Here’s why Imperial’s food emissions are rising

In Felix #1865 Food Editor Charlotte and I analysed Imperial’s catering procurement data to work out what we were eating on campus. I’ve taken that data and worked out how much Imperial is emitting from all the food we’re eating.

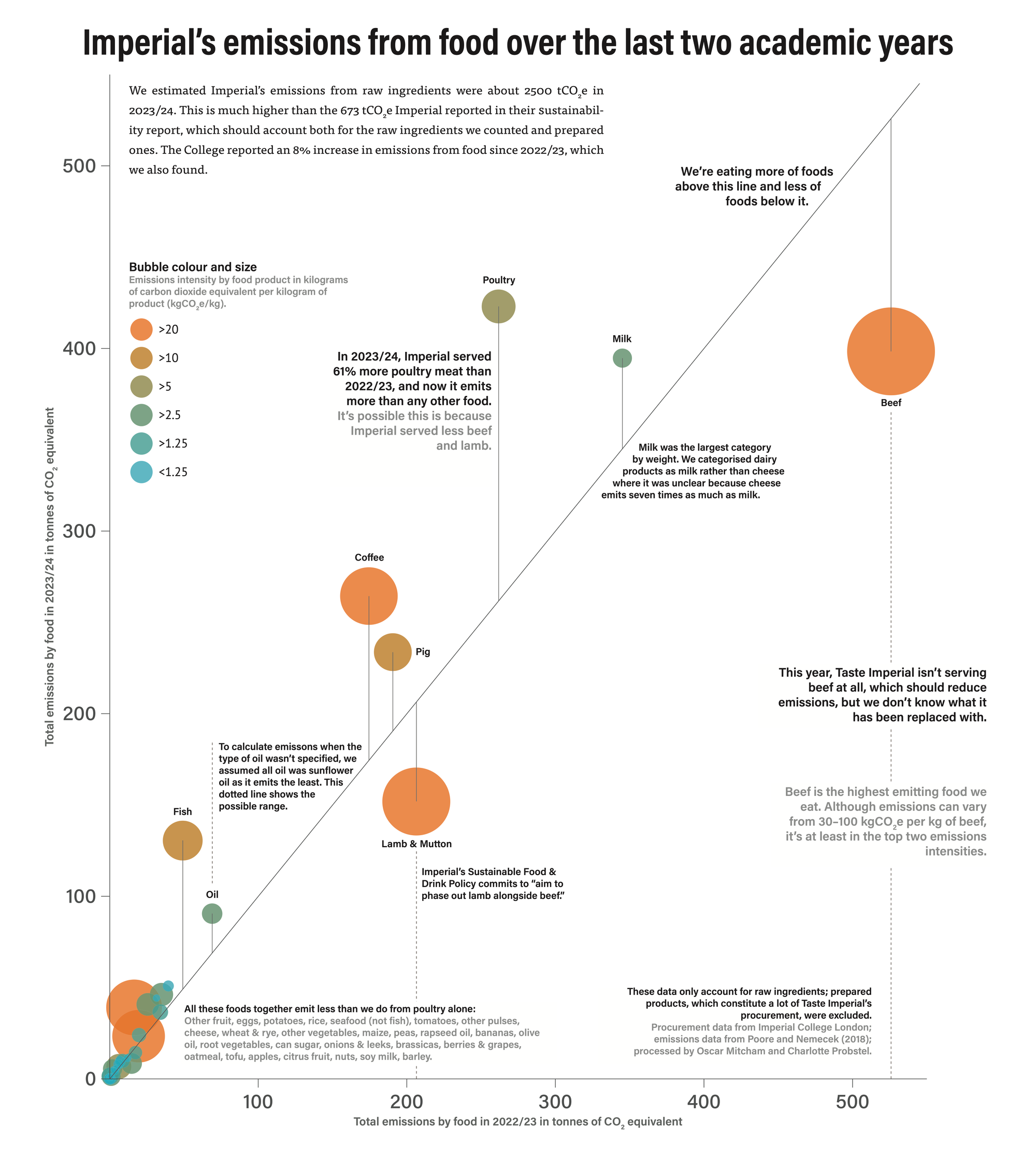

We estimated Imperial’s emissions from raw ingredients were about 2490 tCO2e (tonnes of CO2 equivalent) in 2023/24. This is much higher than the 673 tCO2e Imperial reported in their sustainability report, which should account for the raw ingredients we counted and prepared ones. The College reported an 8% increase in emissions from food since 2022/23, and we found a similar 14% increase.

