Woolly mammoth resurrection: effective solution to climate change or flashy money magnet?

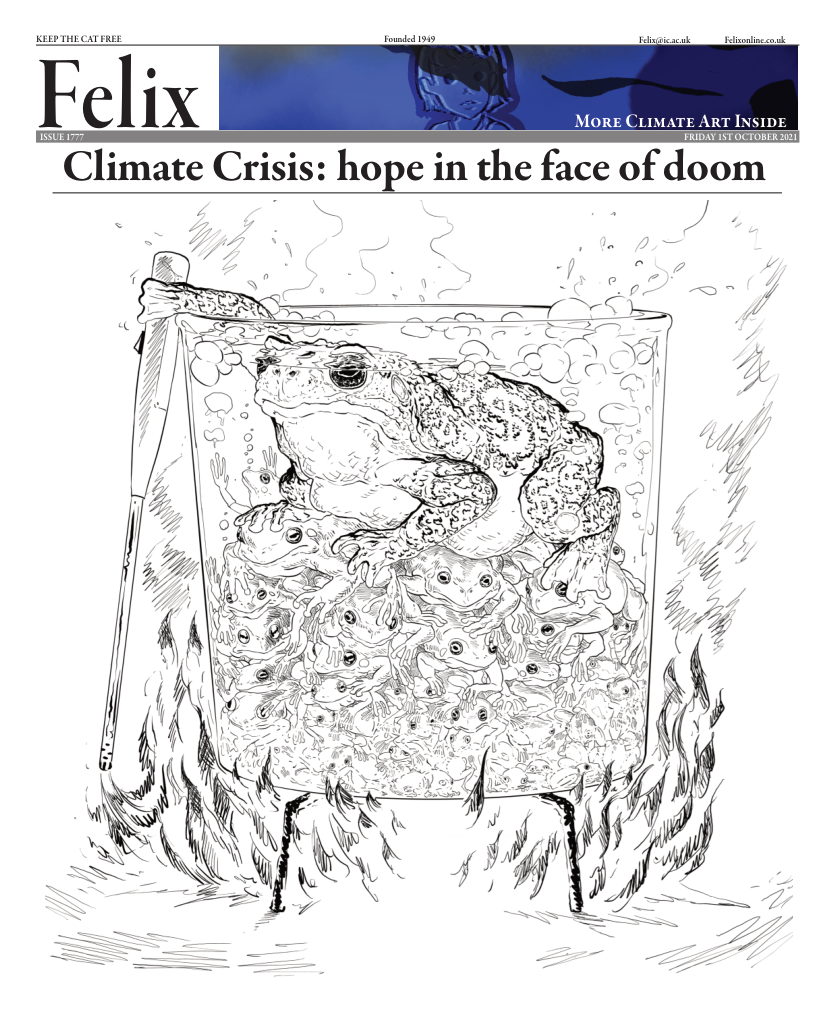

Colossal, a biotech firm, aims to bring back woolly mammoths by creating an elephant-mammoth hybrid and use it to fight climate change

While the rest of the world has been justifiably preoccupied with the burning of fossil fuels and its effect on the climate, conservationists have been trying to find innovative ways to prevent further warming of the earth and preserve earth’s biodiversity.

The news that woolly mammoths could soon be roaming among us has gripped the attention of media sources and their readers alike for the past week. Colossal, a private biotech firm, has announced the launch of a radical de-extinction project with a bold mission: to bring back woolly mammoths by creating an elephant-mammoth hybrid, and more importantly, use this hybrid to help fight climate change and improve biodiversity. Having already raised $15 million in initial funding, the start-up is confident that it will achieve its aims.

But how could bringing back an animal that became extinct 10,000 years ago work to halt the warming climate?

To answer this, we must first understand one of the potentially biggest climate change contributors that is rarely discussed – permafrost. Permafrost is simply defined as ground that has been at the temperature of 0oc or lower for two consecutive years. This frozen land makes up an expansive 24% of the Northern Hemisphere, covering vast stretches of Siberia and Alaska.

