In defence of bamboo

How it feels on the other side of “Western media” after the Hong Kong fires.

Skyscrapers surrounded by bamboo scaffolding and green netting are an iconic sight in Hong Kong. And since the inferno that killed at least 151 people, a lot of international media have questioned the use of bamboo.

As the Metro puts it, in its usual un-clickbaity manner, “All eyes are on an ancient method of construction.” The Daily Mail (the gold standard of journalism) proclaims, “bamboo scaffolding spread the fire.” The Independent simply declares, “Hong Kong’s devastating fire must spell the end of bamboo scaffolding.” Many British headlines, including some from The Guardian and the Financial Times, foreground bamboo, implying that its use as a scaffolding material contributed to Hong Kong’s deadliest fire since 1948.

It’s not hard to see why it seems strange to the rest of the world: bamboo scaffolding has been involved in over 20 deaths since 2018, and in March, the Development Bureau required half of all new public construction projects to use metal scaffolding.

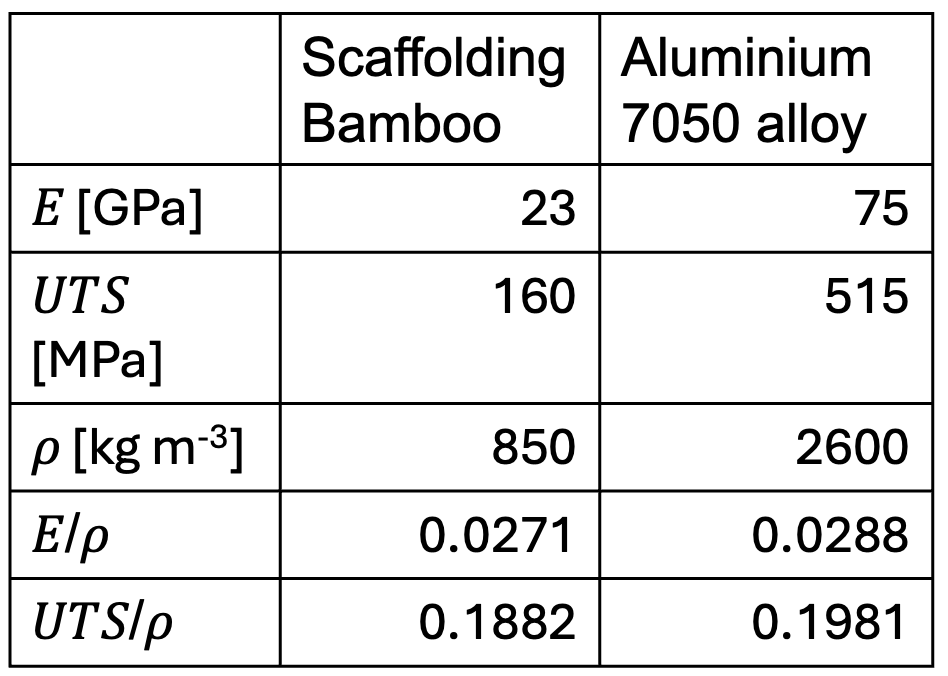

Yet bamboo remains the go-to option for construction in Hong Kong. Registered bamboo scaffolding masters use dried bamboo that must pass regulatory requirements, offering strength-to-weight ratios comparable to aerospace-grade aluminium. The poles are tied into trusses with nylon fasteners, then wrapped in a green mesh netting to catch falling debris. This cheap, customisable, and sustainable bamboo is used to quickly erect intricate scaffolds in cramped streets.

On social media, images showing intact bamboo scaffolding, where netting had long been incinerated, have gone viral. But burning bamboo lattices have also been seen falling dozens of stories to the ground. Bamboo is certainly more flammable than metal. Dr Bilotti of Imperial’s Aeronautics Department explains that polymers, such as polyethene, which scaffolding netting is usually made of, are very similar to hydrocarbons (such as natural gas) and thus highly flammable. They can be treated with additives that, for example, release water molecules when burnt or promote charring to prevent oxygen from reaching the parts that have yet to combust.

Last year, the Labour Department received residents’ complaints about the fire hazard posed by the nets. It responded that there were “relatively low fire risks” and that the mesh had “flame-retardant properties” meeting standards. It is unknown whether the mesh was tested. The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) found flame-retardant netting installed at the base of the buildings where tests would have been carried out, whereas the netting that was harder to reach was substandard. Compared to flame-retardant nets, cheap nets might have saved the contractor approximately $40 (£4) per flat. Since the fire, the ICAC has arrested 12 people. Other negligent practices include construction workers smoking, the “insane” use of highly flammable styrofoam window boards, and the deactivation of fire alarms to allow workers to use fire exits for convenience. Switching bamboo for metal is not the solution to corruption and negligence.

It is surprising how little nuance international headlines have shown the outside world. Ridiculous conspiracy theories swirl online, decrying the Western “cultural superiority complex” or claiming they are paid by steel companies to spread anti-bamboo propaganda. Then again, international media are not the only ones spotlighting bamboo. Hong Kong’s government has also proposed that its use contributed to the spread of the fire, whereas local social media sees this as a deflection of responsibility. University student Miles Kwan said, “The whole institution has broken down.” Kwan started a petition calling for an independent investigation into conflicts of interest, garnering over 10,000 signatures in a day, but former district councillor Michael Mo doubted the government would commission one: “[Chief Executive] John Lee would be cooked.” Kwan was arrested the next day on suspicion of sedition.

This begs the question of how accurately international media portray far more polarising issues in places less accessible to foreign reporters. Are Ukrainians still willing to fight on, despite Trump vacillating between “WIN all of Ukraine back in its original form” and peace proposals that were likely quite literally translated from Russian? How do the Sudanese feel about the stalemate between the government and the Rapid Support Forces?

To be fair, beneath the headlines, most articles did discuss other possible reasons for the spread of the fire, and mentioned that not everyone believed bamboo was at fault. But it seems we must choose between international media that sacrifices nuance for clicks and government press releases about “express[ing] gratitude towards President Xi”. (That said, if you do want to read English news about Hong Kong, you could do worse than striking a balance between Hong Kong Free Press and the South China Morning Post).