Tackling Cystic Fibrosis

Ned Yoxall talks to Dr Jane Davies on new advances in CF treatment

In June this year, the Cystic Fibrosis Gene Therapy Consortium started a ground breaking new trial looking at the effects of regularly dosing sufferers with gene therapy. Ned Yoxall speaks to Dr Jane Davies, the clinical lead investigator in London, to find out more.

Ned Yoxall: Thanks so much for agreeing to meet! Could you tell me a little about your background – how did you end up in cystic fibrosis (CF) research?

Dr Jane Davies: It’s a bit of a random story! I went to medical school in Dundee before coming to London where I did a series of paediatric clinical jobs with a particular interest in infectious diseases. Before long I found myself at the Royal Brompton doing a respiratory and cardiac job, and this is where I had my first contact with CF patients. The CF lung is full of infection, so I ended up doing an M.D. looking at how bacteria stick onto the epithelial cells. After a spell at Great Ormond Street, I came back to this job – a combination of a clinical consultant and an academic – where I’ve been for the last 12 years.

NY: Could you give me a brief dummy’s overview of what CF does to the body?

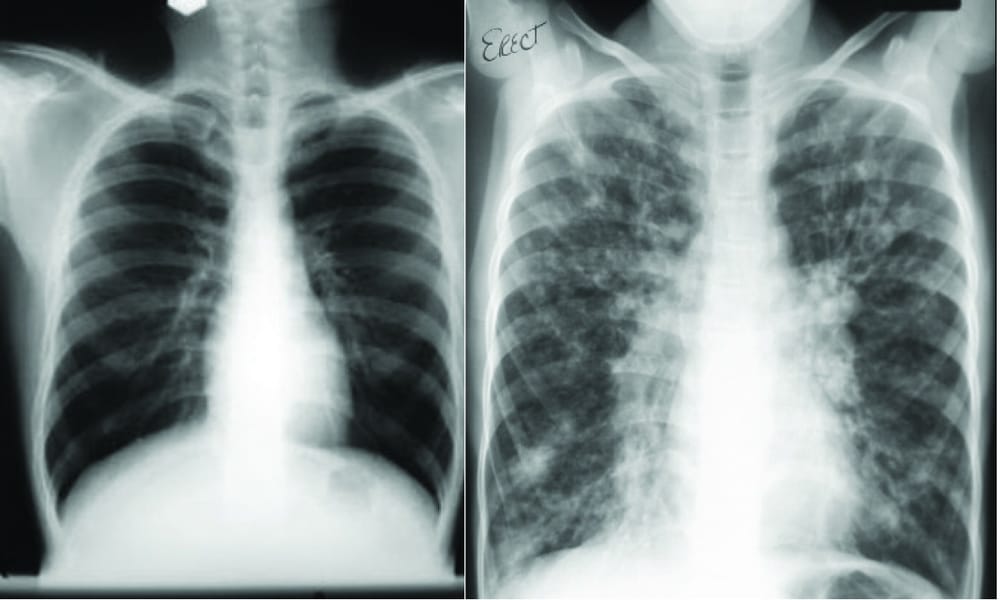

JD: CF is a genetically inherited disease, so if a patient has two copies of the abnormal gene then the cells lining the organs of their body don’t handle salt well. The mishandling of the salt leads to dehydration of the surface secretions – particularly in the lungs – so they become dry and sticky. They then act as a very attractive place for bugs and viruses entering the body. This triggers an inflammatory response, but the infection is never properly cleared, so you enter a vicious cycle of chronic infection and inflammation which leads to tissue damage and other difficulties.

Our approach uses synthetic liposome-based vectors to deliver DNA

NY: So what’s it like to live with CF?

JD: Well I don’t know that first hand, so no matter how well I know my patients I can never pretend to know exactly how they feel. It is certainly very difficult both practically and psychologically though. Practically, a huge amount has to be done every day to manage the disease – up to an hour a day of physiotherapy to clear mucous from the lungs, as well as nebuliser treatments and between ten and twenty different pills to be taken. That’s when things are going well, and almost all patients go through episodes where they need to be in hospital for several weeks at a time. Psychologically, it’s completely relentless and it’s something that you know will be with you for the rest of your life and you know that your life will be considerably shortened – life expectancy is in the late thirties at the moment.

CF is physically exhausting; psychologically it’s completely relentless

NY: What is the Gene Therapy Consortium, and what’s it trying to do?

JD: It’s an amalgamation of three individual groups – Imperial, Oxford and Edinburgh – which had previously been working in competition, but were brought together by the Cystic Fibrosis Trust to work in collaboration. The aim was to bring a step change in gene therapy trials where success would be measured by how patients actually felt or performed after treatment rather than by molecular markers in the lab.

NY: Has gene therapy been attempted in the past?

JD: Yes – for lots of different diseases. It’s been really successful at treating some cancers and immunodeficiency disorders, but gene therapy trials for CF have never been big enough or long enough to look for clinical benefits before now.

NY: What makes it so difficult to achieve?

JD: Lots of gene therapy approaches use a virus to carry the experimental gene into the cells. Viruses can be quite good at this and for some diseases it works really well as one viral “hit” can be a treatment for life. The problem with cystic fibrosis is that you need to treat the lungs, which constantly renew themselves, so you can’t easily target a stem cell – you need to give the treatment repeatedly, and unfortunately the viruses are targeted by the body’s immune system. So although you can get excellent gene transfer the first time, by the third or fourth time, with most viruses at least, it drops to nothing.

NY: What’s different about your approach now?

JD: We’re not using viruses to carry genes into the cells. Instead we’re using synthetic vectors based on liposomes which fuse with the fatty cell wall and allow the new DNA to get into the nucleus. This process is almost certainly less efficient than using viruses, but you can do it repeatedly.

NY: What’s the best case scenario after this trial?

JD: The best case scenario would be a highly significant increase in the lung function of those having undergone gene therapy. This would be the first evidence that the approach works with CF and it would then be taken forward with a collaborating pharmaceutical partner to develop a treatment.

NY: And the worst?

JD: That it doesn’t work at all. While this would be disappointing, we do have a second wave using a different approach, which in fact is a very unusual virus that can be given repeatedly. A negative trial certainly wouldn’t mean the end of gene therapy for CF.

NY: What does the trial mean for people with CF?

JD: Well I’m very careful not to use the word cure. Even if it is successful, it will still need to be given repeatedly and will only treat the lungs, not the other organs which are affected. It could, however, be a major move forward and so there is a lot of optimism about it.

Ned completed Ironman Wales back in September to raise money for the Cystic Fibrosis Trust. You can sponsor him online by visiting www.justgiving.com/NedsIronman or by text through JustTextGiving by sending ‘IRON66 £(amount you’d like to give)’ to 70070. Anything you can spare is hugely appreciated!