Catching a wave

Physicists perform direct measurement of photon wavefunction

Physicists have come one step closer to unveiling the elusive quantum world with a new experimental method developed by Canadian scientists. The article, published in Nature, shows how a team from the National Research Council of Canada Institute for National Measurement Standards were able to perform a direct measurement of the wavefunction of a photon, which is the elementary unit, or ‘quanta’, of light.

The wavefunction is central to quantum theory and is a complex distribution which completely describes a quantum system. In contrast to everyday experience where the state of an object, such as its position or momentum, can be precisely determined, things become fuzzier in the quantum world. Particles can be here or there, and Schrodinger’s cat can be dead or alive. The Catch-22 (until now, at least) was that by attempting to measure a quantum object, its wavefunction would ‘collapse’ to a new value and then evolve as a different wavefunction. Jeff S. Lundeen, one of the authors of the paper, comments, “A feature of the wavefunction is that, unlike a water wave, the very act of observing it changes it, making it a slippery object to measure.”

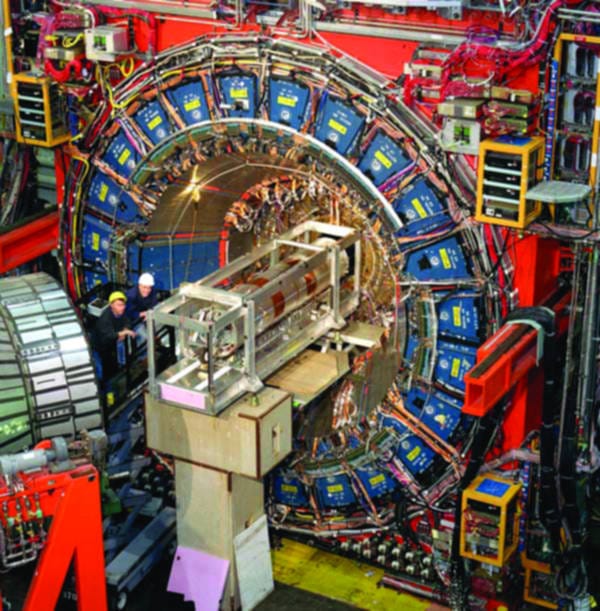

The team were able to circumvent this problem by performing two complementary measurements of a photon in succession; one ‘weak measurement’ which is gentle so as not to disturb the wavefunction, followed by a second normal (or ‘strong’) measurement. Although the weak measurement lacks precision, accuracy can be regained by averaging over many measurements.

In the experiment, individual photons were generated by attentuating laser beams. The position of the photons were weakly measured through measuring their polarisation. A lens was then used to select for photons of a given momentum.

Another intriguing aspect of the experiment is how the imaginary components of quantum numbers can be made manifest. Observables from strong measurements are real numbers while the mathematics requires that weak measurements can have real and imaginary components. Both the real and imaginary numbers can be realised in the dial of an apparatus: the real component determines the position of a pointer, while the imaginary component determines the momentum kick. This new method for observing the quantum world will be vital to fields as diverse as quantum information and drug discovery.