Curbing the decline of the Atlantic salmon

Insights into how intensive farming has harmed a Scottish delicacy.

The salmon is iconic to Scotland and any angler’s dream catch. It has been in this isle for millions of years. It has a complex life cycle, spending most of the year in the ocean before returning upriver, to where it was born, to mate. It was once prolific: in 1800 the population of wild Atlantic salmon was around 100 million, by 1950 it was 10 million, and today only 2.5 million remain. As the Earl of Shrewsbury pointed out in a recent debate on salmon conservation in the House of Lords:

“In around 1580, salmon was so prolific on English rivers that apprentices’ indentures on my family’s estate specified that they should be fed salmon on only five days of the week.”

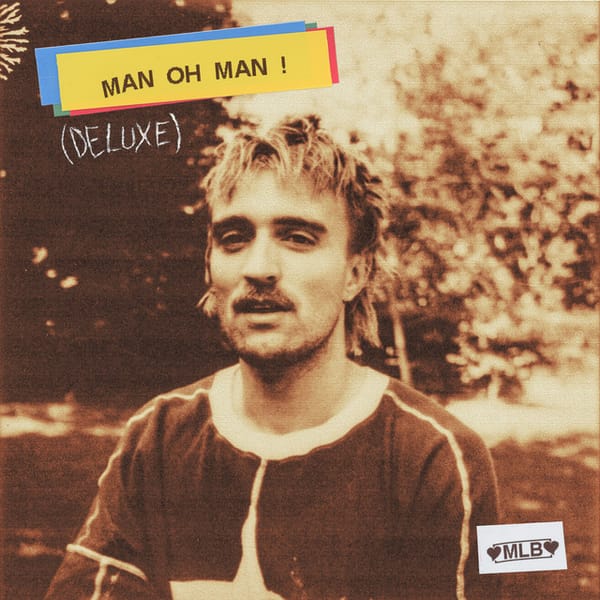

The salmon farm

This population decline has led the IUCN to declare it as an endangered species in Great Britain. The decline of the salmon was caused by overfishing during the 19th and 20th centuries. However, since 1992 sea fishing for salmon has ceased, and yet the population has continued to decline. Why? Primarily because of the harmful effects of intensive salmon farming, poor water quality, and artificial barriers damaging river habitats.

Salmon farming has been immensely harmful to wild salmon populations. Along the coast of Scotland, farmed salmon are crammed into cages. Chemicals are poured over them and antibiotics are administered to try to deal with the mass of parasites, such as sea lice, that thrive in such conditions. These parasites and chemicals greatly damage the wild salmon population and the surrounding ecosystem. These chemicals often burn through the shells of lobsters and crabs beneath the cages. In Loch Linnhe, the salmon farm was fallowed for one year, and the following season the grilse (young wild salmon) catch quadrupled.

Farmed salmon are sometimes genetically engineered (GE) and, if they escape, can gravely harm the wild population. Recently, when a GE salmon escaped from a fish farm in Iceland, there were large protests outside parliament, and frogmen were employed in rivers to catch the salmon before they bred with the domestic population.

Salmon farming need not be done in this way; in Scandinavia, it is done on land, and off the west coast of Ireland organic farms exist that do not harm the wild population or the habitat.

Protecting salmon populations

Salmon need clean, cold water. Poor water quality is a national problem affecting a plethora of species. This is caused by pollutants, be it fertiliser, manure, or peat leaching into the water.

National pressure is building on the water sector and agriculture to clean up their acts. There are also many projects designed to improve water quality in other ways such as the Riverwoods initiative who plant native vegetation along riverbanks. Not only do the trees improve water quality, but they also provide flood protection, and support for a biodiverse ecosystem, and during the summer their leaves provide to keep the water cool. River habitats are also damaged by artificial barriers and weirs which prevent migrating salmon. Builders are now often required to build salmon ladders around new weirs. However, much still needs to be done to remove old barriers that are still damaging our rivers.

For the salmon to return to its former glory, we need to end intensive salmon farming, improve water quality, and remove artificial barriers from our rivers. I encourage everyone who reads this to avoid Scottish-farmed salmon and instead substitute with trout which is delicious and far more sustainably farmed.