Music and the Climate Emergency

What can the music industry do to help combat climate change?

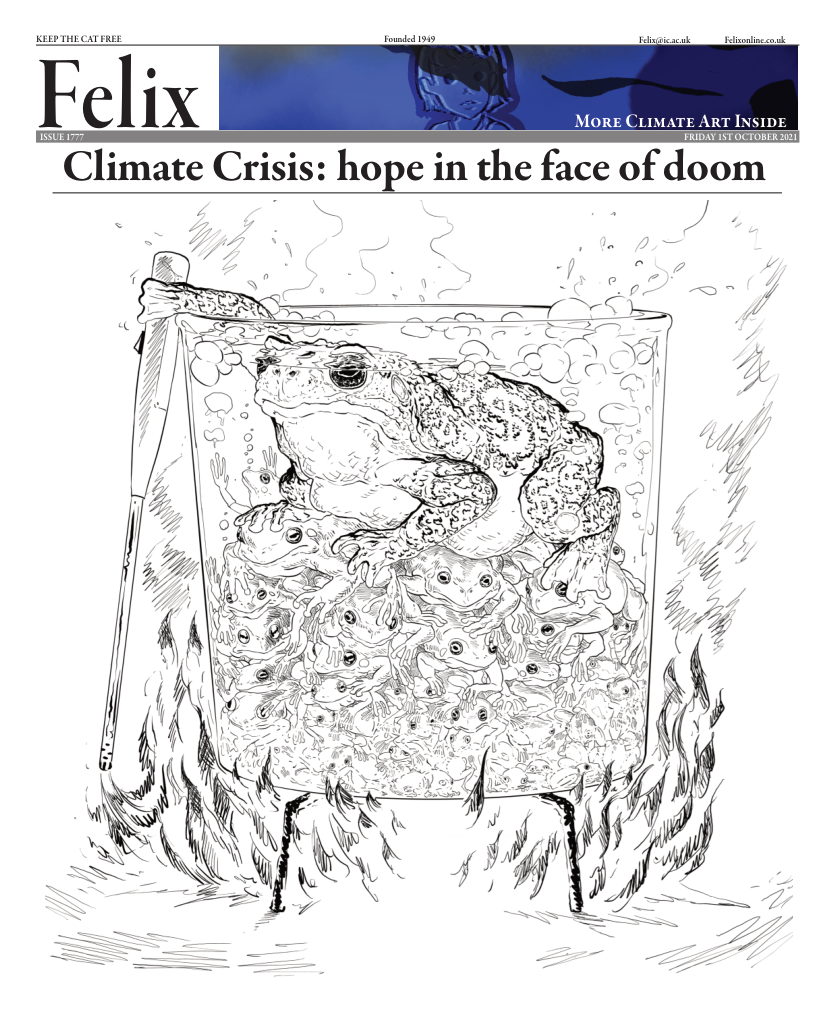

Mark Twain was once quoted as saying, “I want to be in Kentucky when the world ends as they are always twenty years behind.” Climate-anxiety and anticipatory grief are feelings many of us have begun to grapple with, as we fear time is running out to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis, many of which have begun to reach close to home. Avoiding succumbing to nihilistic defeatism about climate disaster is tricky, particularly when so much of what we hear is bad news, and when individual actions feel futile in the face of catastrophe.

What is next is up to us, and only future generations will know how we did.

The pressure we are all feeling is becoming reflected in unobvious industries. Take the music industry – I never considered how the arts could contribute to climate change until I heard about a report based on Massive Attack’s touring data by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research on the radio one morning. Since then, I have witnessed conversation about climate change permeate deeper within the music scene. After tuning in to the Ivors Academy’s annual lecture on music and the climate emergency, I realised these conversations had been ongoing for a long time – I just wasn’t paying attention.

This year’s panel was led by musician Brian Eno, alongside Professor Brian Cox, and climate scientist Dr Tamsin Edwards. The event was sobering, yet optimistic, best summarised by Edwards’ final comment, “Climate change is not something that is won or lost – it is a curve that we can keep bending down to a better future. What is next is up to us, and only future generations will know how we did.”

Art has the responsibility to try to enlighten, instead of just entertain

The conversation about the effect of the industry on the planet occur close to home. Eno admits many of his ponderings on what must be done occur whilst he walks through Hyde Park every morning. “Stop talking about the climate emergency and start talking about the climate opportunity,” he says, as he speaks of his house flooding on Christmas Day, and how this brought his community together with long lasting effect. “Climate change is the alibi we can use to change society to be the kind of world we would like to be in. We all know there are so many things wrong that are very intractable unless you have a huge excuse.” He details how many of the actions we must take to avoid climate disaster are actions that should be done regardless of disaster, in order to improve the world. He describes his goal to reform the music industry into a leading example of a sustainable, greened industry.

