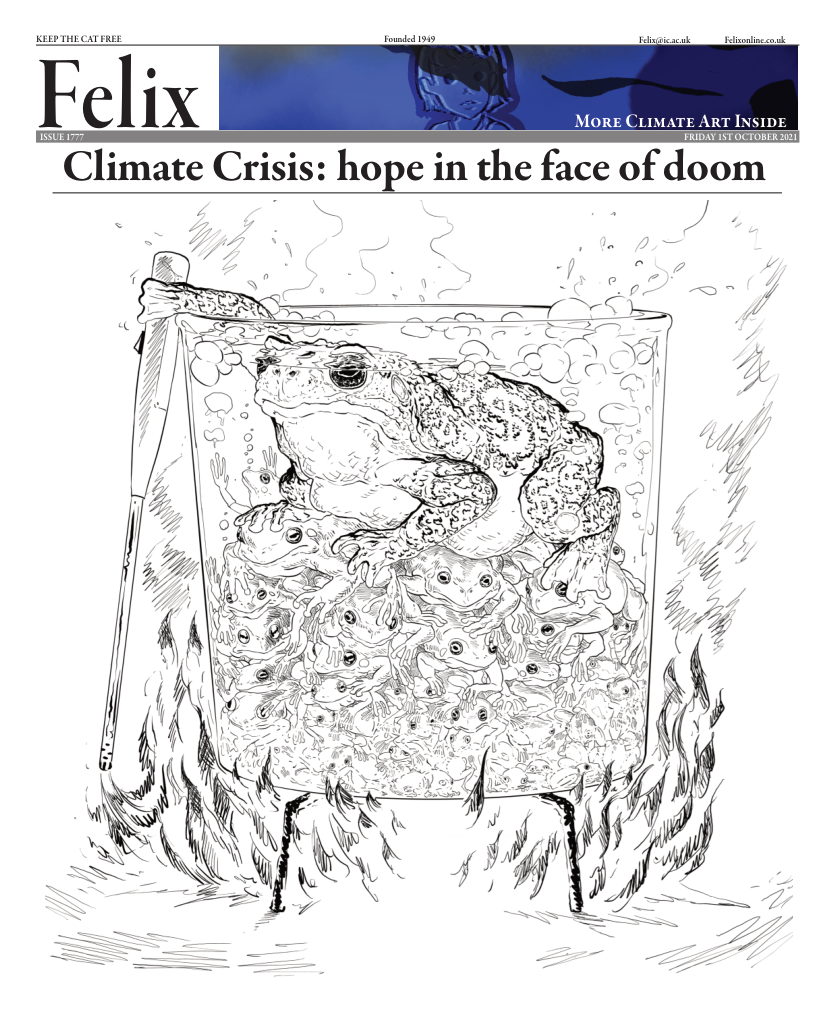

Reflecting on climate change - A rural Zimbabwean perspective

Comment editor Khama Gunde sits down with her mum to discuss how climate change has impacted their rural community over the past few decades

“We all share one planet and are one humanity; there is no escaping this reality.”

- Wangari Maathai

The 2021 IPCC climate report made it clear that there is no region on Earth that has been left untouched by climate change. Though, by now, it should be well known that climate change is exacerbating social inequalities within and across countries. For example, the World Bank’s 2021 Groundswell report stated that if no actions are taken, approximately 216 million people could become ‘internal climate migrants’ by 2050. Particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, and South Asia.

We need to continue listening to the experts, scientists, and activists who have been arduously educating us. However, I am concerned about the people whose voices are not heard, especially those who do not have the luxury of viewing the climate crisis as a topic of debate.

As someone who has spent most of their life in the United Kingdom, I have always had access to information regarding global warming, climate change and environmentalism. So, for me, the impending climate crisis has always been on the periphery. Despite this, I rarely felt a sense of urgency or fear and my lifestyle has hardly been affected. This is a privilege I would not have known had I not immigrated to the UK.

In December 2019 my family and I went on a three-week trip ‘back home’. ‘Back home’ meant an 11-hour flight down to the southern hemisphere, deep into the southern regions of Africa to my birth country of Zimbabwe. The last time I was there was August 2011. The passage of time meant I had lost the rose-tinted lenses of childish youth. Now, Zimbabwe is a country which has a plethora of social, economic, and political problems, but it was the environmental changes lurking in the background that left me with a lingering feeling of hopelessness.

