Of kleptons and kerplunk (Tales of the Unsung Wilderness)

If you were a fish in Permian Brazil, Prionosuchus was your most formidable foe. This gargantuan, vaguely crocodilian creature belonging to a group known as temnospondyls is thought to have ruled the waters of its time.[1] These impressive animals are no longer with us, but their successors (direct or not) remain some of the most prolific vertebrates on the planet. Whether you hear their resonating choruses on warm nights or spot their jelly-like progeny floating atop a tranquil pond, frogs form an integral part of the human relationship with nature. The unforgiving climate of the UK might seem too prohibitive for these warmth-seeking amphibians, but alongside the handful of native residents, one surprising visitor has managed to thrive here - the marsh frog (Pelophylax ridibundus).

Image 1: A large Marsh frog (Pelophylax cf ridibundus) basking at the WWT London Wetland Centre, May 2023 - Shreyas Kuchibhotla

Marsh frogs are majestic beasts, coming in many shades of green and brown. They can be distinguished from the native common frog (Rana temporaria) by their large size and lack of a dark “eyepatch” among other things.[2] Perhaps the most useful distinction, however, is independent of appearance. As Bashō’s haiku[3] goes:

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

This has been translated independently into English several times, such as this rather jovial interpretation by Allen Ginsberg.

The old pond

A frog jumped in,

Kerplunk!

Image 2: A large Common Frog (Rana temporaria) found at night in a garden in Hampshire, July 2023 - Shreyas Kuchibhotla

“Kerplunk” is perhaps an apt nickname for the marsh frog. It is one of their aural signatures, for they rarely leave a visual one. When walking by a pond in search of arthropods or grass snakes, I can barely begin to count the number of times that I have been taken completely unawares by a massive frog leaping noisily from right beside my feet into the water. The few times I do see a marsh frog for more than a second, it’s on a sweltering day in July when I look at the water’s surface and squint to catch a glimpse of its bulky frame blending in perfectly with the dull green of the surrounding aquatic vegetation. Marsh frogs love the water, more than any common frog ever could.

Amphibians in general are tied to water due to their reproductive biology, which requires their eggs to develop in a damp environment.[4] Common frogs take to the water in spring, when they mate and deposit their characteristic spawn on the surface. For the rest of the year, they spend their time in moist environments on land instead, often being found under logs, stones, and artificial refugia during the day. Marsh frogs however are rarely, if ever, seen away from the proximity of a water source. It is an almost foregone conclusion that a frog poking its head out of the water on a hot day, or kerplunking into a pond on a hot night, is a marsh frog. Despite their size, marsh frogs are considerably more skittish than their smaller cousins. However, during the warmer months, they make it their mission to be noticed. Adult males are endowed with considerable vocal power due to their distensible vocal sacs, but they have an extra trick up their sleeve – they can call in stereo. Unlike the common frog, marsh frogs have one sac on either side of their head,[2:1] and an unmistakable song to match. While the former has a more underplayed, guttural growl[5], the marsh frog likes its voice to be heard. The sound of a male marsh frog during breeding season is often likened to a laugh, and their distinct series of loud croaks[6] rivals even the waterbirds alongside which they frequently live.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of marsh frog biology is their intricate taxonomy, which borders on bizarre. Marsh frogs belong to the genus Pelophylax, which seems to defy all basic knowledge about the taxonomic boundaries of a species. The story goes like this: there are three closely related taxa in the genus – our friend of the marshes, the Pool frog (P. lessonae) and the edible frog (Pelophylax kl. esculentus). Even if you are familiar with binomial nomenclature, that “kl.” is a strange addition to a scientific name. It stands for klepton (from κλέπτω in Ancient Greek), the biological term for a taxon that steals genes from another taxon to reproduce.[7] The edible frog is, in that sense, not a “true” species, for the coupling of a male and female edible frog produces an unhealthy female marsh frog. For another edible frog to be born, a female edible frog needs genetic input from a male pool frog. Alternatively, the pairing of a pool frog and a marsh frog also produces an edible frog (likely the originator of esculentus populations, which generally live in syntopy with lessonae[8]). To further complicate matters, P. kl. esculentus is not the only such klepton in the genus – P. ridibundus appears to be capable of hybridising with two other species across its range (P. perezi and P. bergeri) to produce other kleptons (P. kl grafi and P. kl hispanicus). The other species in the genus also frequently come into contact, creating the possibilities for more and more outlandish hybrids.[9] These complicated relationships are the reason for the “cf” in all the image captions; while the species found widely in the UK is almost certainly ridibundus, it is difficult to discount the other members of the genus without closer examination.