I asked Imperial why its emissions had risen since 2022/23 and why our numbers might be larger than what the College is reporting. Here was their response:

“Imperial’s catering department is working hard to reduce the environmental impact of their operations, in line with Imperial’s Sustainable Food and Drink Policy. This includes removing beef entirely from our menus in October 2024, ahead of our 2025–26 target. We have introduced plant-based milks free of charge to encourage sustainable choices and we’re eliminating 30,000 plastic cups per year from our campuses with the single-use plastic cup 25p levy.

“The team are also increasing vegetarian and vegan options across all outlets. Improvements to back-of-house operations include reducing cooking oil consumption by 50%, and using the aquafaba left over from tinned chickpeas to make mayo, saving 26,000 eggs and 1,700 plastic tubs a year.”

Looking at Imperial’s carbon footprint methodology, it turns out that Imperial uses spend-based methodology for all its scope 3 emissions (83% of total emissions) except energy transmission and distribution. This means Imperial multiplied the total amount they spent on food by one number (a conversion factor) to calculate its emissions from all foods.

To calculate Imperial’s emissions from food, I used the product categories we worked out in #1865 and data from Poore & Nemecek (2018) which provides emissions by food in kgCO2e/kg of product. By accounting for how much of each food is actually being purchased, this method should give a much more accurate picture of Imperial’s food emissions. This is because emissions varies hugely between foods: for example, beef from a beef herd emits 30 times more than tofu. Since Imperial’s procurement dataset was so large, we only counted emissions from foods with clear product categories. “Apples” are apples, “poultry” is poultry, but we don’t know what’s in “flavoured (chilled)” or “lasagne.” While we could have gleaned a little more from the Item names, there’s no way to easily apply our methodology to pre-prepared foods like lasagne. So we decided not to count any of this. This probably makes our estimates conservative. However, the numbers we used are still global averages and there can be a lot of variation within each category. By contacting individual suppliers and using their carbon footprints, you could gain an even more accurate number. Presuming the suppliers even have emissions data, which is a big ask for prepared goods, you’d have to hope they were all using similar methodologies and reporting their scope 3 emissions.

This is part of why consistent emissions reporting standards are so important. The Carbon Disclosure Project is one system through which 18% of global corporate carbon emissions are disclosed. Unfortunately, only 67 agricultural companies disclose through CDP, accounting for 0.3% of agricultural emissions.

The College is aiming to improve its methodology using data from suppliers to calculate emissions. If achieved, this would be a step beyond our analysis.

As the College’s response outlined, Imperial has a sustainable food and drink policy that sets out their goals. It’s extremely heartening that no beef is being served at Taste Imperial outlets ahead of schedule. As you can see in the infographic (above), this will likely significantly reduce emissions, but we need to take the same phasing-out approach with other high-emitting foods. We will hopefully see even more action reducing these emissions following Plant-based universities’ recent motion passed by the Union Council.

Charlotte’s analysis found that Imperial only served 1.8 tonnes of plant-sourced protein last year compared to 98.8 tonnes of animal-sourced protein. Plant proteins are cheaper and less emitting than animal proteins, but the portions of plant protein are still small. This also needs increase rapidly to ensure the food being served on campus is nutritious and sustainable.

The infographic that accompanies this piece tells the story of Imperial’s food emissions and shows the results of our analysis. Emissions from 2023/24 are compared to those from 2022/23, with the diagonal line down the middle indicating no change in emissions. The colours and size of the bubbles show the emissions intensity of each food. Beef should have been given its own colour on the logarithmic scale used, as it emits on about 66 kgCO2e/kg.