The first day we drove past the corn fields on my maternal Grandparents’ farm, I immediately noticed the crops were not as lush as I had expected; crops that had the potential to rival my height barely met my waist. In the moment, I brushed my concern aside – instead I attributed what I saw to the fact that my Grandparents were getting older, and so of course the upkeep had been slipping. Only later, through a conversation with my mother and Grandmother did I naively realise that the suffering crops were part of a concerning trend beyond their control.

We never heard of that growing up. It would rain and rain, but we never heard of a 'flood' happening.

So, I decided to sit down, interview, and listen to my mother. Over a long phone call, she painted an image of a beautiful rural landscape that has, over time, been beaten down by harsh heat, sporadic rains, and unexpected weather events.

What was the farm like in your youth?

We were used to heavy rains during every rainy season growing up. In fact, we had what we’d call ‘bumper harvests’ – where we’d harvest huge amounts of crops each year.

We used to sell our produce to the Grain Marketing Board, and we’d have tonnes of sweetcorn for sale every year. At once stage the equivalent of the BBC, the Zimbabwean broadcasting corporation, came to take a video of our farm to show on TV. At that time the land was all green and lush. There was a river that ran along the farm that used to be flowing and full of water all year round.

That river is now non-existent. It has been dry for years, decades.

On rainy seasons, after the rain we would go with buckets to fields parallel to the farm. We would catch fish because they’d be swimming up the river but on the ground. My siblings and I would be catching fish with hands and putting them in buckets.

We would watch migrating birds from Europe as they would follow the rainy belt. The birds would be ahead of rain, so that’s how we would know the rains were coming - like when they talk about pressure system on the TV. We used to call them ‘stork birds’, those white birds. When we saw lots of them we would know rain is coming.

So, we used to plant all our crops the same time each year, plough the fields, put seeds in ground, weeks before the rain and the rain would come approximately the same time each year. So, seeds would germinate, and crops would grow until harvest time.

Were there difficult times?

Drought came, I remember, two times. One time was in the 80s and cows died. The cows would try to drink water in marshlands and would get stuck. A few died since there was no grass and not enough water. We had boreholes – one for irrigation and one for drinking. They have never dried up; they have been there since before I was born. In the 90s, the drinking borehole began depleting, but it still sustained the village community (including teachers and students from my school). People would come to fetch water as early as 4am, because their supplies dried up. By 6am, it would be a little muddy but still drinkable – not contaminated, it has always been safe. To this day that borehole has been sustaining lives.

One particular drought year there wasn’t much to eat, some days we would just have maize meal porridge with sugar. But there would be no food to eat afterschool, maybe a cup of water with two or three spoons of sugar for lunch in the afternoon. So, from the previous years’ harvest we had preserved maizemeal which we kept for porridge and sadza (a staple food in Zimbabwe made from maize flour and water). Breakfast would be porridge with sugar and peanut butter, or tea with bread. Supper would be sadza with vegetables or small fish. Beef maybe once a week and chicken was on an occasion, Easter or Christmas.

Vegetables weren’t doing so well in the garden, during the drought, they died from the sun, scorched really, and lack of water. Some nights we would roast dry sweetcorn kernels to make maputi (a very popular corn snack). Some nights, dried sweet potatoes. In Zim, the staple food is sadza – with vegetables or meat of any kind. We were lucky, your grandma had planted some sweet potatoes prior to the drought, which sustained us for most supper nights.

When did you start noticing changes?

We would have very hot spells during the hot season, then it would rain with thunder and lightning in broad daylight, I knew some who died in those storms. We would get hailstones as well.

One rainy season, the weather started changing – it had become sporadic. It had been hot for quite some weeks after planting seeds and earlier rains. Seeds came out, but rain would come back at certain stages to nourish seedlings. The rain would leave for weeks on end, and so crops suffered. Then it would rain hailstones and heavy rain that shredded the cabbage leaves and tomatoes. So, the ground was soaked but one time it proved to be a miracle, because when the rain went and sun came - we got giant cabbages and tomatoes! It was as if the soil was fertilised. We’d eat cabbage and tomatoes in salad during a season when it didn’t rain as much as it should have. It used to rain from September to March. By December we would have sweetcorn to eat, cook, and roast.

From late 90s it has been changing.

Wait, it was supposed to be rainy while we were on holiday? It was 30 degrees almost every day!