However, as you might expect in a warming climate, this ground is not staying frozen. In the last few decades, permafrost has begun to thaw, at the same time releasing just some of the 1,600 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide stored within it, as well as the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide. That is double the CO2 levels currently in the atmosphere. This process occurs when the ground temperature rises above freezing, allowing microorganisms to break down organic matter in the soil, and in the process releasing greenhouse gases. It is estimated that by the end of the century, 40% of the earth’s permafrost land will have thawed.

The idea of using large animals to protect permafrost is not new; in fact, it has already been attempted by a Russian father-and-son team, who Colossal is in collaboration with. Since 1996, Sergei and Nikita Zimov have been working on the Siberian ‘Pleistoscene Park’ where they have been bringing animals, including bison, horses, reindeer, goats, and other herbivores, to repopulate the land. 14,500 years ago, these animals used to sustain the permafrost layer as they could tramp down deep snow, allowing heat to escape from the ground and locking in the cold. Their presence also helped grasslands thrive, which takes water out of the soil and into the atmosphere, cooling the ground at the same time. When these animals disappeared from the region and moved down to Europe and Asia, they left the permafrost unprotected and vulnerable to a warming climate.

According to the Zimovs, the results of this project have been promising; the animals have adapted well to their new biome, and the scientists are noting a cooler ground temperature where the animals roam compared to the surrounding areas.

Meanwhile, Colossal has begun what the two Russian scientists have only dreamt about up until now – repopulation of the Siberian plains with woolly mammoths. Although, these animals won’t really be woolly mammoths. Colossal describes its project as ‘Woolly Mammoth De-extinction’, but the technique that the company has developed is based on the use of Asian elephants.

The team, led by Harvard’s geneticist George Church since 2017, is planning on using CRISPR to edit the genome of the endangered Asian elephant, native to the temperate climate of South and Southeast Asia. To help the animal survive in the harsh temperatures of Siberia, the scientists will edit the parts of the elephant’s genome responsible for cold resistance, such as fat insulation and hair, to replace them with mammoth genes. According to Church, Colossal’s goal is ‘to make a cold-resistant elephant’.

The benefit of using a mammoth-elephant hybrid, according to Colossal and the Zimovs, is that apart from tramping down snow, these animals should also knock down trees, recreating a steppe ecosystem that used to exist 10,000 years ago. Grass absorbs less heat than trees, and therefore the ground will heat up more slowly.

But scientists are sceptical; although the Pleistocene Park has seemingly been a success, we must understand the scale that is needed of this project. The Zimovs have been able to populate the Siberian tundra with only around 200 animals so far – a number that is too low to have a profound effect on carbon emissions.

According to Colossal, it will first take about five years before a hybrid calf would be born, and then another fourteen until it is able to reproduce. If this happens to be a success, the company will need to breed enough elephant-mammoths to repopulate 3 million km2 of Russian land in order to prevent a significant amount of greenhouse gases from being released. To many conservationists and climate scientists, this feat seems improbable, if not impossible.

There are other hurdles Colossal has yet to face; the first one is getting the Russian government to agree to the use of a vast amount of land by an American business. Then, according to conservationists, bringing back a population of animals that has been extinct for thousands of years is risky, as we cannot understand how they will be able to adapt and fit into the biome.

Finally, many scientists have voiced the opinion that vast amounts of money and resources are being misdirected. Instead of spending millions on an idea that has a low probability of being successful, they claim that it would instead be more useful to direct that money to de-extinction project that we already know will work.

For example, conservationists have recently joined efforts to work on a programme that will breed coral reefs to make them more heat resistant. Coral reefs - the ecosystem with the highest biodiversity on earth - directly supports the livelihood of over 500 million people worldwide. It is paramount that we protect them now, as according to UNESCO, coral reefs in all reef-containing World Heritage sites could cease to exist by the end of the century. This is why, to many climate scientists and conservationists, a project that will only begin to work in 20 years does not seem like a wise target for 15 million dollars of funding.

If we are to avoid the most severe outcomes of climate change, we must limit global average rise in temperature to 2oC. This would require global greenhouse gas emissions to be cut by 60% by 2050. To truly make a difference to the rate of global warming, we simply need to focus on the obvious solution – moving our economy away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy sources. We simply can’t afford to wait and see if a miracle mammoth project is going to save the planet; we must do it ourselves, and we must do it now.