The opioid epidemic and the future of pain treatment

The roots of the opioid epidemic and their relevance to the future of analgesics

According to the WHO, opioids globally are responsible for nearly 70% of drug-related deaths, with more than 30% of opioid deaths being caused by overdose. The WHO estimates that 115,000 people a year die of opioid overdoses in the United States alone. However, despite the dire consequences, many of the strongest opioids are on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for certain diseases. Continued use of these drugs, even to treat debilitating diseases, is a major issue for the developed world. So, what is being done to resolve the problem, and what is its origin?

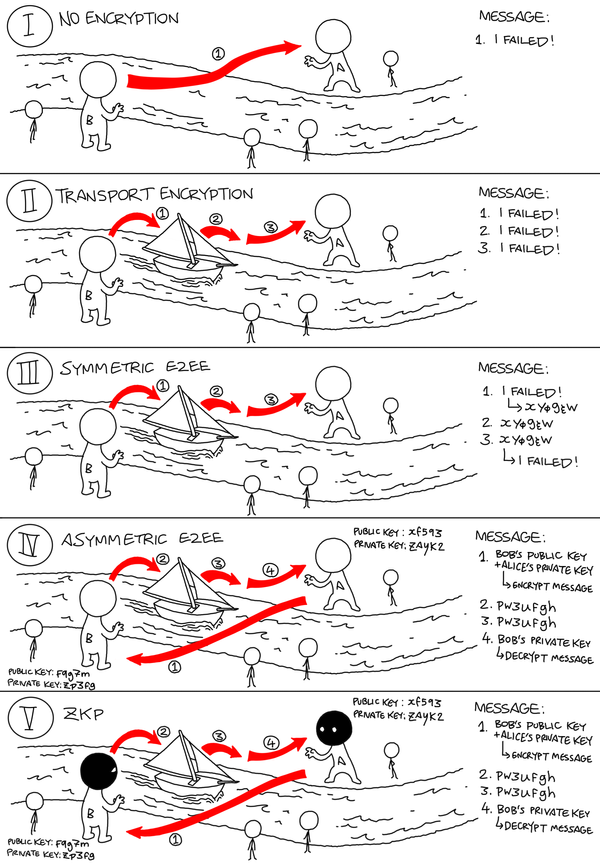

When opioids travel through the bloodstream, they can pass the blood-brain barrier and bind to a family of receptors called mu- receptors in the brain. The interaction between these receptors and opioids triggers the same feeling of pleasure received from activities such as eating, exercise and sex. This rewarding feeling can become a strong motivator for repeated use of opioids after pain has subsided. It often leads to opioid abuse.

A catalyst for this problem was that in the 1990s and early 2000s, pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed the use of opioid drugs. One of the biggest culprits was the now-discredited company Purdue Pharma, owned by the Sackler family. Purdue targeted and persuaded physicians to prescribe opioids and quickly increase their dosage, ensuring almost certain opioid addiction. This was sold to the physicians on the pretext that opioids were not addictive if taken for genuine pain. Furthermore, flimsy ‘evidence’ was provided to back up the claim. In this manner, the path to addiction was almost assured, resulting in the ongoing opioid addiction crisis. On April 2nd 2019, in something of an acknowledgement of their role, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to charges of misleading the public with their opioid marketing.

In order to try to combat the issue of opioid addiction, scientific research has expanded rapidly since the beginning of the 2010s to find alternative, non-addictive pain medications. In recent years, there have been significant research breakthroughs using a variety of approaches.

One particular methodology which is being developed involves the pH of injured tissue. A number of different types of injured tissue within the body, including muscular damage and bone fractures, have a lower pH than healthy tissue. A research group at the Zuse Institute Berlin have sought to capitalise on this with a series of compounds whose pKa (tendency to lose or gain a hydrogen atom) closely matches the expected pH levels of wounded tissues. The Institute has developed molecules that are only active in the specific pH environments associated with targeted wounded tissues. This is a common practice used in medicinal chemistry, with the inactive form of a drug being known as a ‘prodrug’.

The idea behind this is that it will prevent side effects associated with current opioid pain medications – much smaller concentrations of the active drug will be present in the body, and only at the sites of injury. This means it will not be binding to the mu-receptors in the brain; the prodrug will not be converted to an active drug in the brain, thus so long as the prodrug itself does not bind, the addictive nature of the drug should be significantly lowered. Several drugs have been shown to relieve pain by this mode of action. The efficacy of these drugs is set to be tested in clinical trials commencing in 2023.

Another approach that is showing promise involves targeting specific sodium channels within the body, vital to relaying pain to the brain. One such compound is Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ VX-548. This drug aims to selectively inhibit the NAV 1.8 receptor, which plays a key role in relaying pain signals to the brain. It is known that people with mutations in this receptor can experience extreme pain, even in the absence of injury. Blocking this receptor may prove to be an innovative alternative to opioid pain medication. However, due to its extreme similarities to other sodium channels, lots of candidates have shown dangerous side effect and toxicity profiles.

Despite these challenges, the recent clinical candidate of VX-548 is showing promise, having outperformed a placebo in phase II clinical trials. “These results are terrific, and the side effect profile is very good,” says Professor John Wood, a neurobiologist who has studied the biology behind NAV 1.8 blocking.

It is important to note that VX-548 still needs to pass phase III clinical trials and gain subsequent approval from agencies such as the FDA. This is no small step; over 40% of all drugs entering phase III trials never make it to market. Most commonly, this is because of unwanted side effects or safety concerns.

With opioids having killed many and destroyed the lives of many more, the possibility of effective alternatives taking the place of opioids is an exciting prospect. However, while the opioid problem this world is facing may soon become a thing of the past, the impact it has had on the lives of those affected will live on for decades to come.