The Times They Are a-Changing

Is the Covid-inspired launch of digital streaming for arts venues a sign of a dawning, brave new world?

Who would've thought when we stepped into the new decade that the seeds of trouble had already been sown? On December 31, the first cases of COVID-19 were officially reported in Wuhan, China. For the first time in the lives of our generation perhaps, we are faced with a situation so grave and daunting that it actually merits outrage by keyboard warriors. We have been forced to adapt and change most aspects of our lives within such a short time, from the way we consume our daily news, the way we take our examinations and of course, as is pertinent to the readers of this section, the way we look at art. By this time you have probably been bombarded by a plethora of articles about how you can still access art online. Don’t worry; this isn’t going to be one of those pieces. Rather, let us take a look at how galleries and art venues have weathered these turbulent times and what the future holds for them.

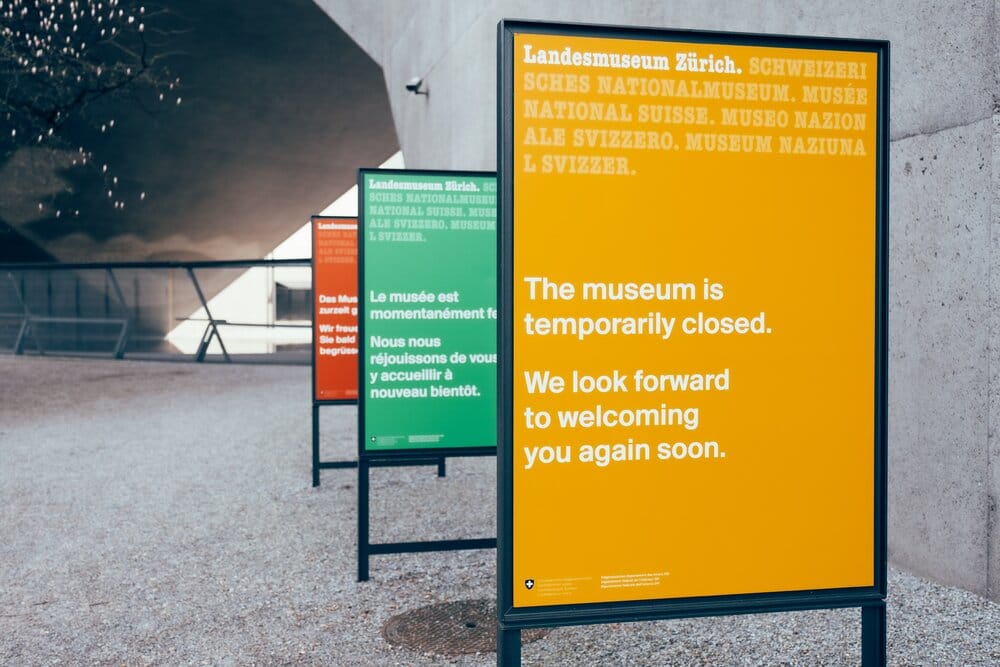

The consequences of the pandemic and the associated lockdown on art venues around the world have been severe to say the least. Shows and exhibitions that have been planned for months have had to be put on hold or outright cancelled. Take London’s art galleries as an example. The National Gallery’s much-touted exhibition on Titian has been put on hold, while a first retrospective on Cézanne’s Rock and Quarry paintings has been cancelled at the Royal Academy of Arts. Other venues in London and the world over have suffered the same fate, putting thousands of artists and administrative staff out of work. In most of these cases, postponing events is hardly a feasible solution. Cathérine Verleysen, acting general director of Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts, explained to the NYTimes earlier this week that money aside, the time-limited nature of the contracts on exhibits and insurances make postponing exhibitions unviable. With these constraints, not to mention the reduced footfall preceding the lockdown phase, there is strenuous pressure on the already fragile financial outlook of art venues and galleries. Those unable to find additional funding through endowments and donations must look to secure public funding, against all odds, to alleviate the situation.