It would have been pouring, but it was just scorching hot. It used to rain all night, we would wake up and it would be wet outside. There was nothing in the gardens during December 2019. It would have been muddy and rainy all month. In fact, we used to pray for sun on Christmas. Nowadays it’s just hot all December, with maybe some rain around April, rain is sporadic now.

Around April time we would harvest the crops, this would fit into school holidays each year. In recent years, it pours in March - which is when the produce should be drying. Between September and December, the rain disappears. Sometimes, when the rain appears, it just pours and drowns the crops.

You remember, don’t you? That it only rained one time when we were there and, even then, the ground dried up on the same day.

The river that used to run along the farm is gone. When it rains it doesn’t fill up.

How do all the changes make you feel?

It makes me feel sad.

How have people’s lives changed over the years?

Some fruits don’t grow as they used to. Especially the wild fruits that would be in abundance and available for people to pick during droughts.

Also, having three meals a day has been a luxury for some since the 90s. Tea and bread for breakfast is a Western thing. Traditionally we have porridge or sweet potatoes, with tea. Lunch is whatever produce you harvested during the previous year. People keep their food in storage equivalent to a pantry. So, you could have a year’s supply of dried peanuts, dried sweetcorn, dried Round nuts, dried chickpeas, dried soyabeans, sweet and normal potatoes, or pumpkins. This food was supposed to sustain households throughout the dry season and the following year.

My family used to grow loads of crops. Cotton, sunflowers, rice - in fact we used to eat organic brown rice and process it ourselves. We would also make our own peanut butter.

Why don’t they grow a variety anymore?

Water levels have gone down, the rainy season changed so some crops are not grown anymore. Sekuru (Shona word for Grandfather) loved farming. When I was younger, he set up irrigation pipes and would line up seeds with string on a straight line. He used cows to plough the land and then would go put the seeds in. We used to have equipment to cover the seeds and cultivate the weeds. Irrigation pipes stretched all the way from the fields to the borehole, where someone would be pumping, and on the other end someone would be watering with pipes. That system stopped because the borehole supply started getting low. So, we started relying more on rain but that wasn’t reliable for irrigation either.

Are rural people noticing these trends?

They’ve noticed but some think that maybe next year they can do something different, or something will change. Even though for some years they’ve had less produce.

Could you say more on what it is like now?

There have been floods now, and we never used to have them. Chimanimani had a terrible flood in 2019, during Cyclone Idai. Schools were evacuated and people died.

I remember at the beginning of the millennium there was a terrible flood. If I recall, in 2000 there was a cyclone, I never used to hear of this before. People had their houses washed away and people died. We never heard of that growing up. It would rain and rain, but we never heard of a ‘flood’ happening. What makes it worse is that most people in rural areas build houses with mud walls and grass rooves. These houses crumbled and were easily washed away.

Another thing, we used to apply cow dung to fertilise the soil, but when the weather started changing and it didn’t rain as much, the manure in the ground would ‘burn’ the crops and damage the produce.

When we went back home, the grass was just dry. Some days, Grandma’s pumpkin leaves around the yard would look withered. Growing up, we used to be able to sit in the sun, but we can’t do that anymore - the sun is too hot. When we were there in December you noticed how everyone would sit in the shade, didn’t you? Yet growing up you could work in the fields in the heat. In fact, we never used to have temperatures like 30 degrees unless it was drought. The temperature would be 20-something if it was sunny, which was comfortably hot because you could walk and work in that heat.

What do you think should be done?

We need to go out there and talk about climate change, make people aware of it. Let them know that what they’re facing is actually climate change, let them know what is contributing to it around the globe and in Zim. Zimbabweans need to go out there, talk to and lobby the non-corrupt MPs to try to bring some change. Lots of factors are contributing globally, Zim is obviously contributing too – for example we have many unroadworthy cars, and millions of unfit buses on the roads.

There’s not much production there because of the economic situation, so I think the main problem is cars that are not roadworthy. There is no MOT system over there so anything with four wheels can be on the road. That needs to change because anyone and everyone has a car there. The government needs to introduce viable public transport; and renewable sources of energy need to be prioritised. We need trains to connect people between Harare and Marondera instead of hundreds of car trips. There needs to be development in Zim. People are okay getting on with their day-to-day lives, but they may not be aware they’re contributing to climate change.

Some people are ignorant, and they aren’t thinking about their great grandchildren and future generations. They’re just thinking of the now.

My mother’s account is sobering but, sadly, millions across the world are facing harsher experiences than she did. They do not get to escape the reality of the climate crisis like some do.