The tools for sustainable development

Imperial's Centre for Environmental Policy has helped write a guide for how the Global South can go from data to deal.

After Jim Skea’s talk, researchers from the Centre for Environmental Policy (CEP) presented their projects in Queen’s Tower Rooms. One project stood out to me – a new paper setting out a guide for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to finance a just transition and their development goals.

The paper, called Data-To-Deal: an emerging and effective approach to financing the climate transition and published on 26th January, was written by a group of researchers from Climate Compatible Growth (CCG). CCG is a research initiative funded by the UK’s Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office which includes academics from leading UK universities. Academics from Imperial involved in the report include CCG director Professor Mark Howells, CEP alumnus Hannah Luscombe, and current CEP Principal Research Fellow Dr Vivien Foster.

This research addresses a topic which is often the subject of kitchen-table debate – do we let the Global South industrialise and pollute like the Global North did, or do we stop their continued development in pursuit of climate goals? The problem is that we have no right to tell the Global South not to develop, but there may be a third option where the Global South gets to skip fossil fuels and go straight to renewables.

If this were possible, it would help put the Global South on a level playing field with the Global North, helping redefine colonial relationships which keep manufacturing and industry out of these nations. International oil and gas companies which are investing in infrastructure in these nations maintain the colonial relationship by keeping benefits to themselves.

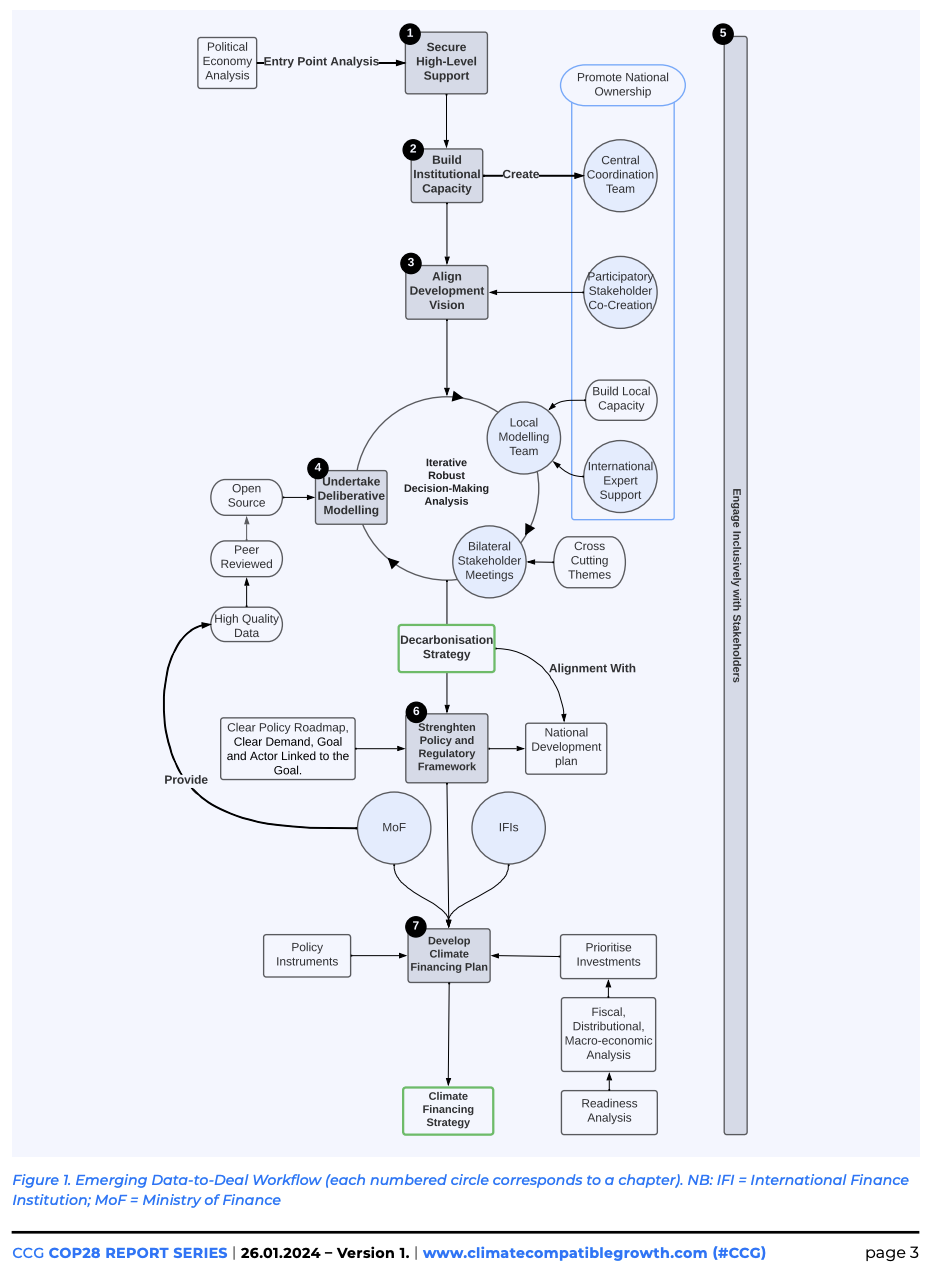

According to Dr Foster, “Data to Deal is a framework outlining the critical steps involved for LMICs to develop their own approach to planning and financing the climate transition.” The guide is the result of collaboration between 60 specialists including government officials, financiers, and academics.

The first step is about getting high-level support in government. In the case of Costa Rica, who successfully secured $2.4 billion in climate financing, this meant the president publicly and clearly commiting to decarbonisation. Engaging with the Minister of Finance is important throughout the process.

As high-level support is being garnered, a country needs to be building local capacity in universities and other stakeholders. All too often, governments receive analyses by international experts without the ability to do their own research. If data can be gathered and analysed locally, it will be higher quality. That’s not to dismiss the role of international experts, who should have input during the modelling.

Thirdly, government ministers can work with local stakeholders to align their national development vision with a climate transition. This process should help build trust through transparency and national ownership. Once complete, the vision can be shared with publicly.

At this point, everyone understands the goals of a decarbonisation strategy, which means modelling can begin to build out the details. Consulting with stakeholder groups established previously should eventually produce a decarbonisation strategy in alignment with the national development plan. This can be expanded to cover all sectors and ministries, setting out what they each need to do. This makes things clear for investors and allows the Ministry of Finance to do cost-benefit analyses. The per-sector plans allow budgeting on an individual project basis, making outcomes much clearer.

This whole plan exists to de-risk the experience for investors by making the process clear and the goals certain. All political decisions are vulnerable to changes in government, but this goes some way to producing a financing strategy based on a trustworthy decarbonisation strategy.

Costa Rica stands out as a case study, who raised their $2.4 bn from initially investing only $200,000 in this process. CCG’s goal is to take lessons from Costa Rica to other nations and encourage a similar approach. In general, they promote capacity building and the expertise required for countries to make their own evidence-based policy decisions.