Why brutalism makes people nicer

And why people who hate it suck.

If one travels to London, we often are enamoured by the large, ornate gothic and regency buildings that dot the City and Westminster, highlighting the wealth and prestige that Britain once had, centuries ago. Yet if one turns a corner, or if one happens to turn around to face what’s behind them, the result will often be a conglomeration of concrete forms: sharp, dark and jagged. London is certainly a city of contrasts in this regard, and many are often taken aback by the looming face of the 1960s against the backdrop of the 1860s.

Most often, people are revolted by the spectacle, choosing to voice their apparent disgust at how such raw forms can exist in a modern era; how we as citizens can stand idly by watching our “heritage” be overshadowed by the apparent “mistakes” of an era of depression. Those people who revile these forms often consider themselves to be high–minded – the so-called dark academic who bemoans that “we don’t make nice buildings anymore”. But such people often prefer the realms of solitude and performativism that is a gross play on Eurocentrism and classism in the modern world.

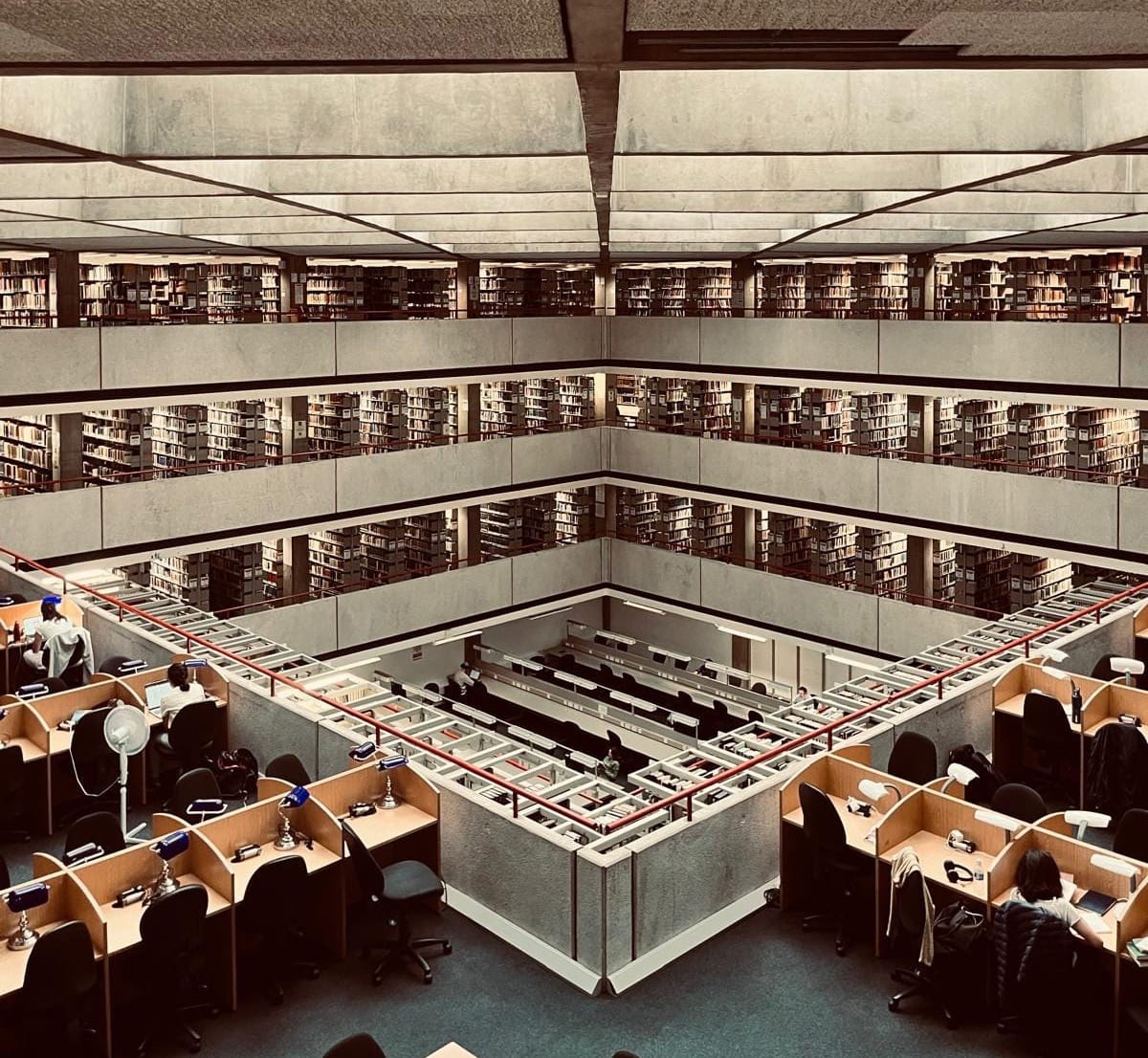

Brutalism, at its core, is a style characterised by raw forms, structural honesty, and equality of its residents, as emphasised by its leading proponents like LeCorbusier, Goldfinger, and the Smithsons. The two portions of that principle to highlight are “honesty” and “equality”. Provisions found in any Brutalist structure are large communal areas for residents, libraries, schools, and walkways, that provide the resident with a sense of intimacy and ease. This is not the claustrophobic sense of intimacy one finds in confined spaces, but an intimacy where one is compelled to be open and honest with strangers, sparking dialogue and conversation in ways you wouldn’t normally (in London, a city where impromptu dialogue is often seen as unorthodox, this feature is noticeable).

The overriding principles of equality and honesty still purvey in brutalist architecture to this day. Upon my own travels to London’s brutalist scenes, I never once felt like an imposter or out of place. Perhaps because the people who were there were so open, sparking conversation with me at every turn, and being generally – for lack of a better word – nice. The years of abuse that brutalism has faced for merely existing have created a new generation of appreciators, unbound by the shackles of pretentiousness or the holier–than–thou mindset that often makes visiting older builds colder. These people who hide in their gothic cloisters espouse the idea that they know better, and that it is brutalism that is cold and unfeeling. Why should that be, considering that my visits to the modernist scene have been the most amiable I have experienced so far?