Fans must become actively involved in campaigns, support radical artists, and as the industry changes, be prepared to boycott artists who refuse to adapt to more sustainable practises.

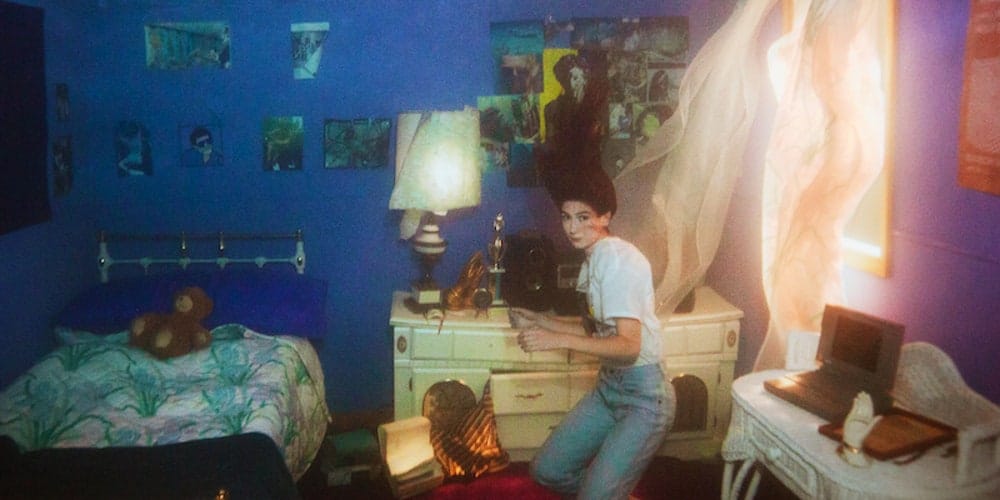

Despite the facts presented being bleak, the optimism and vision of the panellists provided hope against a background of existential despair – and even more musicians are becoming impassioned about climate activism. “Art has the responsibility to try to enlighten, instead of just entertain,” says Matt Berninger, frontman of indie-rock band The National – and artists are shouldering this responsibility, raising awareness through song across all genres. Standout climate activist songs include Anohni’s satirical “4 Degrees”, released back in 2016, Declan McKenna’s “Sagittarius A*” and All Star’s “Smash Mouth”, however my personal favourite is Weyes Blood’s Titanic Rising, an ode to the natural world and a warning to protect and nurture it. The album art features a teenage bedroom underwater, an image which strikes soberingly close to home for me - my hometown is forecast to be underwater in the next three decades if urgent changes to prevent sea levels rising are not made.

Political songs mean nothing if artists do not utilise their platform and privilege. Take Grimes, for example. Miss Anthropocene is a dystopian record focusing on environmental collapse (with no real substance), which is distasteful at best coming from the partner of one of the richest men in the world. This surface-level, performative activism highlights not only the class disconnect surrounding eco-collapse, but that political songs without activism is meaningless.

Coldplay, The 1975 and U2 are perhaps unlikely pioneers of climate activism within the music industry. Coldplay have refused to do tours that are not carbon neutral, and The 1975 launched the first UK festival powered by sustainably sourced biofuels and solar energy. Massive Attack partnered with the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research to study the effects of touring on the climate, releasing recommendations for venues such as switching to renewable energy, incentivising fans to travel via public transport to gigs, and for tours to be better scheduled to eliminate the need for private jets and minimise flying.

However, individual fans have a role too. Vinyl records are made from crude oil, after all, with only a small percentage being made from recycled plastics. Fans must become actively involved in campaigns, support radical artists, and as the industry changes, be prepared to boycott artists who refuse to adapt to more sustainable practises. There are many musician-led climate activist campaigns, such as the Music Declares Emergency ‘No Music on a Dead Planet’ campaign, which runs events such as Climate Music Blowout to fundraise for climate activism through live performances. This year’s event is happening at EartH, Hackney on 17th October this year, featuring live performances from bands such as Black Country, New Road, and Porridge Radio (tickets cost £15).

Changing the music industry is not the magic bullet to avoiding climate disaster, but every new policy and tonne of CO2 we can avoid emitting helps protect our future. I think back to Brian Cox’s words at the Music and the Climate Emergency lecture: “4 billion years to go from the origin of life to something than can think and feel and write music and do art […]. We live on a planet that has been stable for 4 billion years. The climate has not changed catastrophically enough to break the chain of life in 4 billion years. As we consider what we are doing to this little world tonight, it is worth bearing that in mind. It is possible that if we eliminate ourselves through inaction or deliberate action, we eliminate all meaning, all complex life, not on a planet, but in a galaxy.” Only future generations will know how we did.