Quadruple DNA? Go home DNA, you’re drunk

Philippa Skett thinks DNA are now causing a scene and need to be sent home in a taxi

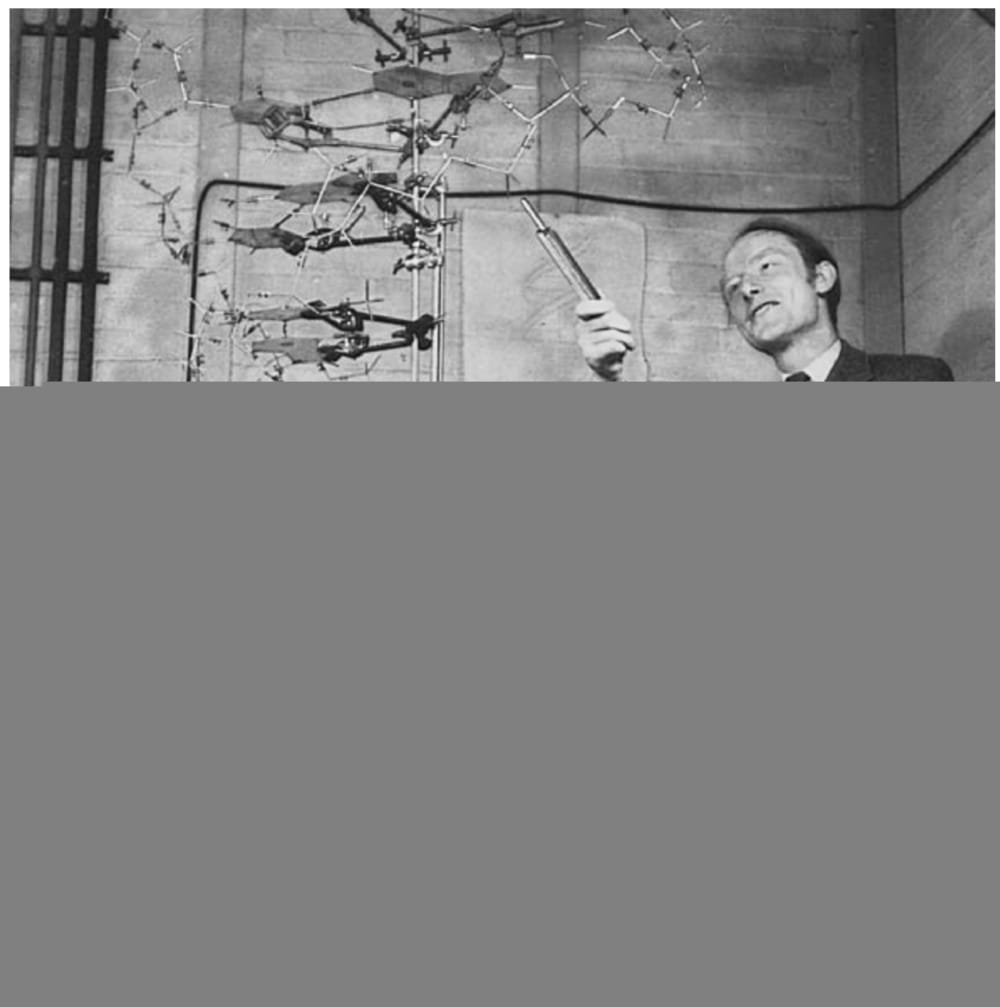

The traditional double helix configuration of every biologist’s favourite acid, DNA, is a common sight in the media. It’s on textbook covers, in adverts and even in logos attempting to convey scientific superiority, but which are really playing on the naivety of the general public (anti-aging creams, I am looking at you). The dual swirl has been incredibly romanticised since its discovery by the biology big shots James Watson and Francis Crick, but new research is showing that this structure may not be all that DNA has up its molecular sleeve.

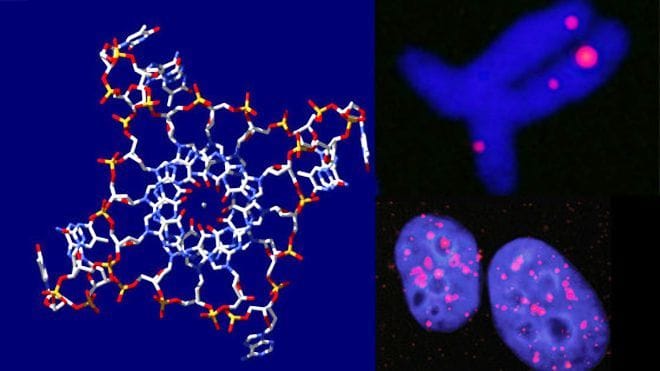

Chemists at Cambridge University, where the classical double helix structure was discovered almost 60 years ago to the day, have finally identified the quadruple helix structure of DNA in human cells. These structures, called the G-quadruplexes, form when four guanines (one of the four chemical groups that make up DNA) lie in a planar arrangement between four strands of the DNA backbone.

Data published this week in Nature, by the wonderfully named Dr Shankar Balasubramanian and his researchers shows how they have targeted fluorescent antibodies to the G-quadruplex and identified them in genetic regions that have high proportions of guanine, making this the first time these have been visualised in human tissue.

But what do these structural wonders do,if anything? They have previously been found in telomeres, the end of the chromosomes that shorten with each cellular division. Telomeres are sort of like the genetic countdown to death, and are part of the reason we aren’t immortal. As each cell divides, a little bit of each chromosome doesn’t make it to the next cell due to the enzymatic limitations that allow cell division to occur.

Telomeres are the cleaver little non-coding genetic martyrs that sacrifice themselves to ensure precious coding DNA doesn’t disappear, as they shorten instead. This shortening actually leads to a limitation in life span – as a telomere shortens to a certain point, cells may enter a state of “old age,” or die completely. When many cells do this, it can lead to organ deterioration or cause many of the diseases associated with old age.

One idea is that G-quadruplexes may stop enzymes accessing the telomere after replication. Telomerase is one such enzyme – this replaces any DNA lost at the end of the chromosome and almost reverses the genetic countdown as the chromosomes no longer shorten. With this in mind, inhibition of telomerase could be seen as detrimental to cellular longevity, although too much of telomerase activity can also lead to cancerous growth. It may be therefore that the G-quadruplex acts a mediator between too much or too little telomerase action, and maintains healthy growth levels.

Other functions are being discussed too such as the role they have in controlling gene expression, but such speculation is in need of some hardevidence to prove once and for all what these quadruple helices actually do. For now, it seems that Dr Shankar Balasubramanian and his researchers work is not over. Although we have come a long way since Watson, Crick and their Cavendish chums poured over their draft structures at the Eagle pub in Cambridge, we still have a long way in understanding the more intricate details of the genetic code.

DOI: 10.1038/nchem.1548