Physics department “unhelpful”, “dismissive” and “two-faced”, say students

Imperial's Physics department among bottom five in country from 2017-2022, according to NSS student satisfaction scores

“It was absolute chaos”, says Alex, when we ask them about their time as an undergraduate in Imperial’s Department of Physics. “It just felt like you were getting by somehow.”

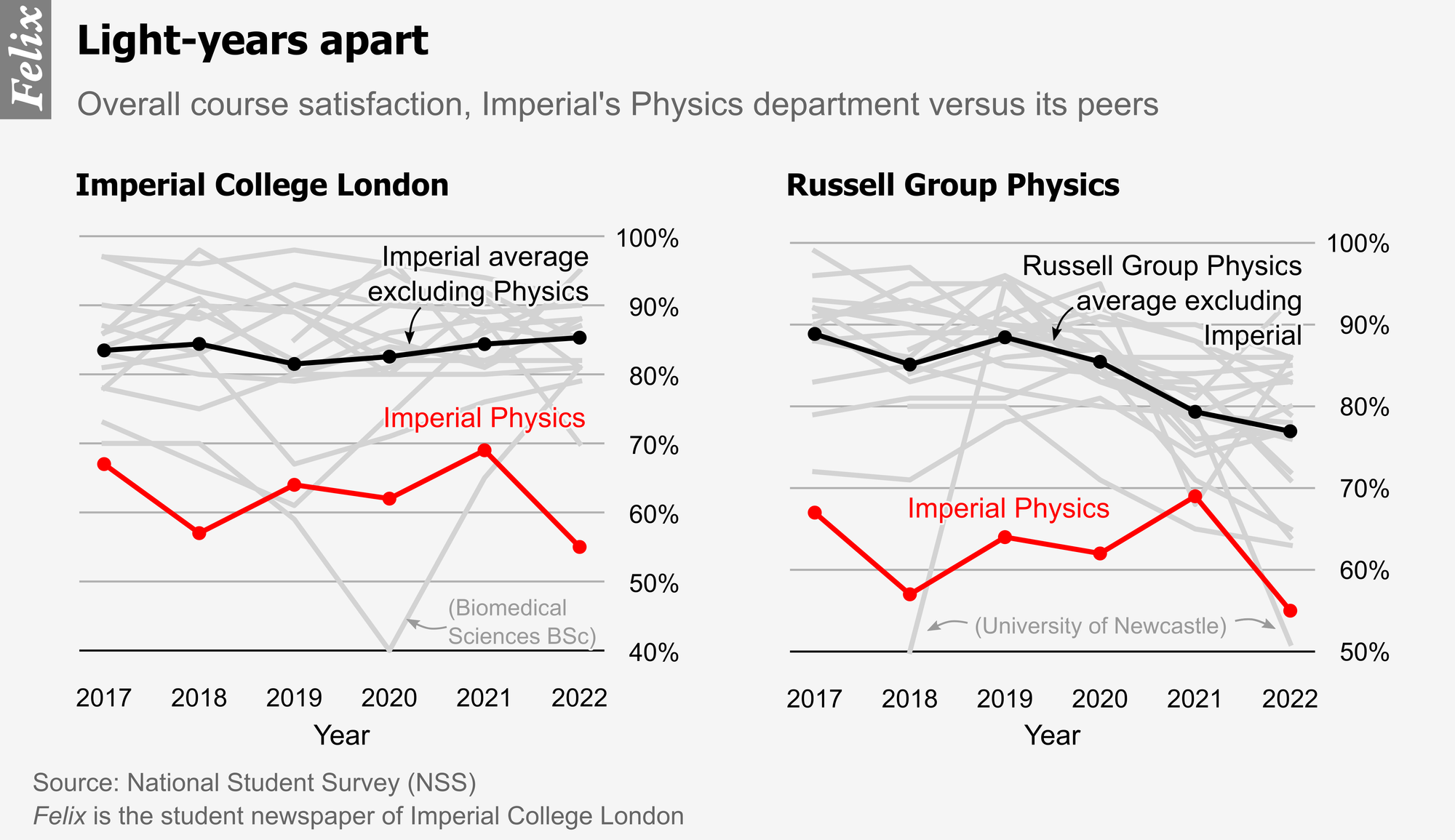

Alex (not their real name) is not alone in their sentiments. For several years now, the department at Imperial has had notably poor student satisfaction. In the 2020 National Student Survey (NSS), which was sent to all final-year undergraduates in the UK, it was the lowest-ranked Physics department in the country for overall student satisfaction. It holds the unfortunate distinction of being in the bottom five Physics departments in the country on this measure, in every year from 2017 to 2022.