Image 3: A frog identified as a young Pelophylax found well into autumn at the WWT London Wetland Centre, Nov 2023 - Shreyas Kuchibhotla

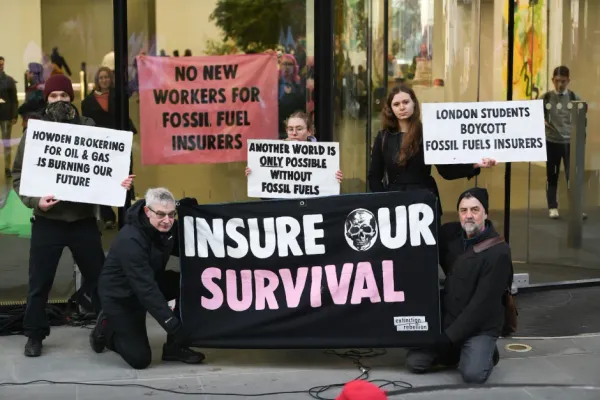

As charismatic and unique as they are, there are reasons to be worried about marsh frogs in the UK. They were apparently introduced deliberately to a site in Kent in the early 1900s, following which they have spread like wildfire throughout the south of England, especially in and around London.[2:2] They have been named the “number one amphibian invader in Western Europe”.[10] Herpetologists seem to recognise that the increase in marsh frog populations is not as unambiguously destructive as one is often led to believe with non-native species.[11] While they are the dominant amphibian where they are found, they exploit habitats that native species do not, like saltmarshes. Their predatory behaviour and disease-carrying potential are of course major risks, but their size and habits make them easy prey (and consequently good news) for native barred grass snakes (Natrix helvetica). On the other hand, while marsh frogs are not native to the UK, there is evidence that pool frogs used to be, and they have been reintroduced to a select few sites in Norfolk in an attempt to restore their previous populations.[12] If the marsh frogs were to interact with them, the complex population dynamics engendered by the klepton saga might be unpredictable. In my experience, the best site to see them in London is the WWT Wetland Centre (where most of the photos in this article were taken). It is telling that I have never seen a common frog there, though whether this can be chalked up to different habitat preferences or the genuine consequences of a dominant and invasive competitor is still moot.

Image 4: A Marsh Frog (Pelophylax cf ridibundus) photographed at the WWT London Wetland Centre showing how easy they can be to miss, Nov 2023 - Shreyas Kuchibhotla

Non-native species are always a mixed bag, but in a world where globalisation is the norm, the movement of animals and plants across man-made borders happens more often than we think. The effects of such species on the environment can sometimes be difficult to assess until it is too late, while others seem to occupy specific niches (e.g. by living alongside people) where competition is non-existent or ultimately harmless. Whatever the marsh frogs eventually accomplish in the UK, they are here to stay. Come spring (as it continues to take its own sweet time), you might as well look for them on the water’s surface or listen for the “kerplunk” as their surprisingly well-camouflaged bodies evade you yet again. I know I will.

Cox CB, Hutchinson P. Fishes and amphibians from the late Permian Pedra de Fogo formation of northern Brazil. Palaeontology. 1991 Jan 1;34(3):561–73. ↩︎

Booy O, Wade M, White V, Winchester D. Marsh Frog: Species Description [Internet]. Non-native Species Secretariat. Available from: https://www.nonnativespecies.org/assets/Uploads/ID_Pelophylax_ridibundus_Marsh_Frog.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Basho’s Frog Haiku: 32 Translations [Internet]. www.bopsecrets.org. Available from: https://www.bopsecrets.org/gateway/passages/basho-frog.htm ↩︎

Habitat management for amphibians [Internet]. The Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust. Available from: https://www.arc-trust.org/for-amphibians ↩︎

Amphibian & Reptile Conservation. Common frogs calling and spawning [Internet]. www.youtube.com. 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPXwkkjhKXE ↩︎

UK Wildlife. Marsh frogs calling at RSPB Rainham [Internet]. YouTube. 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbCdxSAO4fg ↩︎

Bosch DL. Hybrids and sperm thieves: amphibian kleptons [Internet]. All you need is Biology. 2016. Available from: https://allyouneedisbiology.wordpress.com/2016/07/24/amphibian-hybrids-kleptons/ ↩︎

Holsbeek G, Jooris R. Potential impact of genome exclusion by alien species in the hybridogenetic water frogs (Pelophylax esculentus complex). Biological Invasions. 2009 Jan 30;12(1):1–13. ↩︎

Christophe Dufresnes, Monod‐Broca B, Bellati A, Canestrelli D, Ambu J, Wielstra B, et al. Piecing the barcoding puzzle of Palearctic water frogs (Pelophylax) sheds light on amphibian biogeography and global invasions. Global Change Biology. 2024 Mar 1;30(3). ↩︎

Dufresnes C, Leuenberger J, Amrhein V, Bühler C, Thiébaud J, Bohnenstengel T, et al. Invasion genetics of marsh frogs (Pelophylax ridibundus sensu lato) in Switzerland. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2017 Dec 30;123(2):402–10. ↩︎

Allain S. The Story Of The Introduced Marsh Frog - SAVE THE FROGS! [Internet]. SAVE THE FROGS! 2019. Available from: https://savethefrogs.com/marsh-frog/ ↩︎

England’s rarest frog returns to Norfolk (more info) [Internet]. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2016. Available from: https://www.arc-trust.org/pool-frog-norfolk-more-info ↩︎