William Hogarth's line(s) of beauty

Tate Britain shines light on the margins of British paintings and lives of the characters painted therein

Hogarth and Europe

★★★★

- What: Exhibition

- Where: Tate Britain

- When: Until 22nd March, 2022

- Cost: £17 (Students)

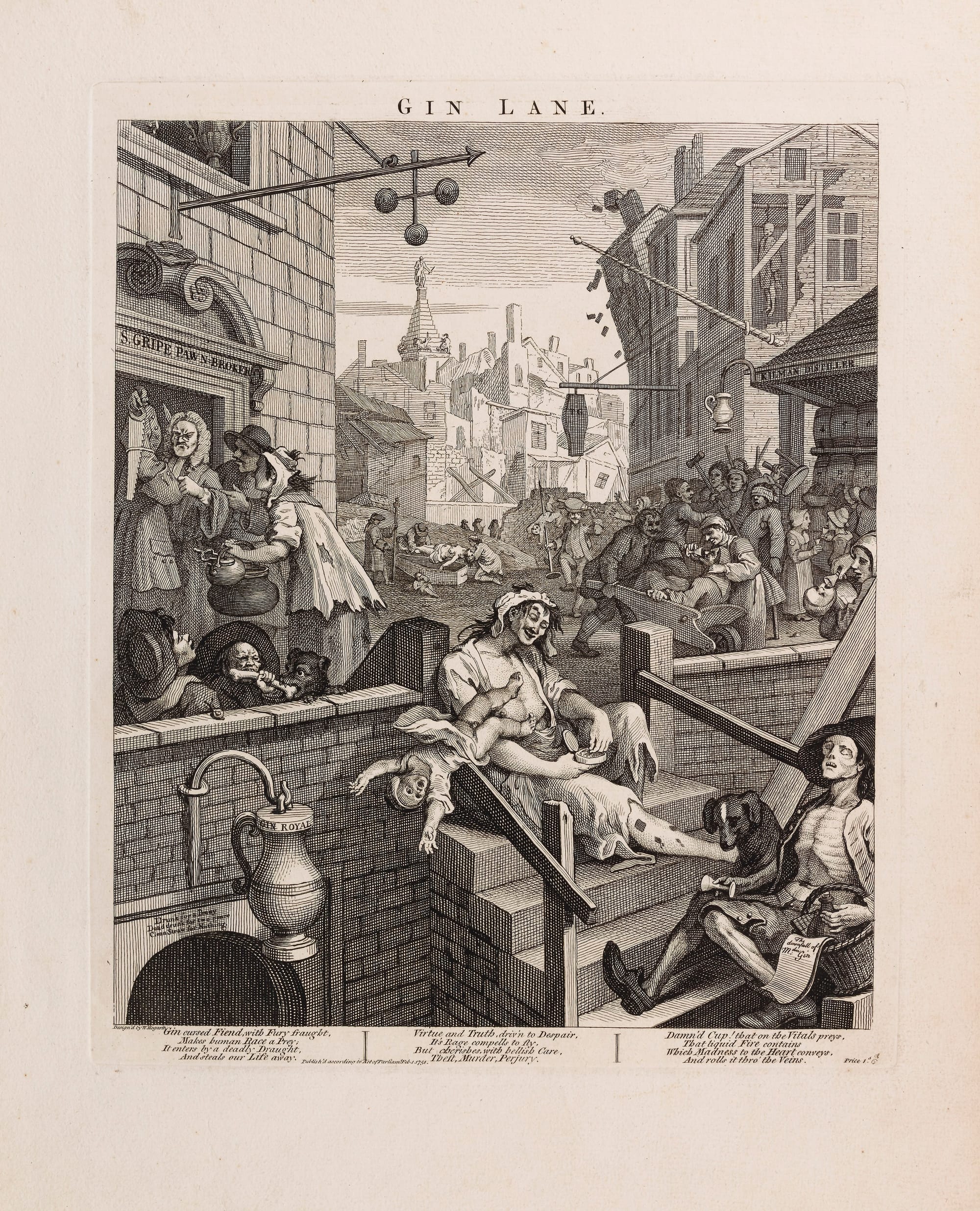

Thanks to the onset of industrialisation and revolution in engravings and print, William Hogarth rose quickly to become one of the most popular English painters of the eighteenth century. Moving away from commissioned religious work and portraiture milieu, Hogarth and his fellow compatriots across mainland Europe at the dawn of the century, instead developed through their paintings a unique commentary on contemporary social life. In short, these paintings captured on canvas the first impressions of life outside courts, reflecting instead on the common man and society. Street corners, balls, salons, and cafes became commonplace in art works slowly displacing churches and landscapes.

