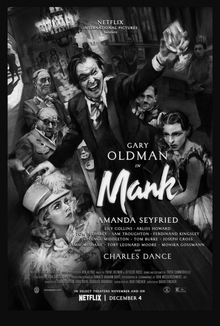

Mank ★★★☆☆

Film Editor Oliver Weir reviews one of the most highly-anticipated films of the year: David Fincher's 'Mank'. 'Mank' is a dramatised account of the Citizen Kane creation story and the inherent fight for credit that ensued between Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles. 'Mank' is streaming on Netflix now.

There seems to be a curious split in the critical response to Mank. Some have maintained that the evocation of 1930s Hollywood—which springs from a beautifully shot, though slightly fabricated, Citizen Kane creation story, and a script laden with stinging ripostes—was enough to make a masterpiece. Others have cited the same thing as evidence that the movie was inaccessible. I certainly side with the latter. I found myself appreciating Mank from a distance, trying to find some entry point, only to find the film unwilling to reciprocate the effort.

Visually, there is a great deal to marvel at. The endearing black and white cinematography of Erik Messerschmidt—who will undoubtedly win Best Cinematography next year—lovingly borrows from

Citizen Kane, but still maintains a touch of modernity. One can recognise the shots of unbroken sunlight in darkened rooms and the lingering fades from past to present, but its homage to Kane never feels affected. Mank has a soft digital lustre, an almost pastel sheen, that anchors it to the modern era and distinguishes it from a genuine 1930s picture. One cannot deny that the sumptuous cinematography and the excellent costume design, together with a narrative that is rife with historical studio in-fighting and political campaigns, combines to make a rapturous, albeit fragmentary, account of the era.

A rapturous, albeit fragmentary, account of the era

The inaccessibility of the film arises from having only a few items on its menu. If the audience does not connect to the era, or to Kane’s creation story, or to the myriad dramas in Hollywood, then they’ll be going home hungry I’m afraid. One might feel as though one can invest in Oldman if they cannot invest in the plot; however, I found Oldman’s Mank to be equally difficult. Oldman’s performance is good, though nothing special. He appears to have made the most of a character who is, in the way he’s written, somewhat unloveable and closed-off. Witty though he is, he does not use that wit sparingly. Nobody in the film does. All of the characters seem to be playing a game of fast-talking verbal point-scoring which really tests your patience after two hours. Truly witty scripts—like Sweet Smell of Success, for example—energise the audience, not tire them.

While it was somewhat interesting to see how Mank used his wit as a sword against his rivals, and as a shield to uphold his ‘tortured artist’ image to justify his alcoholism to himself, it was not exactly riveting. Fincher does not give us any more depth than this, making it very difficult for us to care about Mank. We rarely get to see his human side—only briefly at the end (in a scene with Welles (played by Tom Burke)) and in some scenes with Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried). For most of Mank he comes across as a cynic, a lonely man beweeping his outcast state, desperate to say something of note.

A beautiful film indeed, but not one made for me.