Physics is an aberration amongst Imperial's undergraduate courses; the College as a whole has consistently achieved high student satisfaction scores, and over the past few years, has been ranked among the best in the country. Last year, it won The Guardian’s University of the Year Award.

Viewed in this light, the Physics department's performance is puzzling. Felix set out to understand what it was that led its students to express such dissatisfaction. We spoke to a range of undergraduates, who painted a picture of a department remarkably out of touch with its student body.

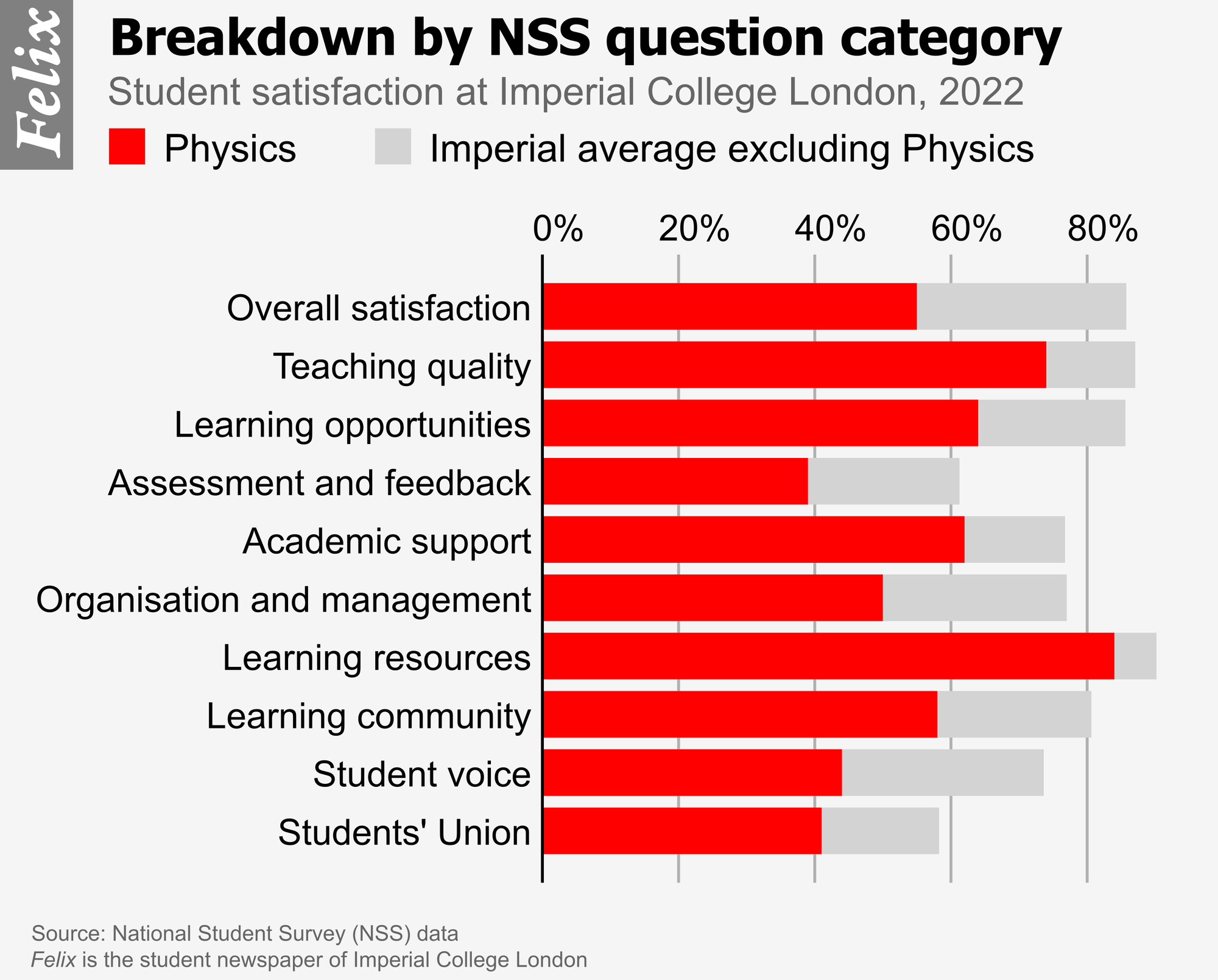

A litany of problems plague the department. An unwavering insistence on maintaining academic standards leads to hefty workloads and tight deadlines. Then, a perceived reluctance to empathise with students and accept culpability for the resulting issues leads to accusations that the department is apathetic and defensive, and that its student-support mechanisms are perfunctory and tokenistic.

One student told Felix, “The workload is so high that it leaves students very stressed and very overwhelmed with what they're doing. That is not an environment that's conducive to good mental health or being able to enjoy yourself in London.”

Many students speak of a problem of overassessment. “There are too many extra little tasks — an extra problem sheet here, an extra bit of coursework there. They don’t add a whole lot to the course.”

A fourth-year physicist gave the example of assessed problem sheets: “It was devastating — late nights and high stress for maybe 2.5% of a module.” He said that he never received feedback on the problem sheets and was sometimes unable to identify where he had gone wrong.

I no longer knew why I was doing Physics; the degree had taken the fun out of it

Discontent with feedback is widespread. Across year groups, students feel that the marks they are awarded are not proportional to the quality of their work or the effort that they put in. Several students felt marks were awarded at random. “It was really very frustrating to put so much effort into a piece of coursework for it to be up to a roll of the dice”, said one second-year physicist.

The quality of help provided by teaching assistants (TAs) varies significantly. “The TAs are a bit of a crapshoot”, explains a Physics undergraduate. “Some of them are excellent and some you learn to avoid.”

The same, students say, is true of laboratory demonstrators. They claim that demonstrators didn’t understand the nuances of the experiment, and would have to consult the heads of experiments — who were often not present.

