Tales of the Unsung Wilderness: Longlegs

You’re sitting on your couch, watching TV on a brisk autumn evening when you hear a faint shuffling on your carpet. You try to pinpoint the location of the sound as you warily turn your head, but there’s nothing to be seen. A few minutes later, it starts again. As you stand up and look at the corner of the living room, you see what must surely be a prop from a Halloween party - a dark, eight-legged beast scampering across your floor at speeds that shouldn’t be possible, the hair on its legs contrasting starkly with the plain white of your wall. Not in the UK, you think – this is what Australian nightmares are made of. If you haven’t already screamed and run in the other direction and have instead picked up a newspaper (or, worse, a vacuum cleaner) to send this fearsome beast back to the depths from whence it arose, wait.

This long-legged sprinter is most probably a male giant house spider, Eratigena sp. Some of the most frequently encountered spiders in the UK, Eratigena are usually the “scary ones” – the arachnids that strike terror into the hearts of innocent citizens with their size and speed. However, they are in fact incredibly shy creatures, cowering under the giant primates with whom they inadvertently cross paths. Despite their common name of “house spiders,” they are widespread and common in a variety of habitats ranging from gardens to the deepest, darkest woodlands. Females are large, with a body length (excluding legs) of a little under 2 cm and a leg-span of about thrice as much (1). However, they rarely stray from their webs. It’s the males, that suddenly mature in late August every year, that have to find them – and it’s these males that often end up in the wrong place at the wrong time. The legs of a large male GHS (as they are fondly called by British spider enthusiasts) (2) can span nearly 8 cm across, and he can run at half a metre per second (3). Why, then, shouldn’t he be feared?

Put simply, GHS don’t want to bite. And even if they did, it really wouldn’t cause you much of an issue. I’ve worked with spiders for over 2 years now, and if there’s one thing I can confidently say, it’s that it takes a lot of effort to get a spider to bite you. They don’t want to waste their limited venom stores on something they could easily run away from. Meaning unless you give them a reason to believe their life is in danger – for instance, squeezing them against something – they will always choose flight (4,4.1). Despite frequent sensationalised claims about people being sent to the hospital by a spider (5), the truth is that there are simply too many things that have to go wrong, and almost always don’t, for this to be the case.

GHS belong to a group of spiders called Funnel-weavers (family Agelenidae) (6) – not to be confused with the Australian Atracidae which are indeed rather deadly (7). They build an elaborate web consisting of a large silk sheet tapering into a funnel-shaped entrance within which the spider hides. When an insect stumbles onto the sheet, it is swiftly captured, bitten a few times, and dragged back into the spider’s lair to be eaten (8). This is a simple and elegant design that has worked in their favour for millennia. Fortunately, their adaptability means that they bring their patented bug-killing tactics along with them when they colonise a little corner of your flat. Being large spiders, they are capable of tackling all kinds of house pest from flies to cockroaches, without having to spray any pest-killing concoctions around your house. In addition, despite their fearsome appearance, they are no good in a fight, often being killed and eaten by considerably smaller species such as cellar spiders, Pholcus phalangioides (9).

Perhaps even more interesting than the biology of these spiders is their rich taxonomic history. The three species in the atrica group – Eratigena atrica, duellica, and saeva – used to belong to the genus Tegenaria before they were shifted to their current genus, a move which had little rationale besides being a somewhat sensible-sounding anagram of the original. Unfortunately, as is often the case with spiders, the three species look basically the same. How do you know they are three separate species, then? The most reliable character for telling spider species apart is their reproductive organs (the swollen pedipalps in males, and the epigyne in females) which are unique to each species.