Tate Britain’s latest exhibition focuses on this changing tide in the mid-eighteenth century, and through a series of paintings and prints focussing mostly on Hogarth’s work, writes a dramatic telling of society as it existed then.

Much changed in eighteenth century Europe. Cities everywhere become the focus and four in particular became rallying points for gentry and artists! Venice and Amsterdam teetering on their last vestiges of the post-renaissance and trading relevance; while Paris and London were, thanks to the Age of Enlightenment and the impending industrial revolution, becoming the epicentres of the western civilisation.

In such a climate, Hogarth and his contemporaries painted not paysages, bridges and piers. Instead, we go for the first time, invited into the lives of eighteenth-century folk, and confront the vibrant city life. The exhibition opens with Hogarth’s ‘The Gate of Calais’ and this works brilliantly in two ways. For one, it presents is a striking allegory of the times we live in now, full of vibrancy and action; but also unfortunately, that of rampant stereotypes and jingoism. The fat French monk veers with ‘wry’ eyes on the roast beef of Old England (the painting’s other name), while the women around – common folk, are shown to be indifferent and succumbed to superstition. On the other hand, it sets the tone for what follows; canvases that uniquely capture city life and society, not always honestly though, but full of vibrancy nonetheless.

Speaking of cities, one sees a lot of London here. But a different London to one we’ve seen elsewhere. This isn’t the London of Turner with the hazy fumes of burning Westminster and foggy bridges; This isn’t even the London of Canaletto with the sharpness of the piers and boats striking into the cold still water. This is Hogarth’s London - one that has more in connect with Fleet Street than it does with Mall Road or the Strand.

London has never been painted with such rooted-ness. Soldiers and merry folk go about their usual lives, trysts in dimly lit pubs and street hawkers moving about their carts are more common here than any other aspect of London.

The exhibition displays the print engravings he made for the papers, praising the virtues of beer drinking whilst shunning gin and tonic (which are accompanied by some swell eighteenth century shanties). Not your average conversation among gentry, is it? Even when the paintings are of gentry or nobility — it shows a tinge of wit and self-ridicule of the characters there-in. There is more honesty in these paintings than was ever entertained before with commissioned pieces.

But if all of these are commonplace, so too are the vices and the hypocrisy of the lives these paintings portray!

Hogarth was a man and product of the eighteenth century - and even as diversity was beginning to take stock in London (Over 3% of the London population at this time were of Black heritage), Slavery and prejudice was a real and malignant presence. These aspects are found scattered across paintings of the age, but particularly in Hogarth's work. Black people, are often caricatured into stereotypes in these paintings, and stand literally on the edge of the canvas cut out of the narrative mercilessly. The exhibition does crucial justice to bring this to the forefront of discourse, dancing the fine line of allowing us to reflect sans judgement of the milieu.

In my review of Tate Britain’s previous outing with the exhibition on Turner (Turner’s Modern World - issue 1754), I alluded to quite offhandedly that 'British art does(n’t) begin and end with Turner and Constable…' It is only fair that I acknowledge here that with this single exhibition Tate Britain has shown how much more there is to it. The exhibition shows how one can learn quite a lot on social commentary through paintings and, more importantly, learn from them to be better.

This focus on social commentary can be heavy, however; and in comparison does eclipse the technical discourse on the style of Hogarth and his contemporaries — one might come out of the exhibition feeling quite like they have been to see a documentary! But again – art is storytelling, and as much as we might like, exhibitions are more about unearthing these hidden narratives than plain textbook narration. Only note that if for any reason much of the narrative explored in these paintings about the injustice of the age seems indulgent to you — you’ve more to learn than the next person! This is a one exhibition that is not to be missed!