Others describe being paralysed by the demonstrators’ inattentiveness, whose response to some questions was simply, “Google it.” One undergraduate told Felix, “You have to spend so much time just figuring out how to start the bloody project. That's one of the most frustrating parts.”

The best representation of how this course makes me feel is the scene from Indiana Jones where the Nazi's face is melting

Deadlines

Exacerbating the problem is a tendency for deadlines to be stacked together. One student recounted an incident when they alerted the department to a deadline crunch; its response was to bring one of the deadlines forward.

“Responses like this just lead students to think the department doesn’t care about them”, said a former student representative.

Even when empathy is shown by individual teaching staff, students feel that there is a culture of obstinacy in the wider department. A student told us how in her third year she had four deadlines in one week, with multiple falling on the same day.

“We spoke to the lecturer of one of the modules, for which two of the assessments had ended up on the same day due to the strikes. They were lovely and said, ‘Yeah, that sounds fine. This doesn’t seem right that you're getting this kind of unfair knock-on effect because of strikes. We just need to check with some other people in the department.’ We got a response from the department saying, ‘No, you can’t do that.’ Even though the lecturer wanted to.”

Office hours are available for students with queries; yet, as a fourth-year student explained, “People are in two minds about it. Either they understand it so they've got nothing to ask, or they're too far behind to even bother going.” This dichotomy seems to dissuade students from going, as one second-year student tells Felix. “No one who should go to office hours goes to office hours. People would much rather just struggle and not have any sort of contact with members of the university than actually attend office hours.”

A welfare representative suggests this is a consistent theme: optional events to answer students’ questions are attended only by a small group of students who are up to date on their work and go out of their way to attend. “The people that are struggling — they don’t actually get all this information because they're not attending these events.”

“I think it’s these people we need to be reaching out to the most. For example, many of those who are really behind on lectures don’t actually know that they can get help with that, so they fall even further behind.”

