USS deficit dents Imperial’s financial outlook, shows Annual Report

Heightened financial pressures make College’s sustainable staff strategy unclear

Imperial’s most recent Annual Report revealed that the College’s finances took a hit in the 2021/22 academic year as the College concluded the year with a deficit of £123.6 million, in stark contrast to the £161.7 million surplus delivered in the previous year.

The large net deficit is partially due to a projected £153.0 million increase in pension provision.

This sum — up from a £5 million contribution the previous year— comes off the back of the 2020 valuation of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS).

The USS is a centrally-administered national pension scheme for active and retired academic staff. At its latest complete actuarial valuation in March 2020, the value of the scheme’s assets was found to fall £14.1 billion short of the scheme’s technical provisions. As a result, a deficit recovery plan was put into place which obligated employers to pay a contribution of 6.2% of salaries to the fund. This will increase to 6.3% as of April 2024.

Despite the gravity of the deficit on paper, acting Chief Financial Officer Dr Tony Lawrence assured the community that in 2021/22, “Imperial delivered a sound financial performance”. Lawrence owed his optimism to the fact that employer contributions are to be repaid over an agreed recovery period of 18 years.

However, he also warned that “this is likely to remain a source of volatility in our results in the coming years”, especially as another valuation of USS is due in March.

The USS deficit recovery plan is a point of contention, as academics and academic-related staff continue to strike in protest against reforms to their pensions. Proposed reforms would see many individual’s pensions cut and employee contributions hiked, which strikers argue effectively equates to a drop in their salaries.

Prior to February’s industrial action, a spokesperson for Universities UK, on behalf of USS employers, said:

“The reality is that for some considerable time, universities have had to do more with less and make up the shortfall on the cost of teaching and support from elsewhere in budgets because fees have not kept pace with inflation. This is the context in which we would ask members of the UCU to consider whether to join the picket lines in the weeks ahead.”

Lawrence agrees, writing in the report “The cost of delivering a high-quality learning experience is increasing at a time when home undergraduate tuition fees are capped until at least 2024–25.”

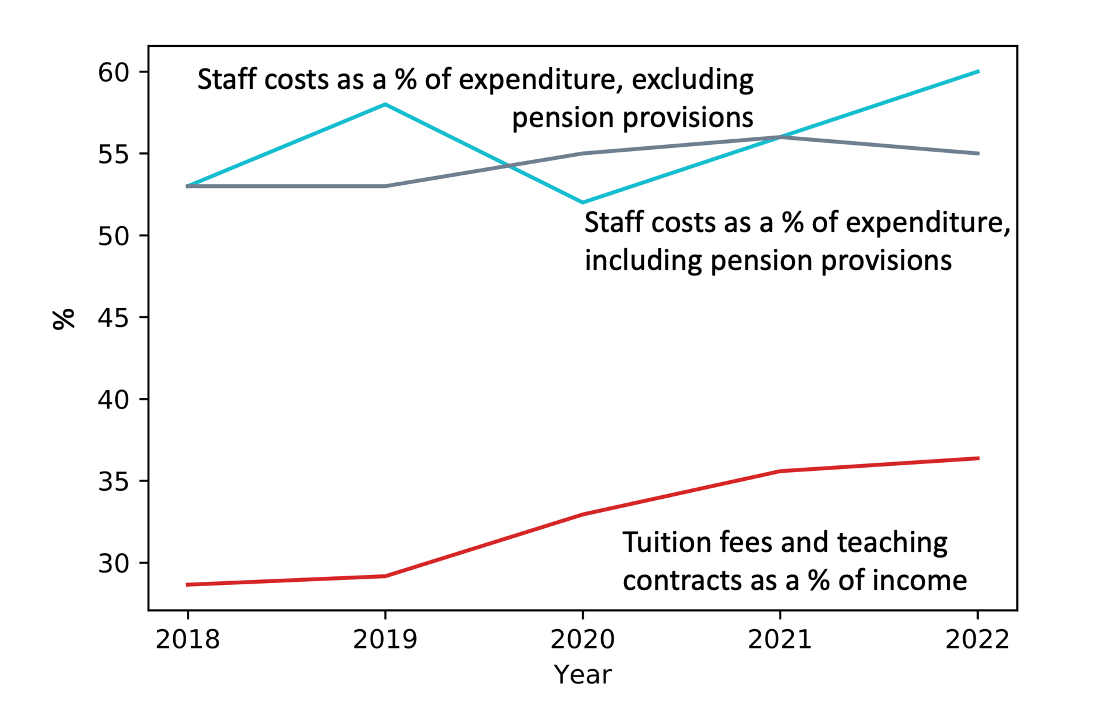

Figures from Imperial’s Annual Report show that income from tuition fees and teaching contracts continue to provide an increasing proportion of Imperial’s total income.

