Inland Empire (2006)

A David Lynch feature: Starring Laura Dern

Inland Empire (2006), the third and final installation in the unofficial ‘L.A. trilogy’ (the others being Lost Highway (1997) and Mullholland Drive (2001)), focuses on a certain Hollywood actress. Starring Lynch veteran Laura Dern, Inland Empire depicts her character’s descent into madness as she accepts a role for the diegetic film that revives an old German film, which is itself based on a cursed Polish folktale. Dern’s performance is faultless, tackling the challenge of a role with a character arc not known from the beginning, with Inland Empire’s new script pages coming in daily, resulting in one of the strongest performances in all of Lynch’s works.

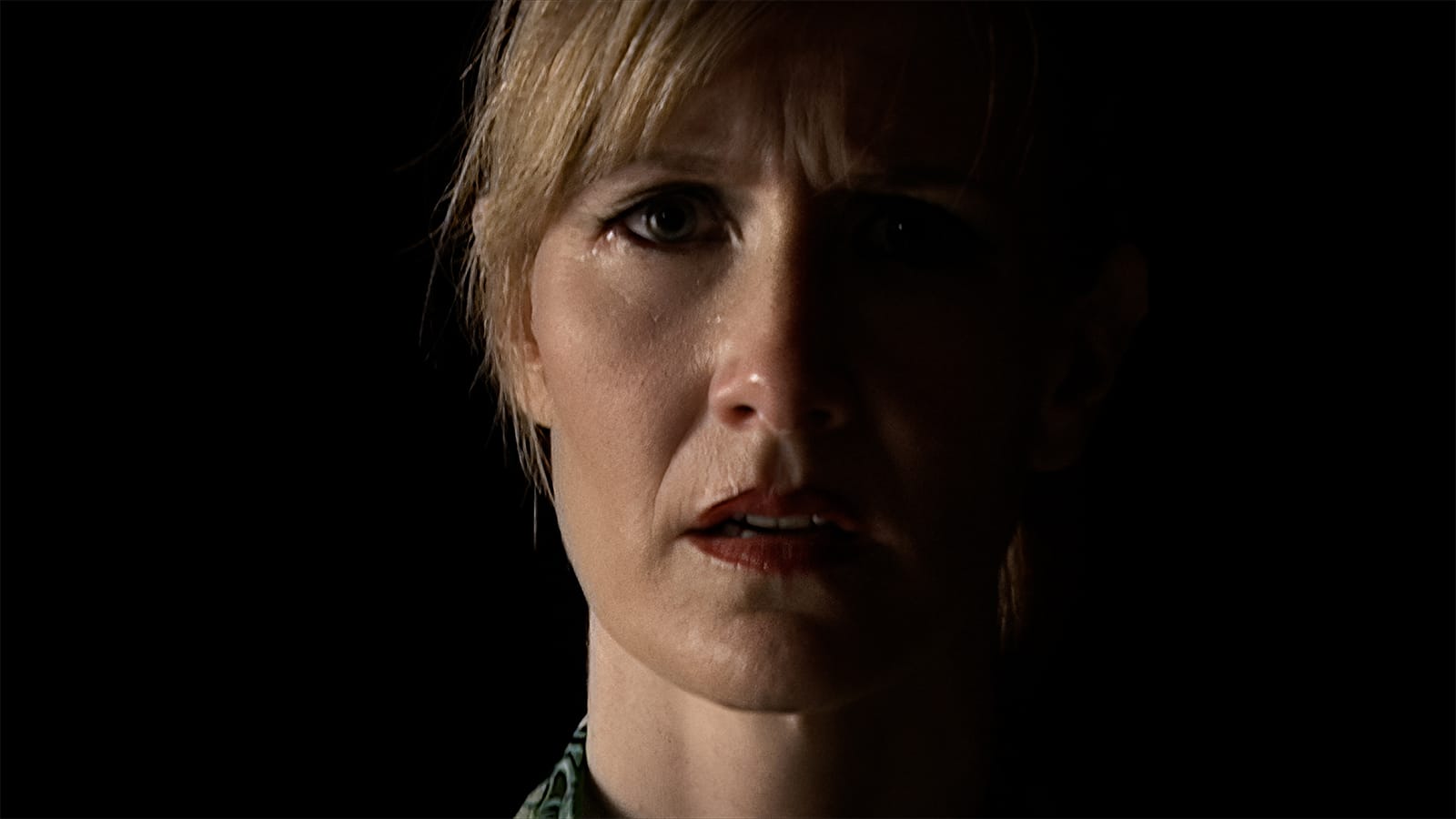

The improvisational nature of the production is reflected in the unintelligible plot of Inland Empire, making it one of Lynch’s most challenging films to interpret, even intuitively. The visuals match this with the film being made using a handheld, standard-definition digital video camcorder (Sony DSR-PD150), embracing the low-fi aesthetic. The digital format allowed for a guerrilla-style, intimate production giving Lynch “more room to dream” and the ability to create a harsh atmosphere for the viewers. This is a significant departure from the immaculate cinematography of Lynch’s previous features, replacing it with a style that fits the fractured narrative of Inland Empire. He used close-ups of actors that make up some of the most disturbing moments in the film (like Dern’s distorted face, shrieking into the camera, never losing its edge). Inland Empire marks Lynch’s first occasion of filming outside of the United States since Dune (1984). The gloomy, snowy streets of Łódź, Poland were the ideal location for Lynch to get out of his comfort zone. Eastern Europe was fertile ground for Lynch-land to find new roots, especially as a self-confessed fan of factories.

Lynch’s prowess and confidence is put on full display, with him scoring the whole film. The soundscape, characterised by ethereal dream pop, noir jazz and moody synths make the dramatic moments of the film even more potent. Lynch himself even sang many of the songs featured, and his most successful uses of pop in his work are displayed throughout Inland Empire.

Dern plays at least two roles – actress Nikki Blue and the character Nikki plays for the diegetic film, Sue – with exceptional skill. Her performance has significantly matured from Blue Velvet (1986) and Wild at Heart (1990), with greater nuance in her emotional expression and less over-the-top crying faces. Whether she is being the sweet Southern belle actress or the beaten-down wife, she is in complete control of work that could’ve easily strayed into parody, considering the shooting style of the film. Her acting is best displayed in the set of monologues she delivers as Sue, elaborating on her violent marriage and its consequences.

