Science Gallery: Spare Parts Review

For those unfamiliar with the new Science Gallery at London Bridge, the project was conceived as an international network of public engagement spaces established in partnership with major local academic institutions. The first opened in Trinity College, Dublin, and currently, there are four such galleries, with two due to open in 2020 in Melbourne and Venice. Science Gallery London is the most recent offering, opening in September 2018 in collaboration with King’s College London. Following the inaugural Hooked exhibition about addiction and recovery, Science Gallery London set its sights on the future with Spare Parts, an exploration of human repair through a “collision of artistic and scientific disciplines”. Within the gallery’s three floors, the collection of artefacts invites you to explore the body of tomorrow and what it means to be human within a framework of rapid technological progression.

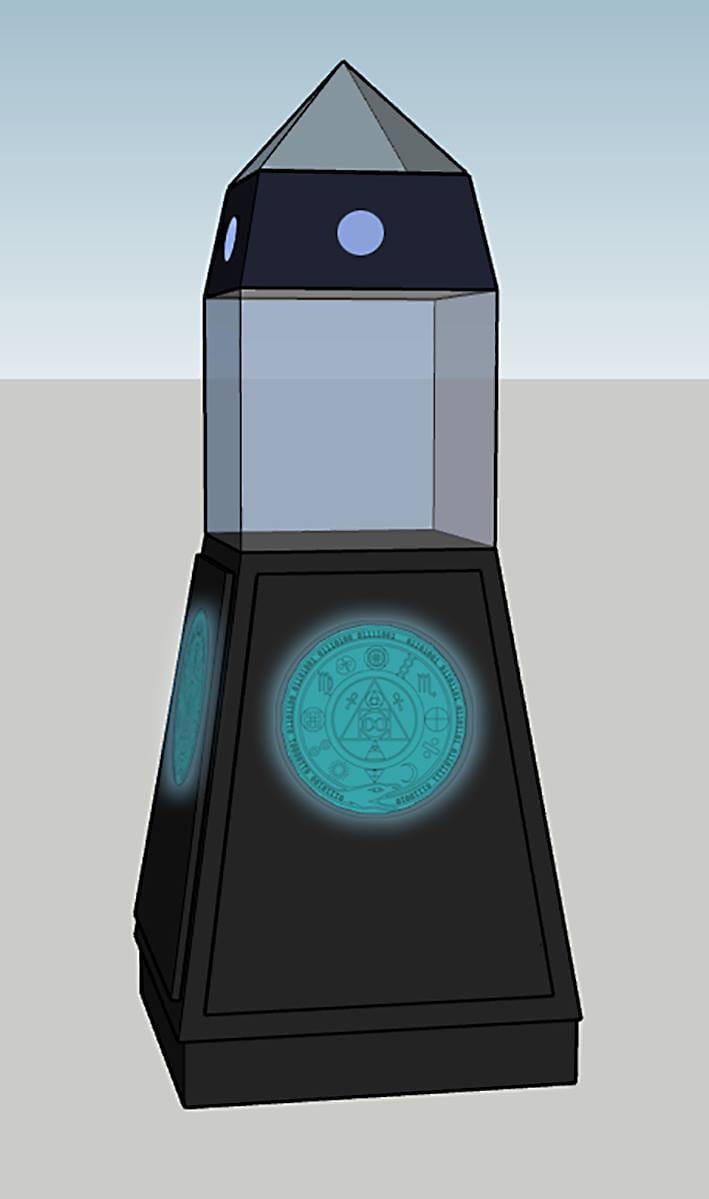

Collision is a more fitting description than maybe the organisers planned on as the collection is a rather chaotic mix of art, science, and philosophical ideas thrown together with varying outcomes and degrees of success. Guarding the entrance to the exhibition, Kratz, Hart, and Hutmacher’s Monument to Immortality is one of those pieces that manages to strike a balance in all three areas and asks the question, “How much do we value control over our mortality, and how far are we willing to go to achieve it?”. A man-sized Cleopatra’s Needle with a Whovian makeover, the black structure showcases historical and alchemical symbols pertaining to immortality and mankind’s attempts to reach it. The centre houses a bioreactor filled with body-part scaffolds and seeded with cells. Panels live-stream close-up footage of the bioreactor and at the very apex, a hologram shines like a beacon. A tad overwrought? Maybe. A potential set piece for Indiana Jones in Space? Definitely. But as a rare collaboration between two new media artists and a world leader in the field of regenerative medicine and biofabrication, it makes its point and makes it well. Another highlight was the interactive prosthesis electrode designing station in the “Gut”, a workshop space designed for ideas to be ruminated upon and digested.

Unfortunately, some collisions produce a rather more confusing result. Burton Nitta’s New Organs of Creation shows a real-life larynx being constructed in an incubator surrounded by models of synthetic larynxes inspired by cats, koalas and a man with a record-breaking deep voice. It’s a visually striking piece of art that’s unnecessarily complicated by an odd opera side project and overambitious political goals. Somehow, as the mediator patiently tried to explain, the artwork aims to explore stem cell research, culture divides, digital audio manipulation, and even the healing of Brexit-induced national divides in some sort of conceptual rollercoaster ride. Reeling from the ideological whiplash, I was then faced with the theatrically named Microbiome Rebirth Incubator, a jumbo-sized apparatus complete with an indeterminate bubbling liquid. One could almost imagine this being a mail-order chemistry set for budding alchemy giants if I wasn’t then told that the potion being concocted was actually a vaginal and breastmilk culture. The Microbiome Rebirth Incubator isn’t just an art piece, it’s a device actually intended to allow mothers to “seed” their caesarean-born children with vaginal bacteria, like a baptism with Group B strep. Apart from addressing relatively little about the exhibit’s main focus of human repair (unless the implication is that babies born via caesarean section are somehow damaged), this creation seems much more intended for a museum, or preferably Goop’s next expo. As part of the installation, they even created a private baby-feeding space in the gallery where you can listen to experiences of giving birth around the world. While I laud their inclusivity, I also can’t help but wonder how many new mothers are rocking up to an exhibition about transhumanism located on a college campus with their babies, and indeed how many wanted to watch a vat of vaginal flora gently bubbling away while they breast fed.

Spare Parts is a frustrating exhibition because its premise is fertile grounds for cross-discipline collaboration but a lack of direction meant it was difficult to view the exhibition as a cohesive narrative. One also gets the sense that there were struggles identifying the exhibition’s target audience. Scientists and academics may find that the some of the more science-focused pieces lack the complexity and nuance posed by real-life medical or biological problems, while others may find the collection missing the mass-appeal that this sort of exhibition could achieve. That said, there are some genuinely exciting artworks in the Spare Parts exhibition and I am very much looking forward to Science Gallery London’s next exhibition, Dark Matter, due to open in May.

Spare Parts runs from 28 February to 12 May at the Science Gallery. Entry is free.

-3 stars