Get your tats out

Lauren Ratcliffe looks at some great tats

If you were to get a tattoo what would it be and why? Think about it for a moment. Perhaps you already have one. Does it represent anything important to you or is it purely aesthetic?

For Danzig Daldaev, tattoos shaped his life. He was born in Russia in 1925 and condemned in 1948 by the KGB to work as a warden in Leningrad Prison – as a ‘son of the enemy’. He devoted his life to recording tattoos of inmates and documenting their different meanings. What was, at first, a curiosity quickly developed into an obsession and over 50 years he accumulated a catalogue of over 3000 examples.

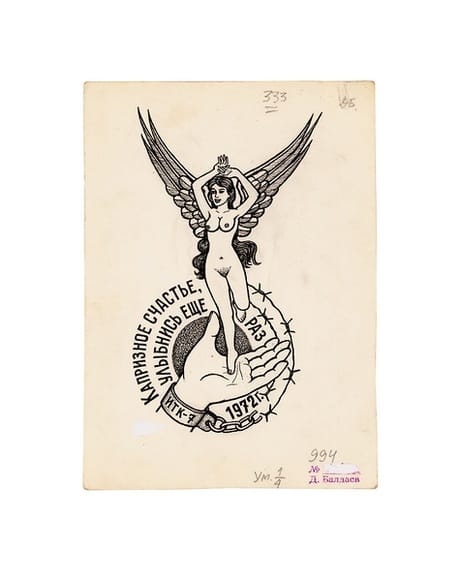

Tattooing within prison was illegal and severely punishable but on discovery of Daldaev’s project, the KGB decided to support him in hiswork. His drawings provided them with an invaluable criminal record of a prisoner’s life history; everything from previous crimes, birthplace, aspirations and even sexuality could be found out from their tattoos.

One example is of a winged woman dancing on a hand. The text reads ‘Oh, fickle fortune, smile on me once more’. It describes the thief’s desire to commit a single large-scale theft, which would allow him to give up his life of crime.