The representative reported these problems to the department, but said the year group organiser’s response — “Tell person X about it” — was of no help. “If most of the cohort is stressing out, they’re not all just going to go to this one person, because clearly the problem is bigger than that. I mean, [the year group organiser] didn’t really take any action on that.”

Left adrift, students are banding together to offer each other the learning support they feel they are not receiving. The current first-year cohort has asked its representatives to create study groups for them so they can solve more problems together. Most students find that their best source of help is their cohort’s group chat, which several said was better than the support provided by lecturers and the department. Already, older students run a helpdesk (sponsored by the department) where students are encouraged to take queries. One third-year student found this was the “most helpful” outlet she had during her degree.

Welfare

Whilst the problems stem from a high workload, the department’s attitude to wellbeing, and its welfare provision, have been roundly criticised. There is a general sense that the department does not take its students’ mental health seriously enough.

“I think for many people the best representation of how this course makes them feel is the scene from Indiana Jones, where the Nazi’s face is melting”, says one second-year student. “The department can see how stressed we are, but what do they do? Nothing. Do they care? No.”

A third-year student told Felix that her emails to admin staff — requesting additional arrangements to accommodate a medical condition during an exam — were ignored. It was only when she got the Head of Department involved that she received a response.

Welfare events held by the department have been mentioned by several students. “Instead of solving the problem at hand, they provide support such as tea and biscuits, which just seems like the complete wrong approach and doesn’t actually help”, says one student.

Students’ experiences with their personal tutors vary. Some have praised them as “absolutely amazing”, but others find their tutors apathetic and indifferent.

One third-year physicist was scathing: “I think my personal tutor doesn’t really care. I tell him the same things every time, and he forgets them between meetings… he’s not really supportive.”

“There are members of the department who are accredited ‘Mental Health First Aiders’, who I know people have gone to for issues about mental health”, says a former Wellbeing Rep. “They’ve been told, ‘Maybe work harder, so you can take your mind off it.’”

Imperial’s Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) course is accredited by MHFA England. Upon completion of the course, staff are added to the College’s MHFAiders list. Nine members of the Department of Physics are currently on the list.

Physics students reserve praise for Mery Fajardo, the department’s Disabilities Liaison Officer, who has been described as ‘the backbone of the department’. In 2013, she was awarded a Faculty of Natural Sciences Award for Support of Excellence in Teaching.

“I think in many ways, welfare in the department is held up by a couple of people”, observes Anthea MacIntosh-LaRocque, current RCSU Vice President (Welfare and Wellbeing), and former Physics Departmental Representative. “That puts a lot of pressure on those members of staff that have to deal with the concerns of all these students.”

Meanwhile, welfare representatives despair at the department’s responses to their feedback. “I feel like we’re not being taken seriously enough”, says one current Wellbeing Representative. “I became a Wellbeing Rep because I noticed that there’s a very stressful and competitive environment in Physics. A lot of people don’t really have a work-life balance, and the department doesn’t really do enough to help you with that either.”

The rep alleges that this problem has been brought up with the department at meetings, but that nothing has been done about it.

Mitigating circumstances are another topic of discontent. Students complain that there is too much bureaucracy, which leaves people who are already struggling unable to receive the consideration they need.

Alex found the evidence-gathering process required for mitigating circumstances particularly onerous. During a period when they were suffering from depressive episodes, insomnia and anxiety, they said they were put on the spot and asked pointed questions in a face-to-face meeting with the senior tutor.

Eventually, Alex was able to get support, but had to press the department in their application to defer their exams. “I know that my struggles are valid and real, but you had to make it seem like a huge deal to get the support you needed.”

MacIntosh-LaRocque says the problem extends beyond Physics, but that the department could do more to reduce the administrative burden. “Students find the process very difficult — especially since you’re already dealing with a situation that is causing you to submit these mitigating circumstances.”

The ‘guinea pig’ year

The current cohort of fourth-year students, alongside BSc students who graduated last year, feel particularly aggrieved at the actions of the department. In 2019, as these students were beginning university, the Department of Physics introduced a new syllabus.

