drugs yet.”

Whatever the future holds for microRNAs in medical treatment, it is clear that Ambros and Ruvkun’s discovery has important implications for how we understand molecular biology and genetics. As Janosch Heller, a professor at Dublin City University, stated, “Their pioneering work into gene regulation by microRNAs paved the way for groundbreaking research into novel therapies for devastating diseases such as epilepsy, but also opened our eyes to the wonderful machinery that tightly controls what is happening in our cells.”