Sudan deserves more attention on campus.

A voice from Imperial’s Sudanese Society on the conflict, and the urgency of paying attention.

A recent Opinion piece in Middle East Eye by Anab Mohammed argued that we must rethink the way we speak about Sudan – that the country is too often treated “as a case study, not a community.” This observation struck me because it mirrors an uncomfortable dynamic I have noticed on campus: Sudan is enduring one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises, yet it rarely features in our conversations beyond the passing mention of a headline.

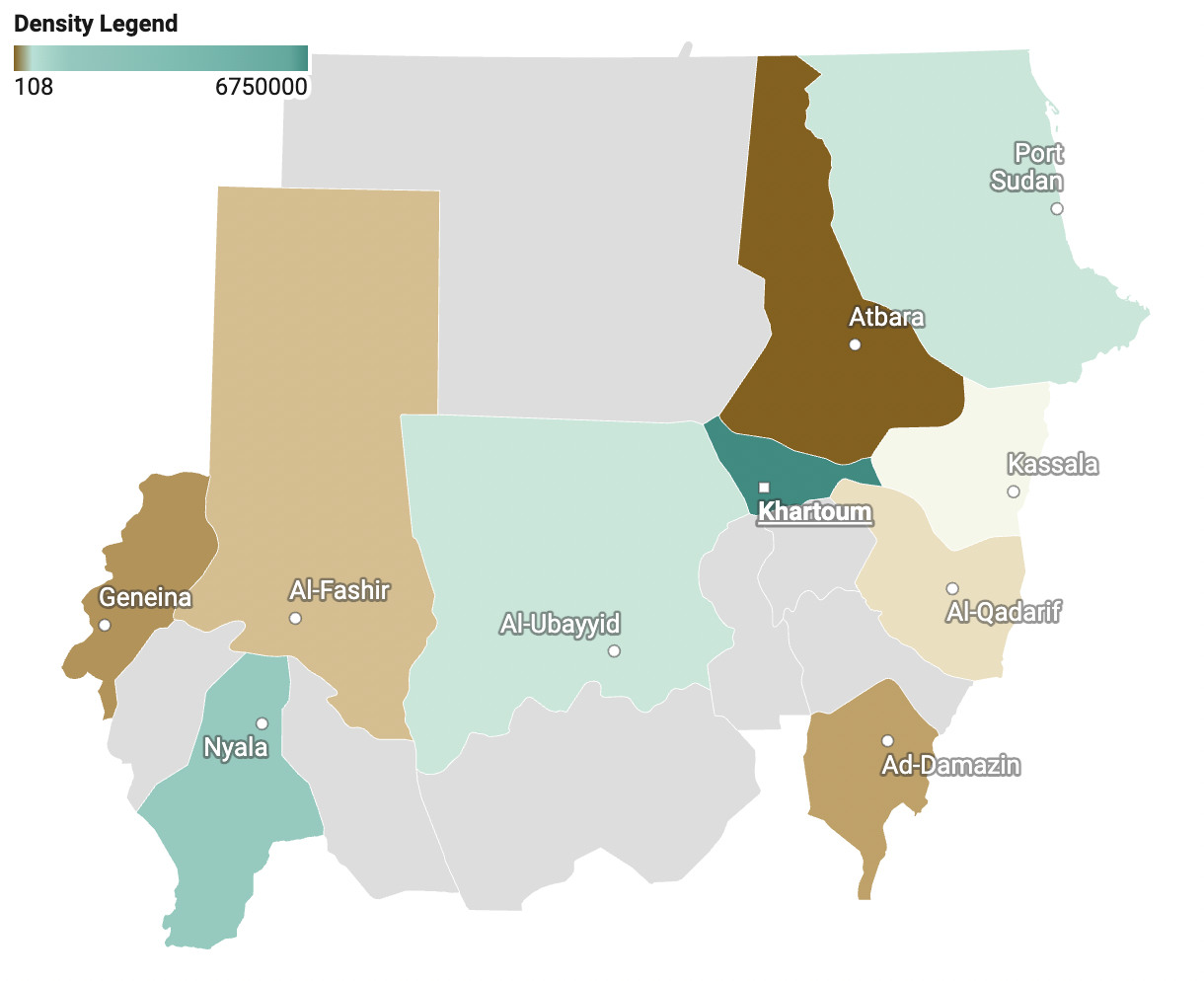

In April 2023, a violent power struggle between Sudan’s national army, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) escalated into a full-scale civil war. Fighting has devastated major cities, most recently culminating in the RSF’s capture of El Fasher after an 18-month siege marked by mass killings and the destruction of vital infrastructure. Nonetheless, despite the scale of the crisis, the war remains strangely distant in Western discourse.