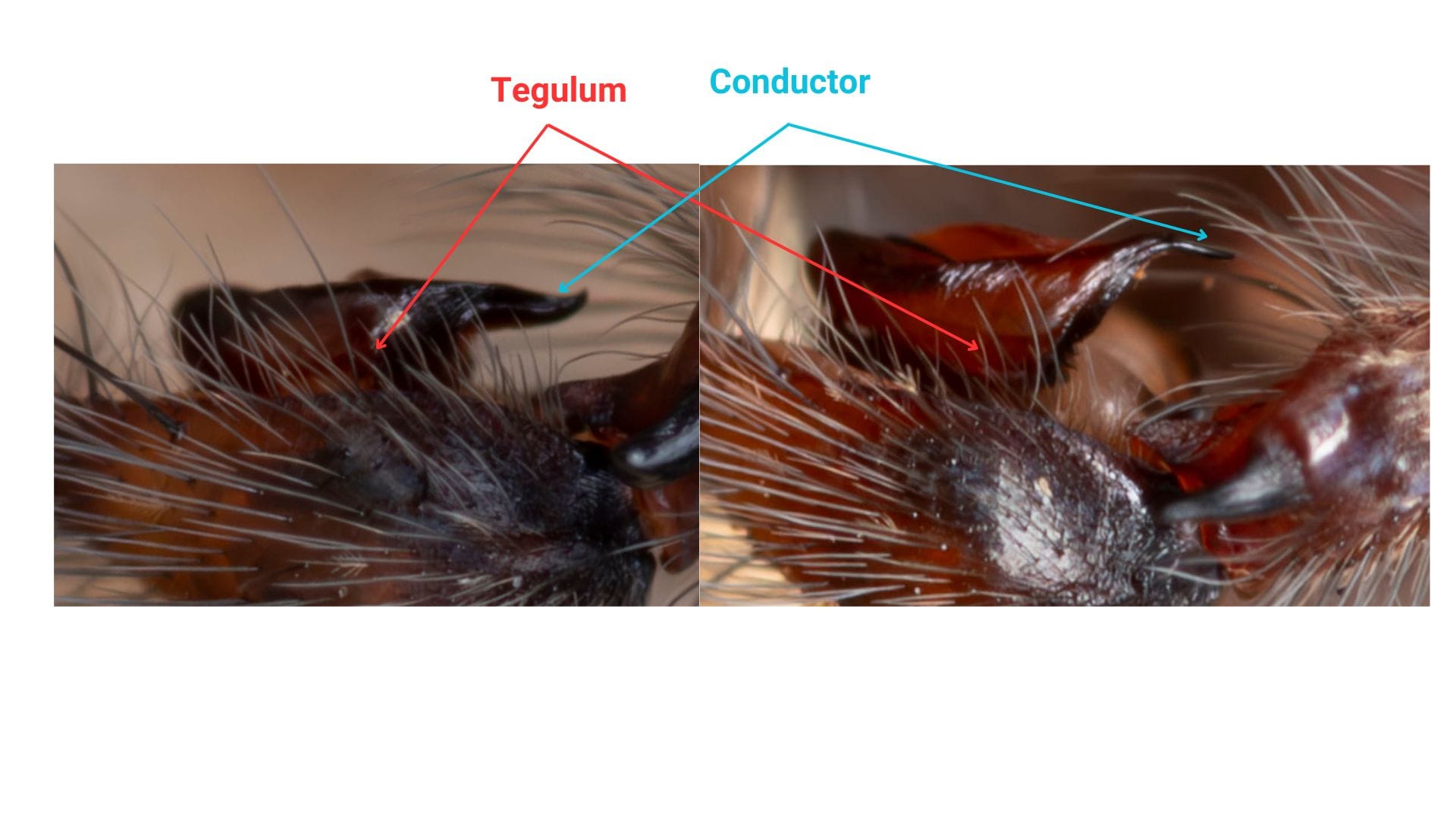

Sometimes the differences are clear-cut; other times, such as in the case of our friend Eratigena, the difference is as subtle as the angle at which a certain feature bends, or the thickness of a projection. In the case of E. duellica, saeva, and atrica, the difference lies in the shape of the tegulum of the palp, and how it merges into the conductor. In E. saeva, the tegulum bends nearly at a right angle into a thin conductor, while the bend is a lot smoother in E. duellica and the conductor thick and beak-like. Now, things get even wackier – turns out that Eratigena duellica is a mostly Eastern species while Eratigena saeva sticks to the west of the UK, but there is a considerable region of overlap in the middle where hybridisation occurs, and the palp morphology is somewhere on the broad spectrum from ‘clearly duellica’ to ‘clearly saeva’. This has prompted questions on whether the two species are truly distinct. Eratigena atrica, on the other hand, is a rare spider in the UK, and despite small populations in Newcastle and Scotland, it is generally imported by accident from mainland Europe (10).

GHS are not the only funnel-weavers in the UK. In most of the country, they are joined by the smaller and more colourful toothed weaver Textrix denticulata which is also often found in and around houses. I was quite pleased to discover a small colony of them on a plant outside my London flat, seeing as they are nowhere near as abundant in the Southeast. The hobo spider Eratigena agrestis is found at scattered locations across the country, generally under stones and logs in wasteland and grassland; there is a good population of them at Richmond and Bushy Park. Coelotes are heavily built, dark spiders that often reside in leaf litter and under logs in woodland, while the incredibly rare Eratigena picta has only been found in a couple of old chalk quarries. The true Tegenaria are represented in the UK by quite a few species, but only three are likely to be encountered. Tegenaria domestica – the common house spider – is similar to GHS but has short, striped legs and a different abdominal pattern; Tegenaria silvestris is found in a variety of natural habitats; and the impressive cardinal spider Tegenaria parietina is one of the largest spiders in the UK, with a legspan of 12 cm or more (11). It is the only species that can really be mistaken for a GHS, but both sexes have a dustier appearance with faint bands on the legs and often pale circular marks on the abdomen. While there have been records of them in houses, the cardinal spider seems to prefer old buildings such as churches and museums.

Now that you know all this (whether you wanted to or not) it is a fair ask on my part for you to leave the eight-legged chap in your living room alone. He means you no harm – he’s just looking for a mate and will be gone before you know it. If his presence bothers you, just pop him in a jar or glass and leave him outside. He will be perfectly fine: his ilk have been living in the cold long before you came about with your centrally heated house. Just look him in the eye(s) and wish him luck on his travels.