Recent events have however shown that support for public funding for galleries and art venues is arguably low. Amidst the plight of different sectors, vying for public funds and cash infusion, the arts, typically seen as a high brow pursuit, is hardly part of such conversation. Indeed, the pandemic has only brought to fore the antiquated argument of why the pursuit of (certain) arts deserves public support and funding. In March, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts was forced to justify its request for funds from Congress. This incident is testament to the fact that the financial stability of even well endowed establishments are tenuous at best. Last week, New York’s affluent Museum of Natural History announced its plan to cut hundreds of staff due to the drop in revenue. These measures are in addition to putting full-time employees on indefinite furloughs and encouraging voluntary retirements. However, brushing aside the fact that the loss of these few months reflect a logistical nightmare and that months and years of work are probably wasted, the need to stay relevant in general public discourse and the mission to keep art accessible to the public has pushed museum curators and event organisers to look beyond this lack of support and funding and fully embrace technology as a solution.

Venues, staunchly traditional ones included, have in just weeks put together something truly amazing, bringing content online and generating engagement. In the UK, the Royal Opera House and The National Theatre have led the way in scheduling free broadcasts through YouTube and other social media channels. Museums across the world have opened the doors to their exhibits, increasing their online catalogues and removing paywalls. This transition has enabled an easier access to content and for the time being, in this locked up world, has erased geographic constraints. Yet the inevitable question is: how long can art venues sustain this online-only presence? For one, the present model of free (or in some cases freemium) online content is neither financially stable nor prudent. The regular stream of revenue from events, plays and exhibitions is invaluable to sustaining not just the venues and the artists involved but also several others who indirectly depend on this industry for their livelihood. Reruns cannot be reconciled with a purely online presence and this predicament of not being able to support workers dependent on multiple shows, as it is right now, would force the entire industry to adapt and change quickly. Another point of concern is that the online medium cannot provide curation of the same standard that a physical setting would accord.

Take for example the case of a museum curator. One of a curator’s most important responsibilities is the contextualisation of exhibits within the museum. Anyone who has been to a museum or an art gallery can vouch for the importance of this in adding to the overall experience. Indeed, artists have often competed to have their paintings placed at the appropriate location in an exhibition. The tumults between Turner and Constable to secure for their paintings prime locations in the Royal Academy exhibitions in the 19th century are legendary. Turner was adamant that his paintings 'Dido Building Carthage' and 'The Sun Rising Through Vapour' hang next to Claude’s landscapes, and included this as a clause in his bequest of the paintings to the nation. This contextual realisation of art is difficult to convey over the fickle medium of the internet and indeed has been just one of the struggles that museum curators everywhere have tried to address in this frenzied transition to an online world.

Despite everything, this transition and embracing of the 'new’ is to be acknowledged and welcomed, particularly in these uncertain times. In the midst of this pandemic a brave new world that is ever closer to technology has emerged, one that even the erstwhile holdouts, clinging to the old world and refusing to budge, can no longer ignore. Perhaps this change will lead to a wider online engagement for these venues. We could be seeing the birth of online streaming and membership for the consumption of traditional arts, or for the cynic in us, this could be a reminder that the old world is perhaps best left alone. It is true that digital experience, no matter how refined and high tech it gets, can never replace the in-person experience. However, the case for the former is enticing. Imagine a cultural world where content is truly available to all irrespective of geography, a world where we might get to see a beautiful _pas de deux_ through augmented reality right in our living rooms (albeit for a fee). With the ubiquity and permeance of technology thanks to the pandemic, such a digital life might truly not be far away. But if you are like me, aligned with the latter for now and longing for the 'real' world, then perhaps then once the lockdown lifts it is not a bad idea to visit all our favourite venues. And maybe this time, considering their predicament, we shouldn’t shy away from donating or getting a membership? After all student discounts still apply in the latter’s case - for now!