Nosferatu: a symphony of sexuality

The gothic, the unknown, and why you should want to get freaky with Count Orlok

Robert Eggers has done it again. Nosferatu is amazing. The film, the second remake of the legendary 1922 production, offers one of the best additions to vampire and gothic cinema in a while. It is essential viewing: not just for the movie itself, but for its deep explorations of the themes of female desire and agency, more prescient than ever as we enter a second Trump term.

Following Thomas and Ellen Hutter, a newlywed couple living in Wisburg, the plot details their encounter with the malevolent “vampyr” Count Orlok. Based on Bram Stoker’s epistolary novel Dracula the plot deviates to its benefit – the character of Herr Knock (Renfield in the novel) works much better when there is a direct link between Thomas and Knock, rather than portraying him as a random maniac. The removal of the entire Lucy subplot works in streamlining a somewhat bloated novel: I read this novel for the first time when I was 11, and my constant critique has been that the initial horror and terrifying atmosphere built by protagonist Jonathan Harker dissipates in the middle. Not so with Nosferatu – its entire run time is tense. Every moment means something. Like every Eggers film, everything is carefully thought out. It’s a film made with deep love and respect.

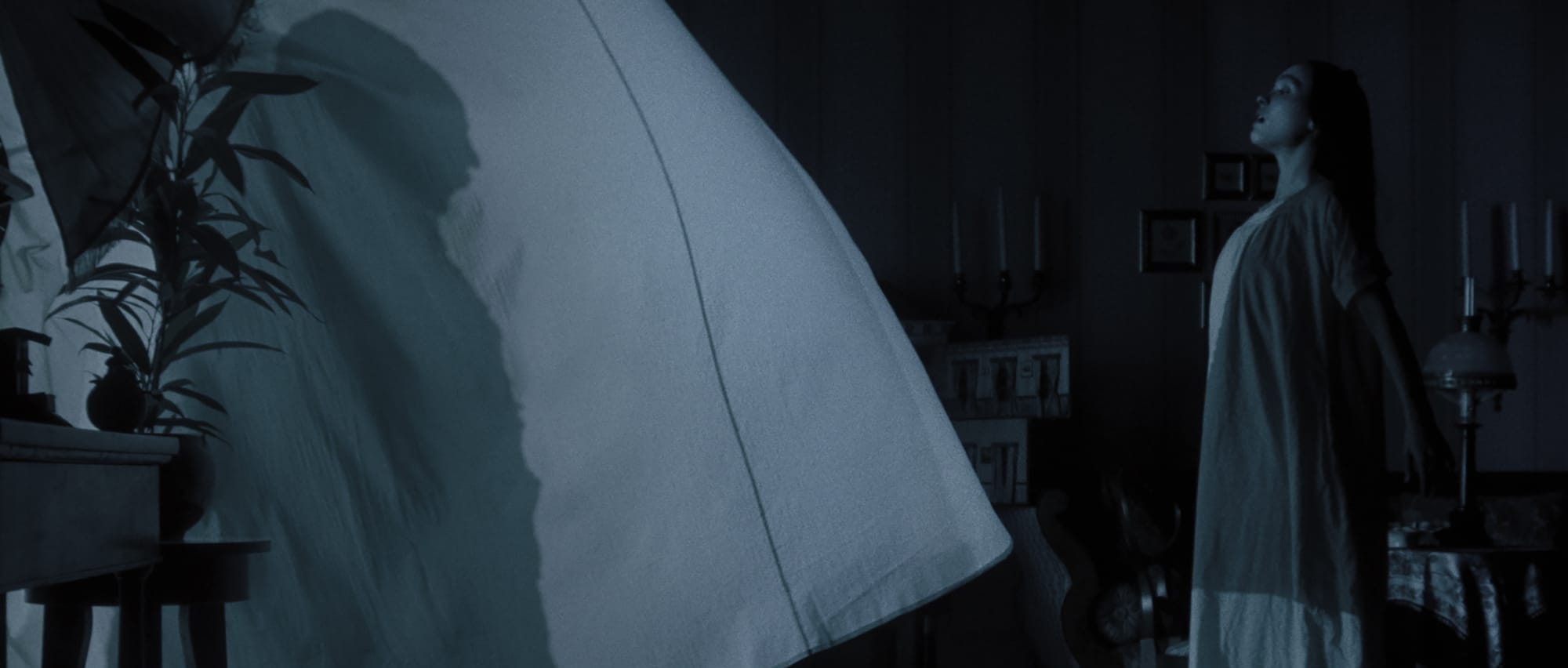

Robert Eggers’ origins as a set designer shine through. The sets are perfect – the locations used are perfect and fully capture the atmosphere he wishes for the film. It draws upon the original’s German Expressionist roots well. The scenes with Count Orlok’s hand shadows are pure kino. The shot over the streets of Wisburg is beautiful beyond words, and purely intentional as the plague overtakes the city. The scene of Hutter walking through the snowing forest, with its dreamy, painting-like backdrop, into the carriage is the most beautiful shot of the film, harkening back to the best part of the novel – the journey to Dracula’s castle amongst the snowy fountains, as well as capturing its German expressionism. On my first viewing, some of the shots felt unimaginative, or even contrived, particularly due to the reliance on centre shots, but on second watch, it elevated the experience. Everything felt much more dramatic. Eggers has said that his influences are Tarkovsky and Bergman, and it works to his benefit – in character-centred scenes, the blocking is organic and human, but at times exudes a quirkiness that just works. The grading, described by some as being too bland, works. There is always an atmosphere of bleakness. The blue hues used throughout accentuate the coldness, the terrible miasma gripping Ellen Hutter’s existence, the existential threat of Count Orlok, and make the film larger than life.

