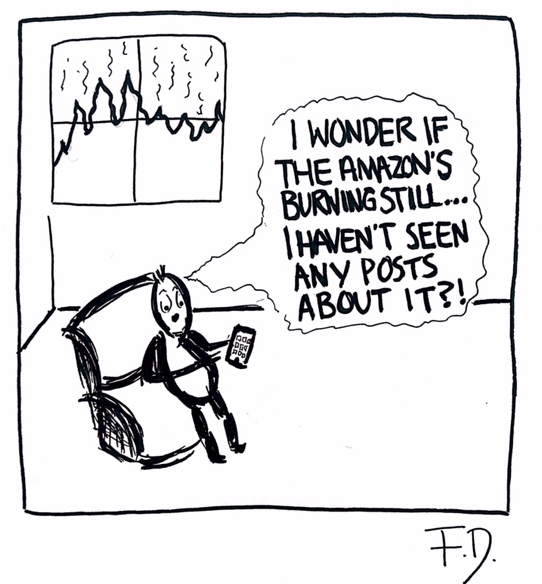

Is the amazon still burning?

The lack of outrage surrounding a topic does not mean that it has ceased to be a problem. Deforestation caused by wildfires and deliberate tree clearance in the Amazon continues regardless of its time in the public eye and this year could be worse than ever

During the summer of 2019, there was a surge of outrage and concern for the fires raging in the Amazon, in which 1 million hectares of forest were burned. There was unprecedented media coverage on the issue and social media shares skyrocketed like never before. And for good reason. From the period of January to August (2019) there was a 39% increase in forest loss than the same period in 2018. This increase was likely due to the policy changes President Jair Bolsonaro brought in when he came to office at the beginning of 2019 (this is the man who has been quoted saying, ‘Let’s use the riches that God gave us for the well-being of our population’ on a visit to the Amazon for a mining project).

The social media mania brought with it a flux of publicly accessible environmental education and awareness on Amazonian issues that environmentalists and local communities had been talking about for decades. Hundreds of celebrities with large followings urged people to donate to NGOs supporting the relief effort, and International leaders offered a relief fund to Brazil of $22.2 million, expressing global concern.

But where did our concern go? Considering the lack of rage and concern this, one may assume that the Amazon is ok now, and the fires all went out...

Deforestation increased by 51% in the first three months of this year compared to last year, soil is drier, and the temperatures are hotter. To understand why this is worrying we need to know how the fires occur in the first place.

Well, the Amazon is still burning, and this year could be worse than the last. Understandably, this year we have been preoccupied with other things such as the global pandemic and the civil rights movement which started in the USA over the summer. But the COVID-19 pandemic has hit Indigenous communities hard. And this year could be more damaging and destructive than the fires of 2019.

Deforestation increased by 51% in the first three months of this year compared to last year, soil is drier, and the temperatures are hotter. To understand why this is worrying we need to know how the fires occur in the first place.

Fires are not a natural occurrence in the Amazonian ecosystems. Most fires are caused by human burning of the remains of deforested areas; shown by the satellite images of fire hotspots being located next to agriculture, pasture, and roads. Of the area that was burned in 2019, two thirds were recently deforested (in the last few months). More often than not, land grabbers deforest public lands to transform it for commercial purposes. Therefore, the focus of policy change should be on minimising deforestation to prevent further transformation of more land into agriculture in the Amazon.

So, the combination of increased deforestation, drought, and increased temperatures create the conditions for more fires, especially from the beginning of the dry season in May.

In June this year, there were 19.6% more fires in the Brazilian Amazon than compared to last year, according the Professor Marcia Castro of Harvard University. Additionally, the numbers of fires have increased in Venezuela, Colombia, and Peru compared to last year.

It is crucial to highlight here that when forest is burned and transformed in this way, it may never fully recover. Since July there has been a ‘ban on forest fires’ in Brazil, yet there is a lack of enforcement and fires continue to burn.

This is terrifying. And for the Indigenous communities of the Amazon and areas around it, this is trauma; more specifically Solastalgia (anxiety and sorrow from the changes in the natural environment). Indigenous people are most affected by the deforestation and fires of the Amazon. For many groups, the forest is their livelihood and their home; fires and deforestation threaten this. The air pollution created by fires is also causing a spike in respiratory problems, with smoke poisoning becoming more and more common across Amazonia.

The Amazon is a huge carbon sink, but it could become a carbon ‘faucet’. It is our responsibility to reduce harm and further exploitation of the people and the ecosystems. We must stand in solidarity with the Indigenous people fighting for their lands and we can support them through organisations such as Amazon Frontlines. Plus, we cannot rest on our laurels and depend on the Amazon to be the ‘lungs of the earth’. We have the duty to increase our carbon sink potential in the UK if we have any chance of preventing further temperature rise across the world.