A cheaper way to make hydrogen

A faster way to fill up on the horizon

A promising way to power vehicles and appliances in the future is through use of hydrogen fuel cells. These, however, require a source of hydrogen to work, and obtaining this hydrogen has typically been an expensive process.

The most common method to obtain the gas is to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. This is an operation that requires a catalyst, and the catalyst must be such that it reduces the energy necessary for the reaction to occur as much as possible. The lower the energy that is required, the more efficient the system, because it means there is more energy left over to actually power your system. Hence, platinum catalysts are often used due to their excellent catalytic ability.

A problem with platinum, however, is its ever-rising cost: something that has been seen with many rare metals as their availability becomes ever reduced. Hence, alternatives involving cheaper catalysts are needed, and researchers at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York have developed a promising candidate.

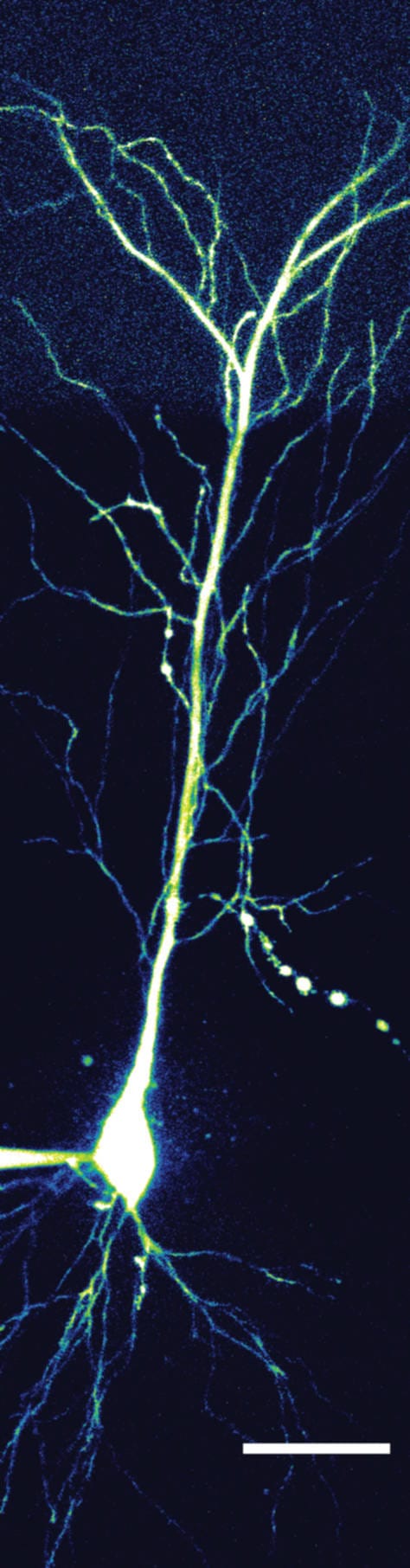

One of the best features about platinum is its high electron density. A cheaper catalyst, nickel, does not have such a high density, though this can be alleviated somewhat using molybdenum. This alloy still, however, will not produce the required level of catalytic ability. A proposed solution was to add nitrogen to alter the electronic state of the alloy, which has been proven to work in the macroscale. In the nanoscale, it was found that applying nitrogen via exposure to an ammonium environment caused 2D nanosheets to form. These sheets have a greater catalytic ability thanks to the increased surface area, and hence the mixture has a catalytic ability similar to that of platinum, but with a reduced cost.

As well as providing a cheaper yet effective method to produce hydrogen, this research is significant for seeing the production of nanosheets, when only nanoparticles were expected. As nanosheets have an increased surface area (and thus increased availability of reactive sites), this may lead to developing even faster catalysts using other materials. In the aim to produce synthetic catalysts as fast as natural enzymes, such improvements are always welcome.