Lily-Rose Depp steals the show with her phenomenal acting as the main character Ellen. The sensuality she is able to portray whilst undergoing a seizure is haunting, as Count Orlok and she interact in some shadowy realm. Her chemistry with both Nicholas Hoult as Thomas, and Alexander Skarsgård as Orlok I found electric. Skarsgård is unrecognisable and seems to have morphed into Orlok. There is again, a sense of sensuality to his performance, as he imposes over the rest of the cast. Orlok feels unbeatable, he feels primordial, like a force of nature. My favourite shot of the movie is when we get a glimpse into Orlok’s eyes, as Hutter cuts his finger with a knife. There, wide-eyed, Skarsgård displays a range of emotions in a matter of seconds, going from surprise, to lust, to restraint, and with some faint rumblings of cunning, before it cuts to Nicholas Hoult again. His blood sucking is sexy. The scene where he straddles Hutter’s lifeless body, and the sound design of him gulping down blood is deeply erotic. I can’t believe I find a rotting corpse sexy, but Orlok makes it work.

Orlok feels unbeatable, he feels primordial, like a force of nature

Ostensibly, Nosferatu is about sexual assault. It’s about how the shadow of abuse and abusers can take over our lives and impact our relationships, particularly in a female context, where social expectations and norms reduce Ellen to an outsider. It’s an acceptable reading, but I believe the film goes further than that. Orlok isn’t shame, rather he is desire – he is the appetite, the fantasy, the need for companionship Ellen wants. It’s not necessarily that women’s sexual needs were viewed as non-existent, or taboo, as commonly assumed, rather that they were not viewed with the same depth as the sexual desires of men. Throughout Nosferatu we see couples having relatively healthy sexual relationships (spoiler: bar the necrophilia scene), but we never hear of their desires: Anna, the only other major female character in the film is only there for her husband’s desires for children and the enjoyment of the male, much more typical of Victorian couples. Ellen, and Count Orlok subvert this: there is a whole world, beyond science, beyond the contemporary medical ideas of the doctors of the era, that is unknown, spiritual, “celestial” insofar in that it is an essential part of the human identity, but sexual intercourse as a form of pleasure for the female subject, and for sustenance and to provide purpose for the male. Orlok needs Ellen’s blood – he is awoken by her, inverting the Victorian ideal that women needed sex to fulfil the purpose of the “maternal” life – a woman needs a man to have children, Orlok needs Ellen to fulfil his destiny. Of course, women’s desires are still taboo to this day, and Nosferatu acts as a beacon, without being overtly didactic, reflecting this, its depth as deep as the sky at night.