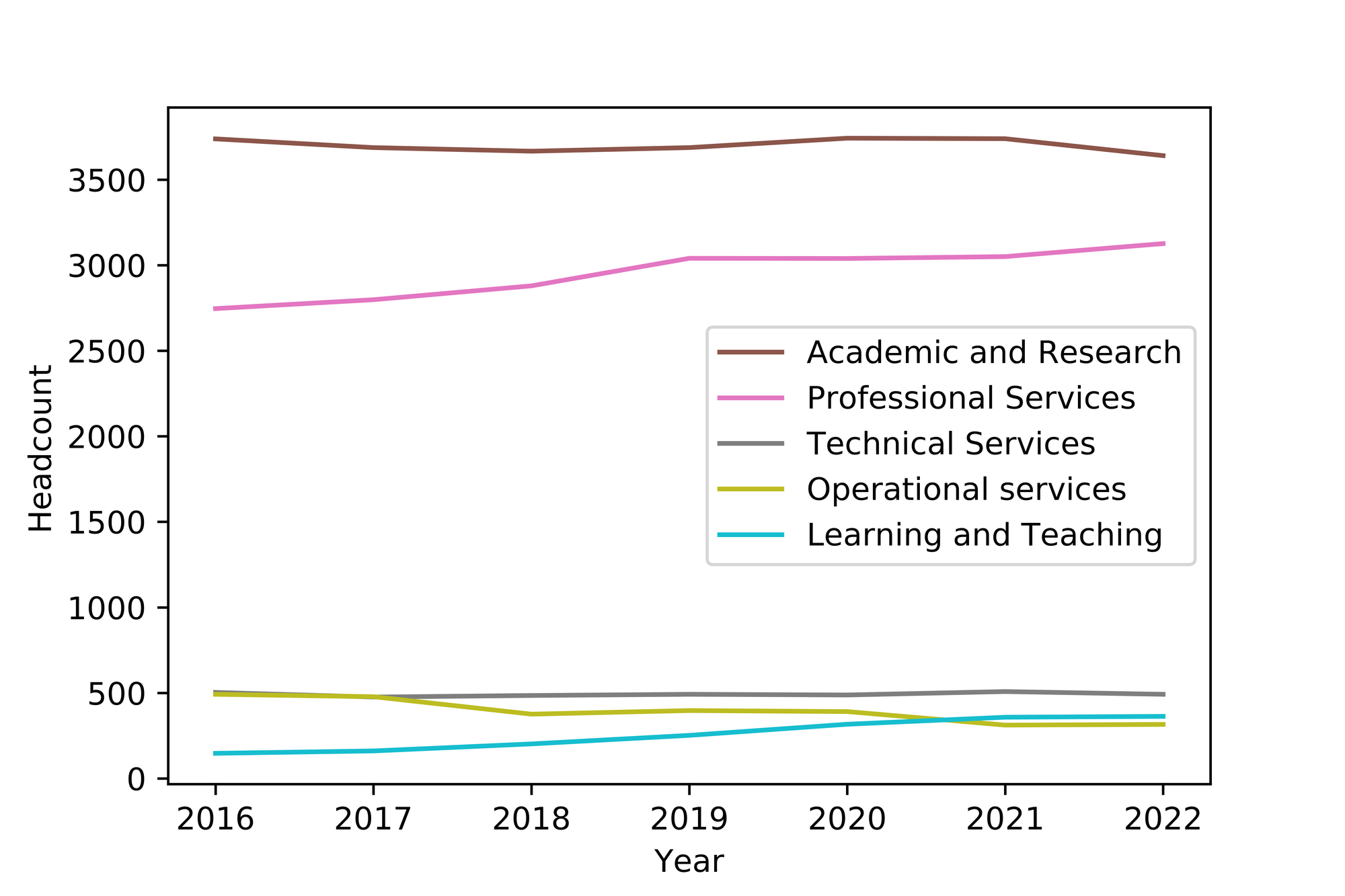

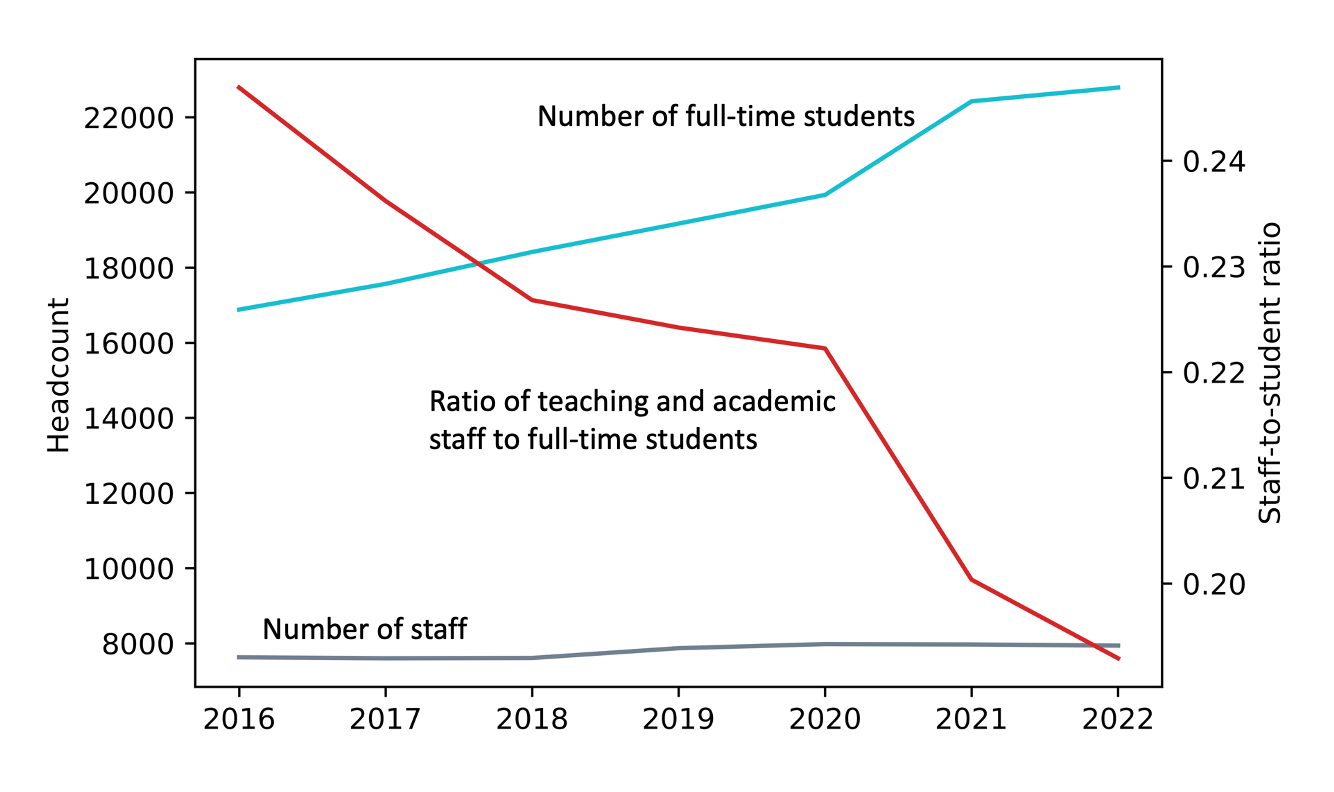

This unsurprisingly mirrors the increasing annual intake of students. Despite this, staff numbers have stagnated.

Lawrence acknowledges this is an issue, stating in the report “Overall staff numbers have stayed broadly unchanged over the last three years, despite the growth in student numbers. This is not a sustainable situation going forwards, particularly as we are planning for further modest growth in student numbers.”

However, the increasing proportion of College income eaten up by pension contributions may indicate why staff numbers have flatlined in recent years. On the other hand, the report also conceded a ‘big drop in the level of cash flow from operating activities'. Hence, the increase in pension contributions as a fraction of expenditure may simply be a corollary of the College tightening its belt in other areas.

Yet this is not unprecedented. The annual report for 2016/17 notes: “Staff numbers fell marginally in 2016/17 for the first time in five years. The fall in academic and research staff numbers mainly reflects the fact that the volume of research undertaken in Chemistry is being slightly constrained ahead of their move to new facilities in White City next year. We expect this trend to reverse in the coming years.”

However, the staff numbers have barely recovered from this low, despite student numbers having increased by just short of 30% since 2017.

Intentions for recovery may have been blighted due to the results of the prior USS valuation conducted in 2017. Similarly to now, employers were obligated to pay recovery rates of 6%, which may explain why the College was left with little capacity for growth in employee numbers since.

Relationships with support staff have been turbulent too. In January over 200 non-teaching staff went on strike in response to an offered pay rise of 3.3% which, in the face of double-figures inflation, which they deemed ‘a pay cut in real terms’.

Establishing the right balance has been on the College’s agenda for some time. In the 2016/17 annual report, the College wrote “The business plans submitted by departments this year show they appreciate the need to control cost and recognise the need to change how we provide support services. Our intention is to keep growth in support staff numbers to a minimum by redesigning our operating model.”

Lawrence hints at this redesign in the most recent report: “The increased use of a multi-mode approach blending in-person and online content is one of the ways in which we believe we are delivering a student experience that is better than ever … The hybrid ways of working we are piloting present us with the chance to rethink the way we use our space and optimise the return on our investment in our estate.”

The new People Strategy 2022+ objectives set out by the Human Resources department takes this a step further as they plan to ‘conduct a review of Professional, Technical and Operations, and Learning job families’ salary structures’. The strategy will also attempt to streamline their pool of support staff by ‘reducing the use of external agencies to increase the capacity for in-house search and create a talent pool’ and hence trim the fat on their temporary worker recruitment expenses.