Jeremy Irons plays the role of the flamboyant film director, while Justin Theroux brings his role as Nikki’s co-star, Devon, to life with innate charisma. The true emotional performance is given by the Polish cast: Peter J. Lucas (Sue’s husband), Karolina Gruszka (‘The Lost Girl’) and Krzysztof Majchrzak (‘The Phantom’). Majchrzak proves himself comfortable with the role of the chief antagonist, ‘The Phantom’, a typical Lynchian evil-as-a-force bearer; he manages to imbue dread into every scene, even with a lightbulb in his mouth. Lucas delivers a strong performance as the abusive, threatening husband, whilst bringing a certain poignancy to a role prone to one-dimensionality. There are moments when Nikki finds herself in the original German film (or perhaps the Polish actors are turning up in the second film, or perhaps in her real life), which sometimes turns out to be a scene from the diegetic film, or something else entirely.

Some of the most nagging questions throughout the film are regarding the scenes of the humanoid rabbits. Where do they take place? What do they mean? These scenes are lifted directly from Lynch’s attempt at a sitcom, Rabbits (2002). The Edward Hopper-esque realm of these scenes has no geographic or temporal basis in Inland Empire, seemingly included to push Lynch’s improvisational instincts to the limit and majorly redefine a previous work. In what may seem a parody of sitcoms, the three rabbits serve as observers to the film’s maddening events.

Despite the impenetrable nature of the film, themes still manage to emerge: subconsciousness, Hollywood, identity, and even the movie as a metaphor for meditation. Lynch is famously a fan of Transcendental Meditation (TM), going so far as to set up a charity, the David Lynch Foundation, which aims to provide TM to at-risk groups and help them combat issues such as stress, PTSD, and trauma. Pre-enlightenment is a concept of one’s ‘self’ caught up in the moment of experience, and all experiences are seen to be some intimate part of selfhood, causing pain and suffering. Dern’s characters can be seen as metaphors for this through which the soul of the Lost Girl interacts with the world throughout history. These experiences drag her through terrible torment as she identifies with all of them. However, at the end, Dern kisses her, and she disappears, symbolising samadhi (‘pure consciousness’) where the observer, observed, and process of observation merge into a single point. This is pure self without any qualifiers. Samadhi is timeless because a temporal nature would make it part of observable reality. Thus, the Lost Girl remains still for some time until a knock attracts her attention.

Despite the impenetrable nature of the film, themes still manage to emerge: subconsciousness, Hollywood, identity, and even the movie as a metaphor for meditation.

