Rusty fungi genome gets a polish off

Another step towards food security

In a pioneering step towards achieving food security a team of American and French scientists, including members from Harvard and the University of Minnesota, have unveiled the first sequenced rust fungi genomes.

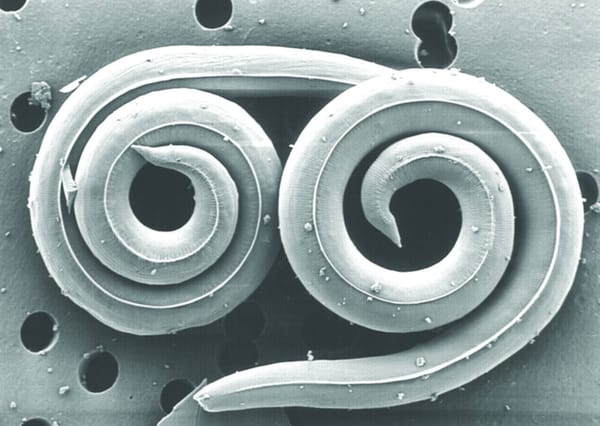

Rust fungi infect the cells of their host plants, taking nutrients from the plant and causing losses in yield that are often devastating to a harvest. Selective breeding and genetic engineering have created many rust resistant varieties of the crops we use today but the rust evolves quickly and there are strains we have not been able to control. The scientists hope that unravelling the genomes of the poplar leaf rust fungus (Melampsora larici-populina) and wheat stem rust fungus (Puccinia graminis) will lead to more successful attempts to control these strains which are damaging both economically and in terms of biofuel production and food security.

Wheat stem rust has long been a threat to food security. The fungus can reproduce asexually in the wheat plant during the whole summer, producing spores that can spread over vast distances in a single year. Infected plants suffer from a reduced yield and, if severe, can result in an early death. The effect on the food production of a country can be devastating. So much so, that in the 1950s the US developed a biological bomb designed to spread wheat stem rust and cause havoc in the infected country.

Poplar leaf rust threatens the use of fast growing poplar trees as biofuel as well their value in the wood industry. The rust fungus affects the general health of the trees, limiting their growth and resulting in a reduced profit for the plantation.

The team of scientists have predicted several proteins similar to known proteins in other pathogens. Some of these are expected to be involved in the actual infection of the plant and the way in which the fungi enter the cells. Others are transport proteins which enable the fungi to steal nutrients from their hosts. There are, however, some missing proteins which suggest the reasons that the fungi rely on their hosts is related to them being unable to take up some nutrients in the forms found outside the plants. This also partly explains why the rust fungi could not be grown in vitro in the lab, a challenge that the team had to overcome during the project.

One of the great successes of the Green Revolution was the development of rust resistant wheat varieties. Currently, a new, highly virulent strain, Ug99, threatens global wheat production, particularly in many African countries. The identification of proteins resulting from the genome sequencing will aid understanding of the way in which the rust fungi infect their hosts, obtain nutrients from them, and overcome plant defences. This will in turn help to develop new resistant strains of wheat and poplar plants and restore yield levels.