Many feel that the rollout was conducted without sufficient planning; students described their cohort as guinea pigs. “It just doesn’t feel like they thought it through at all beforehand — they just threw it at us and hoped for the best.” One student tells us as a consequence of its sheer difficulty, the syllabus had to be revised dramatically for subsequent year groups.

An example consistently cited by fourth-year students is the ‘team-based problem solving’ (TBPS) project. First introduced for their cohort in 2021/22, TBPS is a 25-person group project, in which third-year students are asked to solve a data-based physics problem together. Half the cohort completes the module in Autumn Term, while the other half completes it in Spring Term.

Students in the ‘guinea pig’ year say that they were given very little information on the module until it began, beyond the fact that it was “some sort of group project.” Unaware of TBPS, many had selected electives in order to spread their workload across the year. They were therefore caught out when, in the first week of Autumn Term, they were told it would require a significant time commitment.

As the project unfolded, other problems began to emerge. “It became clear that it [TBPS] had not been formally structured or planned out. The department waited until students got to an obstacle, and then released more information, which made it very difficult to plan around.”

Throughout TBPS, students say they were not given enough support and had to figure everything out for themselves. The module leader, they allege, told them they would be “penalised for asking silly questions.”

Halfway into the project, students realised they were expected to use machine learning (ML) to solve the problem — despite having never been taught ML before. “It was luck of the draw whether you had someone in your group who knew ML or not”, said a former student rep.

The anger and hurt is particularly palpable in the voices of those who took the module in Autumn Term. “A lot of people got burnt out from this project,” says one student. “It made it really, really difficult to get through that first term. I developed some pretty serious mental health conditions during that time as well. In my group, we put a lot of effort into it, but by the end, we just didn’t have anything left to give.”

In summary

The responses to the TBPS project are reflective of a wider feeling amongst the so-called guinea-pig cohort, and beyond.

Across year groups, a sense persists that Imperial’s Department of Physics does not care for its students. Throughout, what seems to frustrate Physics students the most is the department’s dismissiveness and lack of understanding. “We don’t feel seen or heard by the department at all”, said one. Students talk of being “infantilised”, and “stranded” — of decisions being made for them, instead of with them. They feel “powerless”.