Throughout the film, the flow of time is non-linear in every sense of the phrase; as Grace Zabriskie’s character puts it: “I suppose if it was 9:45, I would think it is after midnight”. In Inland Empire, nobody can remember if it’s today or two days from now, because yesterday and tomorrow, and every version of those, are all transpiring in the present. Take any moment, shot, sequence or motif, and you will find it repeated throughout at greater or lesser degrees of magnification. Like a fractal image, any single fragment contains a representation of the whole picture within. The aftermath of samadhi during TM is the feeling of all being right with the world: “that mother is home”. And so, as attention turns outward post-enlightenment, the Lost Girl finds her family is at home and that all is right with the world. This perspective sheds a new light on the end of the movie: the world continues, with a newly enlightened self behind Dern’s eyes, as she continues as an interested knower of reality. A rishi watching the play of pure knowledge with itself. And so, the play continues until the end of time (or the movie in this case). Lynch himself says, “We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream. This is true for the entire universe.”

Another interpretation is that it all takes place in the mind of The Lost Girl (Gruszka), who is freed of her past abusers by the successful completion of the diegetic movie. This would be one of the more optimistic endings in Lynch’s career, with Nikki setting The Lost Girl free to go back to her life without any of the tragedies that have befallen her – a far cry from the tragedies of Mulholland Drive or Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Here, both the fate of The Lost Girl and Nikki are wrapped in success and liberation. This mirrors the metaphor-for-meditation interpretation; the film is always seemingly rooted in Dern freeing the Lost Girl from her corporeal troubles.

The film can also be viewed as an allegory for the creative process; our protagonist, Nikki, goes to incredible lengths to bring her character, Sue, to life, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy while filming. She risks her physical and mental health whilst simultaneously ‘lifting the curse’ from a film that involved real-life murders. For Lynch, creativity is a healing process, where “a woman in trouble” (film’s tagline) can be expelled from their prisons and life traumas. The road to a successful product of creative energy can be paved with good intentions, even if the journey is materialised in a work filled with pain. “Put on the watch. Light the cigarette, fold back the silk, and use the cigarette to burn a hole in the silk. Then put your eye up to the hole and look through, all the way through, until you find yourself falling through the hole and into the shifting patterns you see on the other side.” This is a metaphor for making, and watching, movies; Inland Empire is overtly about the relationship between the movie and observer, the watcher and the watched.

It is a gruesome, yet gripping, glimpse into how vast the anatomy of Lynch’s imaginary universe is as it breaks down and contaminates itself.

At three hours long, it is a marathon, not a sprint, and stamina is essential to appreciate the movie. There are moments when the film seems to lose momentum, for example the seemingly endless sequences of the ‘Valley Girls’ sitting around, but Lynch always throws a curveball. The Valley Girls will act as a Greek chorus for Sue, before becoming spirit guides, then mocking bullies, then friends, and back again. The cyclical nature of characters’ behaviour and plotlines, wandering through personas and seemingly repeating sequences, is representative of samsara, a further link to TM. The length is necessary for a movie that continually alters the viewers’ perception of time. Even after, the movie still doesn’t feel over; it is still playing in the viewers’ head like a virus implanted by Lynch himself. He establishes a surreal series of wormholes between the worlds of folktales, movies, and reality, culminating in a conversation between two homeless women over Nikki’s wounded body about a prostitute with a pet monkey and “hole in her vaginal wall leading to the intestine”. It is a gruesome, yet gripping, glimpse into how vast the anatomy of Lynch’s imaginary universe is as it breaks down and contaminates itself.

Inland Empire is a film open to, literally, infinite interpretations. Lynch himself has refused to give a linear explanation, preferring audiences to “experience the film intuitively” rather than analyse it rationally. He maintains the film should stand on its own, without his post factum input, allowing viewers to discover their own interpretation. At most, Lynch describes the film to be about “A Woman in Trouble”, although this statement raises more questions than answers: shouldn’t it be “Women”? Or is this an accidental insight into his own thinking? He admits he has his own meanings for the film’s events, but maintains those meanings shouldn’t necessarily be anyone else’s – the film is “a world” to be experienced, something he will never explain.

After watching Inland Empire, one thing is certain: Lynch does not care about the audience’s expectations or the wishes of the masses. His storytelling is singular in both skill and creativity as Inland Empire undeniably proves; although it may be more appreciated by members who are fans of Lynch’s entire filmography, rather than those who are Twin Peaks fans first. Perhaps as Lynch’s most oblique work, it can be tempting to try and find a universal explanation for the labyrinthian plots and unreliable characters. Lynch himself may claim that everyone is a detective. However, to enjoy Inland Empire to the greatest extent, it is crucial to accept this film as an experience first and foremost, with an enlightened meaning being secondary.