The dark side of democracy

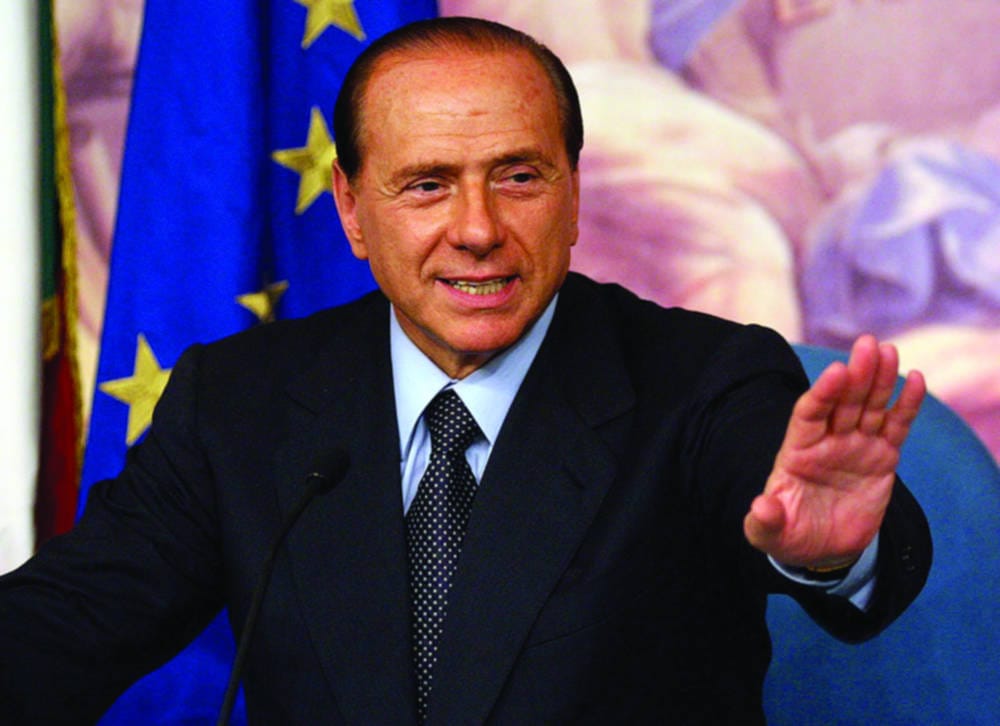

Pietro Aronica takes a look at the downfall of Berlusconi

The reign of the tyrant is over. In Italy, people celebrated in the streets as Berlusconi resigned; across Europe, markets sighed in relief and hoped that his successor would be able to unscrew the pooch that he so thoroughly enjoyed screwing. The ‘it has to get worse before it can get better’ part of this financial crisis seemed to be behind us, and Italy could get back on the road to normalcy. Times, finally, are looking up.

It’s easy to forget why we got here, why Berlusconi was allowed in the control room for so long. There is very little doubt that he was a terrible leader and a pretty reproachable human being to boot. So how could this man have been allowed such a heavy influence in the politics of the eighth largest economy in the world for close to twenty years? Simply put, he was elected. On three separate occasions, the majority of voters looked at this man and thought that, yes, that was the guy they wanted to run their country.

Arguably, Berlusconi is amongst the greatest failures that democracy has ever produced, rivalled only by the stint by a terrorist organisation in Palestine (and that time which cannot be mentioned without invoking Godwin’s Law). He’s living proof that you don’t need sparkling ideas to convince a nation that you should lead them; a charismatic demeanour and a truckload of money to spare will suffice. He was hailed as a media genius, as someone who spoke to the common man and handled information in a modern way. He was given far too much credit. Berlusconi simply managed to play the system.

Of course he looks like a media genius: he directly controlled three of the six main channels of Italian television (which exist only to propagate his message), alongside some of the most influential newspapers and magazines of the country. His stranglehold was almost total, and he made sure that it was only his views which got across to the general populace. He named his first party “Hooray for Italy!”, which is about as uncultured as it gets, and he won on the back of the “revolutionary” slogan “Less Taxes For Everybody” – second only to “More Money For Everybody” in the ranking of inanely populist catchphrases.

Arguably, Berlusconi is amongst the greatest failures that democracy has ever produced

Berlusconi has always been portrayed as an anomaly. An outlier, a freak occurrence. But the truth is that democracy will always be prone to these sorts of hiccups. On paper, democracy ensures that the best course of action is undertaken, because the people, who bear the consequences of those actions, get to choose; in practice, people are a cowardly and superstitious lot who rarely bother to research or care about the election. Elections, as Berlusconi showed, can become little more than popularity contests, with candidates winning simply because they have the tightest grip on the information channels, and are thus able to sway public opinion. It is not political creed or ability to govern that put people in charge, but the ability to control the media.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating for some revolution to destroy the system; I would just like to point out that democracy, often seen as the gold standard of governments and hailed as the solution that, if implemented, will singlehandedly lead to the prosperity of a nation, is deeply flawed. As with many ideas that are great in theory, it relies on assumptions that simply aren’t true: in this case, that the general public is a reasoning, rational beast which always makes the most intelligent choices for the future.

Democracy, as it is evolving, works better than other systems but is in danger of falling in disrepair due to complacency on our part. Serious laws on conflict of interest and greater emphasis towards technocracy would be desirable in order to avoid a populist drift of the institutions. Most importantly, we need to reconsider the way in which we, the public, approach it. Holding as the ultimate authority the opinion of a population who may or may not be informed on the issue at hand and are easily swayed by the media is an idea that deserves very careful scrutiny.

Italy’s latest mistake cost them fifteen years of missed progress and is threatening to collapse the euro; we must acknowledge, and prepare for the fact, that vox populi doesn’t equate to vox dei.