Part of this distance stems from unfamiliarity. Many of us simply do not understand the conflict’s origins or why it matters. This disconnect prompted me to speak with Hiba Gorashi, President of Imperial’s Sudanese Society. I wanted to understand how the war is shaping the lives of Sudanese students at Imperial, and what a more informed and attentive response from our community and the College could look like. For those unacquainted with Sudan’s political history, hearing it directly from those connected to it feels necessary.

A conflict misrepresented – or not represented at all.

One of the most persistent misconceptions, Gorashi says, is that the war is “sudden or new.” In reality, the current fighting is rooted in decades of political instability and militarised governance. Reducing it to a generic “civil war” obscures the extreme, targeted violence inflicted on civilians and the collapse of critical infrastructure across the country.

The origins of this war trace back to Sudan’s 2019 revolution, the fall of Omar al-Bashir, and the fragile military-civilian transition that followed. Tensions between the two generals who led the 2021 coup – SAF commander Gen Abdel Fattah al Burhan and RSF leader Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo – eventually ruptured over plans to integrate the RSF into the national army, igniting the war that continues today.

As a consequence, 12 million people have been displaced, and famine now looms in the country. The siege on El Fasher, documented by researchers and humanitarian organisations, has involved mass killings, sexual violence, and systematic looting. Yet these atrocities rarely penetrate mainstream UK discourse.

“It’s not just a power struggle,” Gorashi said. “It’s a catastrophe that has pushed millions of ordinary families into displacement, hunger, and uncertainty.”

“We’re carrying a quiet heaviness.”

Gorashi described the student experience as a constant balancing act: academic commitments on one side, and the persistent weight of responsibility, grief, and uncertainty on the other. Many have family displaced, missing, or surviving day to day under siege-like conditions.

“Checking your phone after a day in university and seeing escalations of what is happening back home is devastating,” she told me. “You feel guilty for being able to turn away.”

Despite this burden, the Sudanese Society has become a space for its members to exchange updates, speak openly, and hold space for each other’s fear and exhaustion. It is also one of the few groups consistently working to raise awareness and fundraise for humanitarian relief on campus.

Paradoxically, the war has strengthened the bonds within Imperial’s Sudanese community. Students who barely knew one another a year ago now find themselves united by shared grief and collective resilience. This internal solidarity has fuelled their activism and determination to keep Sudan visible.

But Gorashi is clear: institutional support has not matched this level of grassroots mobilisation. Many students feel overlooked unless they initiate contact themselves. During moments of escalating violence, when check-ins would be most valuable, they often encounter silence.

Paying attention is not a passive act.

Gorashi’s recommendations for Imperial are neither radical nor burdensome. Instead, they require consistent and practical measures. “Being seen by the institution you study in makes a difference,” she emphasised.

Of those recommendations, Gorashi highlighted the need for proactive, compassionate outreach during significant developments in the conflict; clear, easily accessible academic mitigation routes for affected students; public recognition of Sudan’s humanitarian crisis on par with how other international disputes have been acknowledged; and practical assistance for those navigating communication blackouts or financial strain.

Beyond this, Gorashi wants non-Sudanese students to understand that Sudan is not de ned solely by its war. It is a country of extraordinary culture and resilience – one that the world has abandoned mainly in its time of greatest need.

“The world’s silence has been painful, but every act of awareness, empathy, or amplification matters.” And that is perhaps the simplest, most urgent takeaway for the rest of us. Paying attention is not symbolic; it is an act of solidarity and recognition. It is a way of saying to our Sudanese peers that their fear and perseverance are not invisible.

Imperial prides itself on being a global institution. If that claim is to mean anything, Sudan cannot remain an afterthought. The war may be unfolding far from South Kensington geographically, but for many students, it is felt every single day. The least we can do is look up, listen, and learn.