Japanese Sex and Pleasure

So the British Museum is putting on an exhibition on Japanese pornography? Is that even allowed?! Cast away your narrow western minds and think again. For that’s what this exhibition will do — make you think again.

So the British Museum is putting on an exhibition on Japanese pornography? Is that even allowed?! Cast away your narrow western minds and think again. For that’s what this exhibition will do — make you think again.

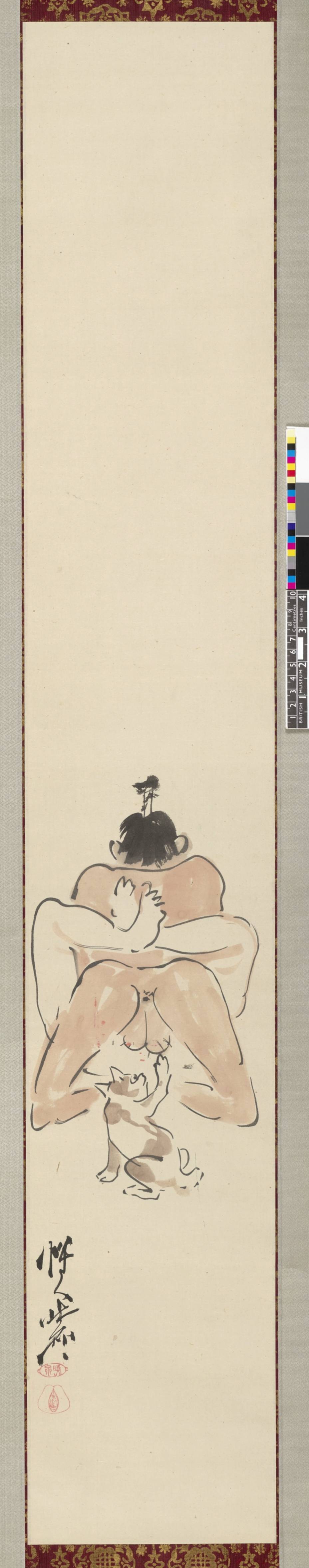

So first things first – what is Shunga? Developed in the early 17th century, Shunga (meaning “spring pictures”) is Japanese erotic art, produced by well-known artists for the enjoyment of Japanese people of all classes. From gilded scrolls to printed booklets, Shunga was available to all, and enjoyed by middle class newlyweds as much as high flying Samurais. They depict erotic scenes of various types, and with differing levels of explicitness and conventionality.

At the British Museum, great emphasis is put on the fact that these are works of art, and not just base pornography, and this is certainly true. In all the artworks shown, everyone seems to be having fun – couples, threesomes and groups – and there is no sense of objectification.

But the main difference between western pornography and these colourful, kimono clad sex-scenes is surely in the viewer. Shunga was considered an entirely acceptable part of life, and was in no way shameful or frowned upon until the mid-18th century, when the combination of a new military government and an increased western presence in Japan caused legislation to be passed against it. Thus, wandering around a gallery full of boobs, erections and some rather fanciful positions (17th century Japanese people were clearly more flexible than the average 21st century European) there is a feeling of enjoyment, amusement, interest, but no embarrassment or awkwardness – these pictures feel natural and acceptable.

As you wander round the exhibition, amongst such artworks as How the Jewelled Rod Goes In and Out, make sure you read the translations of the Shunga captions – most pictures have the lover’s conversations written in the margins. These complete the Shunga, and are often funny dialogues, saucy poems or just the sort of things you wished you hadn’t overheard through your housemate’s door. Before you leave, make absolutely certain you have had a good look at The Dream of a Fisherman’s Wife – those octopodes have got their tentacles everywhere.

All in all highly worth a trip – though be warned. If, like this author, you look young enough to get ID-ed when buying scissors in Tesco, be aware that it may be embarrassing being asked if you’re old enough to view the exhibition unaccompanied.