The Chinese giant salamander

The significance of this amphibian and why its numbers are in decline

Ying-Yang literally translates to “dark and light”. It is one of the most famous symbols in the world representing the balance between two opposite poles: night and day, dark and light, evil and good, and so on. But what many people do not know is the source of inspiration behind this symbol. Surprisingly, Taoists were not inspired ancestral fights between gods or demons, or mythical kings. Instead, their source of inspiration is thought to have been two Chinese giant salamanders entwined with each other, forming a perfect circle in which the mouth of one salamander is chasing the tail of the other. However, the Chinese giant salamander can lay claim to far more than being the inspiration for the Yin-Yang symbol. It is the biggest amphibian in the world, an animal exclusive to China. It is also, unfortunately, a culinary delicacy, a fact that has put this majestic species on the brink of extinction.

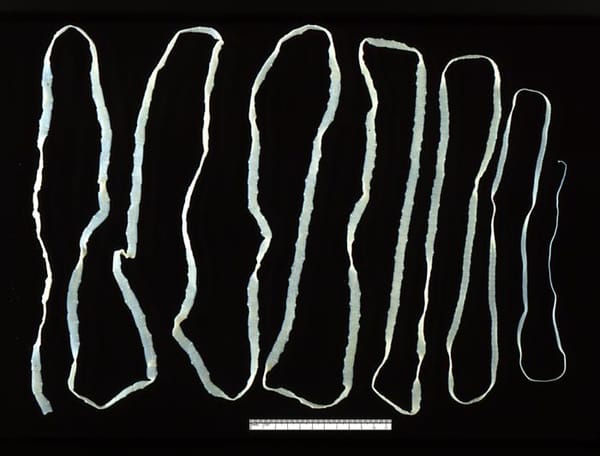

The Chinese giant salamander is native to the ponds and streams of Southwest China. It is dark brown with a flat, large body and has a broad head, with small, lidless eyes. The most incredible physical characteristic of the species is its size. Chinese giant salamanders have been known to weigh up to 60kg and to reach almost two metres in length. Fortunately, the Chinese giant salamander is generally harmless for humans. It feeds on a variety of organisms, ranging from insects and worms, to small vertebrates such as frogs and fish. Cases of cannibalism in the Chinese giant salamander have also been reported. Indeed, studies of the food in the stomach of different specimens have found body parts of other Chinese giant salamanders, compounding to around ¼ of the total food content.

The Chinese giant salamander is an extremely territorial animal, with its territory covering around 30m3 of the body of water. The only time that Chinese giant salamanders can cohabit in the same territory is during the mating period. Indeed, cohabiting is one of their courtship displays in order to demonstrate a willingness to reproduce. Other courtship displays also include activities such as riding or chasing. After copulation, the Chinese giant salamander lays a maximum of 500 eggs. This is much lower than other amphibian species, who usually lay thousands of eggs. When the larvae hatch, they possess external gills to breathe underwater. However, the adult giant salamander loses its gills, instead breathing through its skin. Contrary to many other amphibians that live both in the water and on the land, the Chinese giant salamander is exclusively an aquatic animal, spending its whole life underwater. These animals have incredibly long average lifespans, living around 60 years. There is another similarity between the Chinese giant salamander and humans: the sound. The Chinese giant salamander emits a sound similar to the cry of a child, which is why it is also called (Wáwáyú) in Mandarin Chinese, translated as ‘infant fish’. Sometimes, this creates the impression that a child is crying in the river, deceiving people.

The actions of human beings are putting the Chinese giant salamander, which has remained largely unchanged for 170 million years, at high risk of extinction. There are several factors which have played a part in this. First, the building of cities, dams, roads and other infrastructures is destroying the native habitat of the Chinese giant salamander. These large animals need a lot of space to supply them with enough food. They are also highly sensitive to pollution. Second, the Chinese giant salamander is considered a delicacy and is employed in Chinese traditional medicine. In the past, consumption levels of the Chinese giant salamander were low because most of the population was poor and hence, could not afford it. However, in modern China, individual wealth has increased significantly, meaning that now, more people can and will pay for a dish of Chinese giant salamander. This has motivated farmers to over-harvest salamanders from the wild, shrinking their population.

One potential solution is raising Chinese giant salamanders in captivity. The problem with this is that farmers take the larvae from their natural habitats instead of breeding Chinese giant salamanders themselves; breeding the salamanders is at present extremely difficult. This only exacerbates the extinction threat, since it reduces the wild population of Chinese giant salamander. Finding a solution to the breeding problem could save the entire species. Thus, more research on the reproductive mechanisms of the Chinese giant salamanders is required. To this end, the ZSL London Zoo is carrying out an important conservation programme to protect the Chinese giant salamander, while collaborating with local communities in China.

To summarise, the Chinese giant salamander is a significant part of the Chinese culture and is also a unique animal. Unfortunately, it is disappearing and we, as humans, are the culprits.