Greenpeace: UK exploits pesticide loophole

The UK government is once again placing the interests of large companies above the health of our planet and its inhabitants.

The UK government is once again placing the interests of large companies above the health of our planet and its inhabitants—this time allowing agricultural giants to ship thousands of tonnes of illegal pesticides to countries with less stringent regulations.

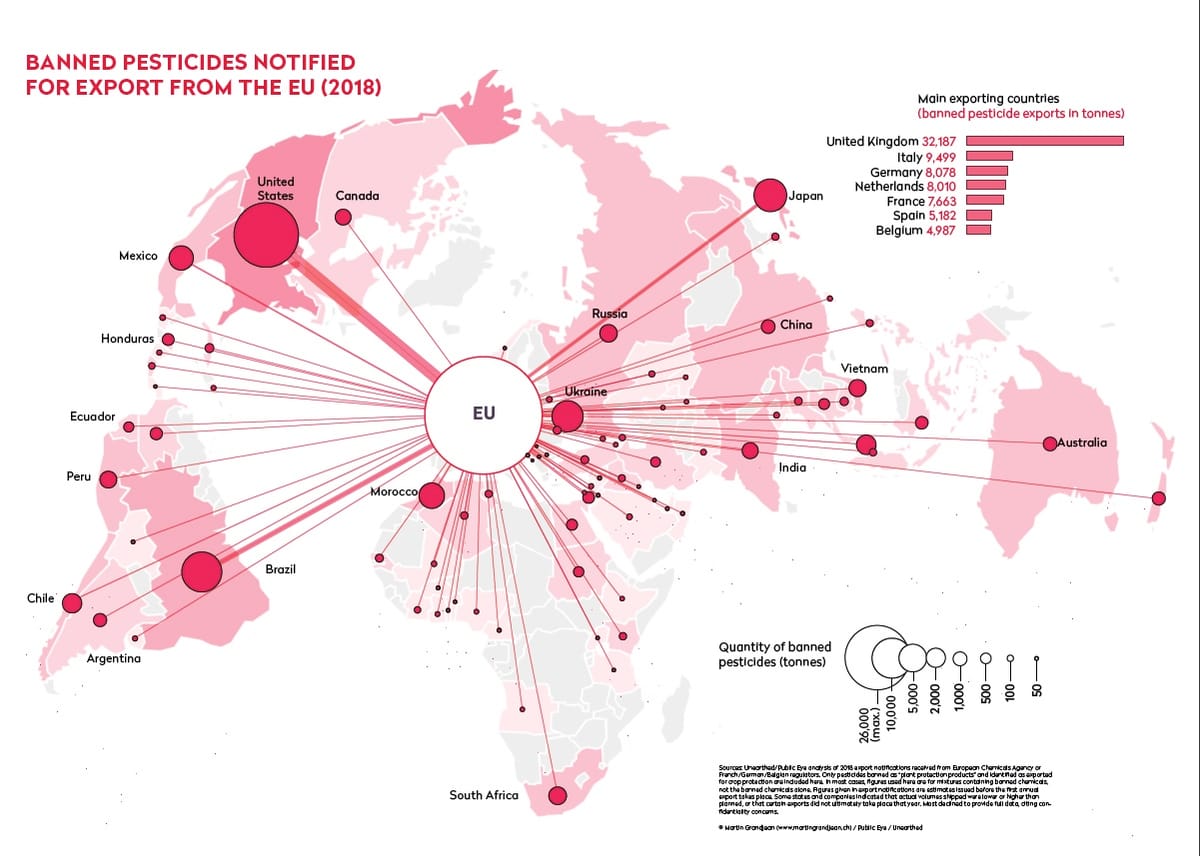

According to data unearthed by Greenpeace, the UK is not the only country to make use of legal loopholes allowing it to ship pesticides illegal for use under its own jurisdiction, however it is the largest exporter. Based on official 2018 figures, the UK exports three times more than the amounts shipped out by the second country on the list, Italy. It is also more than four times compared to Germany and France. As this data surfaced, the EU has stepped up to lead by example and ban the ongoing production and export of illegal pesticides, yet as the UK is no longer part of the union, such legal amendments will not be applicable within its borders.

But what is the problem—aren’t pesticides important for ensuring food security in our increasingly unstable environments and growing populations? Yes, pesticides can be important tools when tackling a variety of agricultural pests faced today, however, they encompass a wide range of chemicals. Pesticides are consistently tested, and new pesticides are constantly being developed leading to safer options available both for the planet and people (especially farmers).

Some of the insecticides shipped by the UK are the neonicotinoids, thiamethoxam, imidacloprid or clothianidin, which can have devastating effects on pollinator health. Bees, wasps and beetles act as ecosystem engineers, as their foraging behaviour allows the spread of flowering plants which provide the basis for a myriad of food chains. Neonicotinoids disrupt the behaviour and cognition of pollinators and increase their susceptibility to diseases which can increase their mortality and reduce their efficacy in maintaining our ecosystems. Furthermore, they can reduce the reproductive success of native pollinators, which are especially important for maintaining local species’ richness. Reductions in the populations of pollinators can therefore have downstream effects on biodiversity losses throughout entire landscapes as food sources for other species become depleted.

Pesticides are also continuously evaluated to ensure their safe contact with humans, but unfortunately not all of them pass with flying colours. For example, paraquat is so potent, a single sip of it can be lethal. So much so that it has become a common suicide method in countries where it is available and countries that have banned it such as Sri Lanka have seen major decreases in suicide rates. But similar to bees, humans can experience sublethal effects as a result of chronic exposure to pesticides and this has been widely linked to Parkinson’s, pulmonary and kidney diseases.

Yet despite all the evidence, regulations regarding this are wavering in the UK. While the problem may seem fixed at home, the global ecosystem is interconnected. By producing and shipping these chemicals to the United States, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Ecuador, we are ensuring that it is their people and ecosystems that will suffer instead of us. By its inaction, the UK government is actively prioritising the profits of large corporations over the lives of people and our planet. But who knows—perhaps with the interest of the UK to arrange trade deals with the US, maybe our pesticides will wind up right back on our plates one day.