The issue, I believe, is rooted once again in classism. The issue most people took with brutalism was the sense that it ruined “perfectly decent neighbourhoods” with its cheap aesthetic. Of course it’s cheap! It’s affordable. It existed in an era where suddenly everyone could aspire to be a homeowner, especially in the shadow of the worst global conflict the world had yet seen. The aspect that few wish to admit is that, at that time, the reason for such revile is down simply to the fact that poor people lived there; the London town–houser could scarcely bring themselves to admit that they had to have the lower–orders as neighbours.

But why should people still hold on to this outdated belief? Do people still believe that a neighbourhood of low-income citizens is inherently bad? Afterall, a Brutalist building establishes equality within its residences, provides fully functioning plumbing and heating, and has communal spaces that many would clamber for today. It is quite clearly a place for everyone from every background. To hate this style of architecture is inherently in poor-taste. To highlight the somewhat vile attitudes of the Brutalism–hater, I am reminded of when Erno Goldfinger built his modernist house in Hampstead. He received many complaints from local residents over the decision to demolish a row of Victorian cottages. It was pointed out to the authorities, however, that the cottages were dilapidated, and that there was no reason on earth why anyone would seek to preserve such useless buildings. Goldfinger won his case, but made an enemy of his new neighbour Ian Flemming, who lashed out by making him a money-loving Central–European super villain in his later work Goldfinger. Now, in retrospect, a somewhat tasteless and petty remark.

Brutalism makes people nicer because suddenly any aspect of pretentiousness is stripped away, and we are compelled to seek the higher art, not in the architecture, but in the people who inhabit the buildings, promoting dialogue, the sharing of mutual interests, and the sense of equality; whether a first homeowner or a member of the nouveau bourgeoisie, we all inhabit the same space. To the people who still look upon brutalism with disgust, you need to ask yourself why that is. Perhaps deep down you can’t stand to look at the unity and internationalism that the new world has to offer. Perhaps you only seek out lavish palaces because you yourself cannot find the interest within; your persona of frequenting dark gothic halls is nothing but a facade to make yourself seem interesting to others, when the downside to your approach is you only highlight so–called Western–European ideals. Consider this, there is one thing you can be guaranteed of when living in a Brutalist building; the plumbing works.