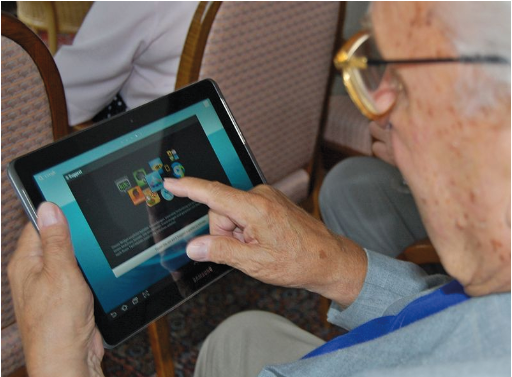

The ageist nature of technology

There is a growing need for computer and phone interfaces which account for the needs of the elderly population

In 2019, 1 in 11 were over the age of 65. By 2050, this statistic is expected to have increased to one in six. The world’s elderly population is growing exponentially, and the shifting demographics have progressively led to more and more people being left out of the modern world. The reason for this? Technology. Many of us have had the experience of teaching elderly relatives how to send a text or how to watch video on YouTube. The difficulties that they face with technology are seldom caused by their unwillingness to learn, but due to the inability to comprehend the complex task of using technological devices. The industry usually excludes 9% of the population before a product even hits the shelves, simply because using the device is far too complicated. To produce truly accessible products, companies must give users the time and aid necessary for them to come to grips with the technology they do not recognise.

Think about how you place a WhatsApp video call. For most of us, this action has become second nature. A few months ago, however, I was teaching my grandmother, and I realised how complicated it is: open WhatsApp, then go to Calls, then to the little green button that means contacts, then scroll and find the person you want to call, then press the little camera icon. This alone is a long-winded process, but it becomes more onerous when you have called the person before, then different again when you’ve messaged them before. I only ended up teaching her the first version; the rest would only create more confusion. Nevertheless, this little episode made something clear to me: all the shortcuts that exist to make using a device easier accomplish their function for many, but there is still a significant proportion for whom such shortcuts only create further complications.

Rote learning is one of the most effective methods of learning, whereby a person learns the steps of a process by continually repeating them until memorised. This is particularly true for the present generation of the elderly population, whose own education had its foundations in rote learning. Therefore, it is no surprise that this will be how they can best learn how to use technology: repeating the actions over and over until they are firmly ingrained. However, much as the physical body declines in old age, so does the ability to memorise information. 40% of over 65s suffer from age-related memory issues. While they are not always as severe as Alzheimer’s or dementia, a person’s ability to remember information is nevertheless impacted. In order to remember the process, it will take the elderly user far more than simply one attempt. However, most devices only provide instruction once, and only for the device itself. Apps provide no aid at all. If tech companies do wish to open their products up to everybody, they must be able to aid the users for as long as they need it.

There is a simple alternative to the problems caused by memorisation of a method: having a written method. This is exactly how I taught my grandmother the process of making WhatsApp calls; I wrote out each step and she carried a little piece of paper with her until she could remember it. So, while this is an obvious alternative, it poses its own problems. With 49.6% of elderly people suffering from arthritis, writing out a method on a piece of paper is almost impossible. The only clear solution to this is to have somebody else write it out for them, which, for many, is not an option. There were 3.3 million people over 70 years old living alone in 2019 in the UK, a figure which only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. While charities such as Age UK have programmes in which volunteers become “tech buddies”, this is not nearly as far-reaching as it needs to be. The best solutions which can help the elderly to get to grips with technology are available to only a very slim part of the population.

Many people, especially of my generation, will believe that this is only a problem for now; the elderly people of today did not grow up with technology, whereas we did. While this appears to be a solid argument, there are holes in it. The phenomenon of feature creep (the tendency of products to become more complicated over) means that the technology that will exist in 2080 will bear little resemblance to what we know now, ensuring that we will be just as confused as the current generation. It is easy to think that this problem will take care of itself, but it would be a mistake of the industry to go on without changing— the issue of accessibility will not be resolved without careful consideration and design

What is the solution to this problem then? Devices need to constantly be giving user’s options for the next move, thus providing them with aid for as long as they need. The lack of accessibility for elderly people cannot simply be solved by having larger text – though this is still essential. Devices need to give constant assistance to the user. But how this assistance takes place can only be decided once elderly users have been carefully observed, to see exactly how they use and prefer to use a device. Young users are frequently observed to ensure that they have the best experience of technology (with valid reason; they are the primary consumers) but it is time for tech companies to consider their whole market. Until then, technology will not be truly accessible to all.