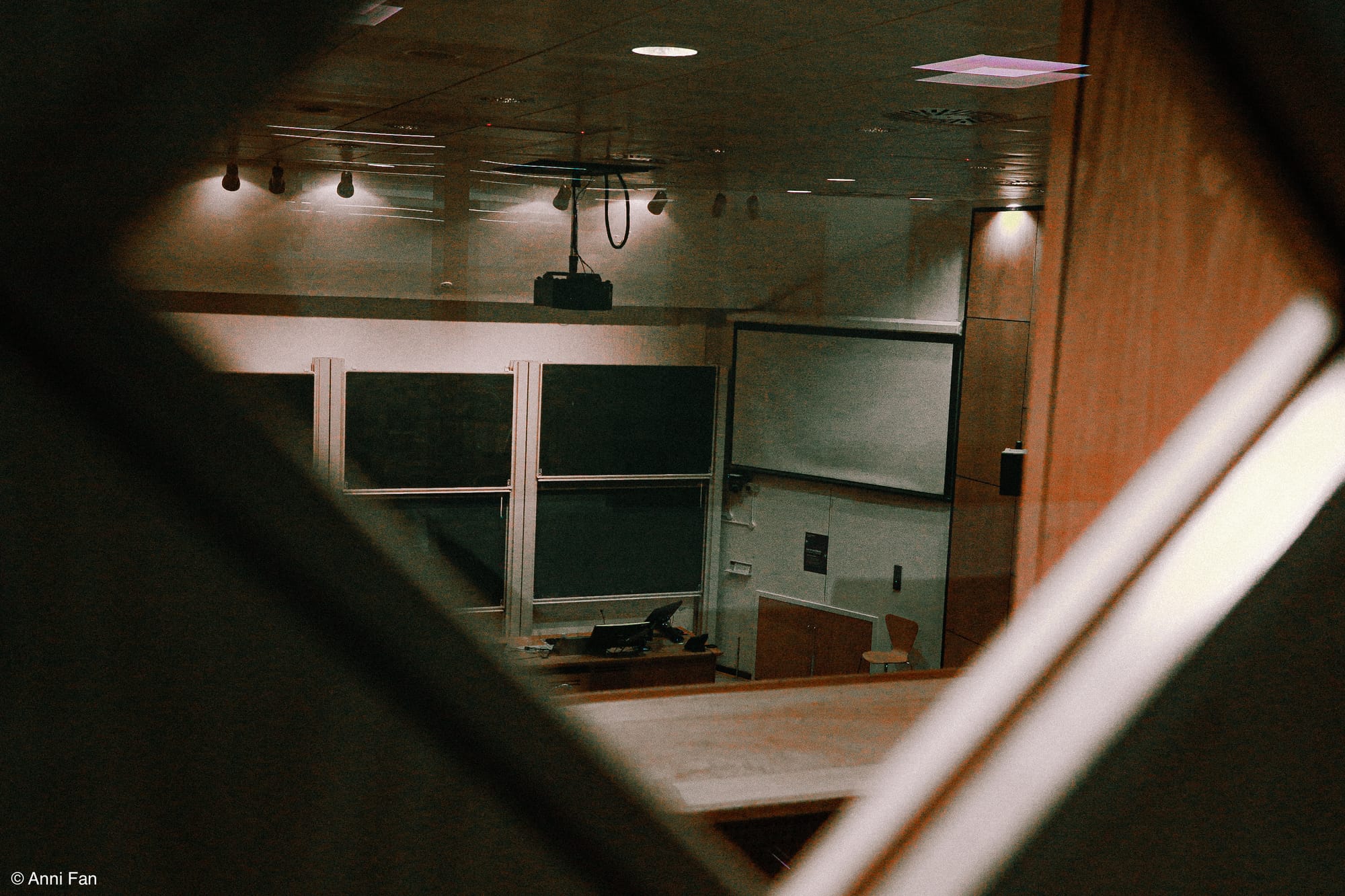

This was especially the case last year, when students say they were keen to return to in-person lectures, but the department opted to keep them online.

Physics undergraduates feel that they have tried their best to tell the department what needs improving, and convey their opinions through surveys and student representatives. Yet they see very little tangible change. “It’s really frustrating. Why are you asking me for my opinion if you’re not going to do anything about it anyway?”, asks a recent graduate.

Course representatives talk of being side-lined by the department at meetings, and feel that they are not listened to. “Rather than taking the feedback and looking at the issue, the department explains to everybody, ‘This is why we’ve done this’, instead of asking, ‘What can we actually do to fix this?’”

The lack of acknowledgement has led to disillusionment. Physics undergraduates who spoke to Felix have called the department “two-faced”, “survivalist”, and “Machiavellian”.

There is a sense that things are slowly — at a glacial pace — improving. Felix understands that over the summer of 2022, in response to its low NSS scores, the department commissioned working groups, consisting of students and staff, to try to understand the problem.

It remains to be seen what impact its future initiatives will have. But through talking to students, one thing is clear: the department’s past actions have left an indelible mark on the lives of many of the Physics undergraduates who have passed through its doors.

Alex, the student we spoke to at the beginning of this piece, was part of the guinea-pig year. They chose not to stay on for a master’s degree after their experiences at Imperial’s Department of Physics:

“Whenever things go wrong, the department just shrugs its shoulders and is like, ‘Oh well, we'll do it better next time’. And for them, that's fine because they get to have that learning curve. But for me, this affected my grades, my wellbeing and my whole experience.”

“I no longer knew why I was doing Physics. The degree had very much taken the fun out of it. I think all of us, when we started, enjoyed learning, and that was taken away from us. It was just about surviving, not really about thriving, or being excited about the subject. I had my first anxiety attack at Imperial, and mental breakdowns became a very normal part of my life. I’ve been going to therapy for a year now.”

The Department of Physics was approached for a response to this article, but declined to comment.

Correction, 25/02/2023: This article originally said, “In the 2020 National Student Survey... Imperial’s Physics department ranked bottom in the country for overall student satisfaction.” It has since been amended to reflect the fact that Imperial's Physics department was the bottom-ranked Physics department in the country for overall student satisfaction.