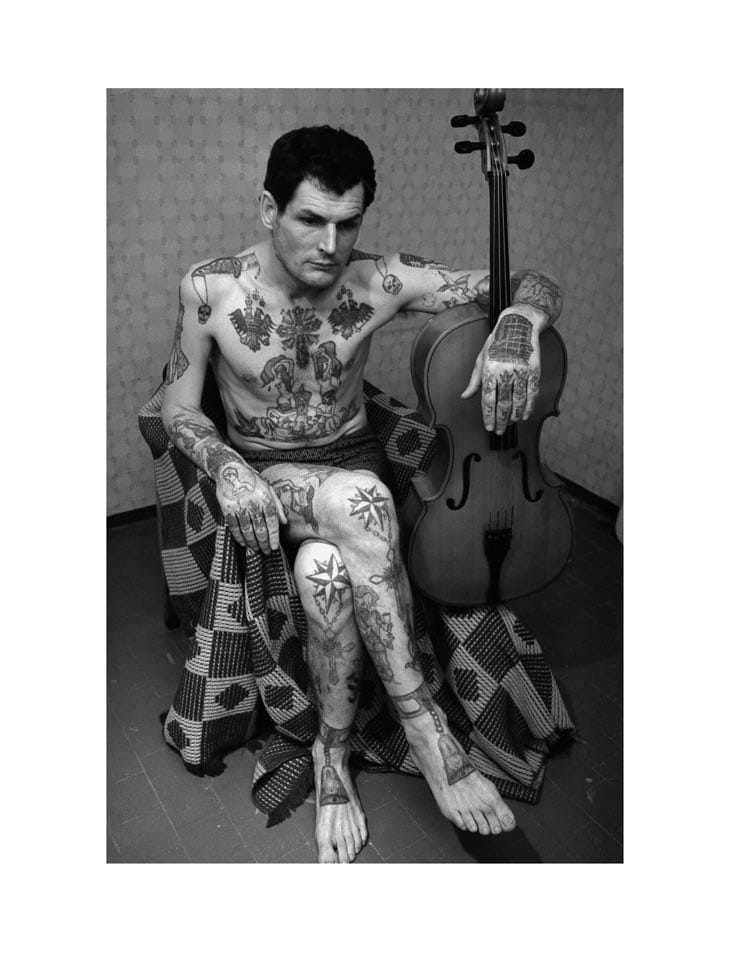

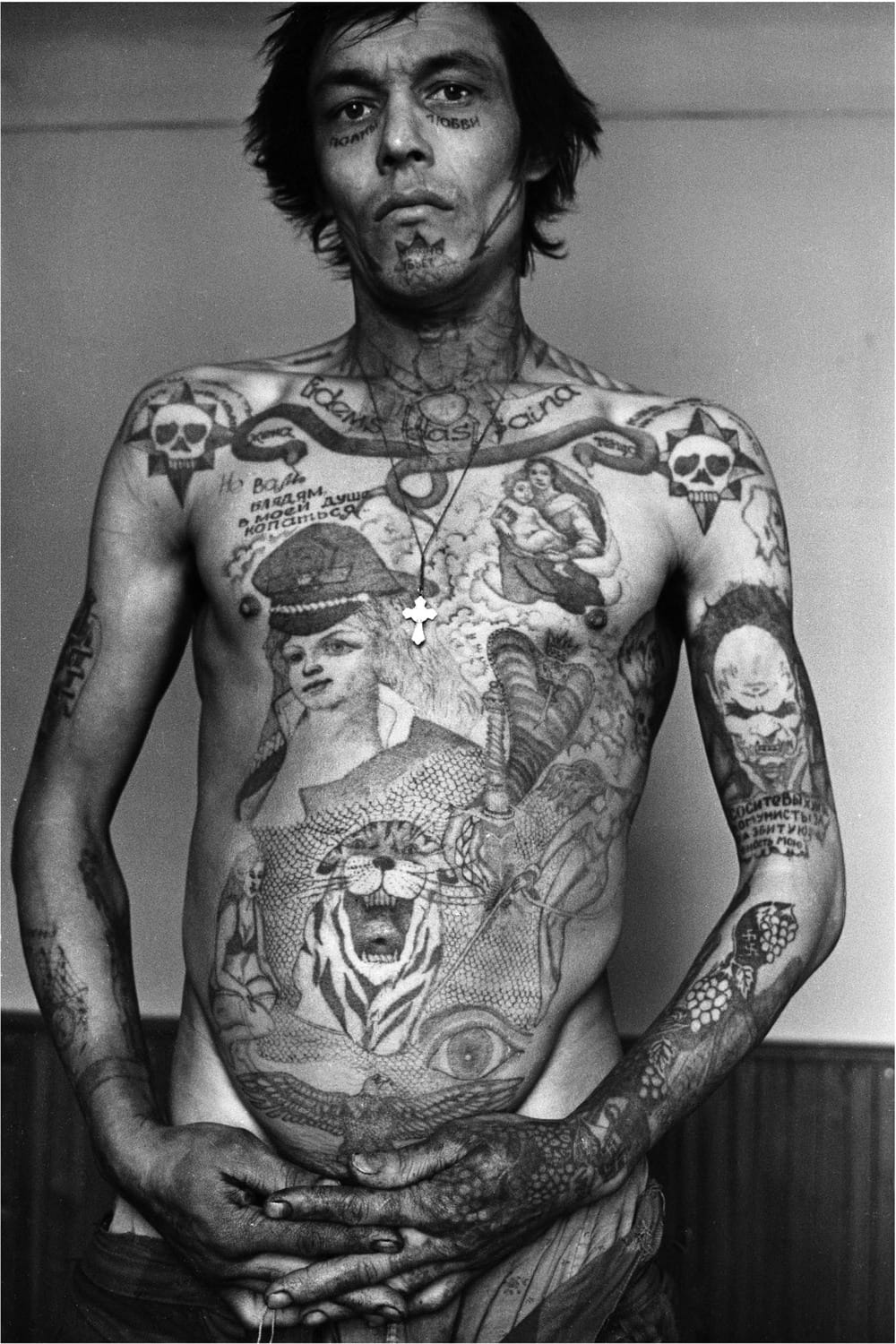

Running in parallel with Daldaev, between 1989 and 1993, was Sergei Vasiliev, brought in to formally photograph this underground Russian criminal language. In his intimate photographs we see his subjects stripped bear, openly exposing their adorned bodies to the camera. We see pride and honour in their faces but we also sense an element of reserve and serenity. His subjects are both vulnerable and strong, which I found part of the sheer fascination that his photographs evoke.

Walking around this exhibition I was drawn to the symbolism of the tattoos and questioning what they meant and why they were there. The mystery behind the portraits was what initially fascinated me and translating the illustrations emphasised howmuch the tattoos acted as a secret language in the Russian criminal underworld.

If we look further into the picture of the ‘Man and the Cello’ we see tattoos of the ‘thieves’ stars’ which openly display resentment and bitterness towards authority and can be read as ‘I will not kneel before the police’. Furthermore the manacles on hisankles signify that he has served sentences of over five years. But what I found most striking was the juxtaposition between the sense of vulnerability and gentleness in his expression and the tattoos of the daggers through his neck, which symbolise that he had committed murder while imprisoned and is available to hire for further assassinations.

Within the criminal society tattoos were used as a form of hierarchy, a man bare of tattoos would be of the lowest status whereas one adorned from head to toe would be almost untouchable. The temptation to boost your status by getting unearned tattoos is therefore great. However, considered a serious insult, if found to be displaying ‘false’ tattoos you would be beaten, raped and have them forcibly removed.

Later, in 2003, a graphic design company named FUEL brought both Daldaev and Vasiliey’s work together and formed a Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, made of three volumes. It displays all the drawings and photographs collected from the men’s joint obsession.

Go visit this exhibition for yourself. The Saatchi Gallery is just a ten minute walk away on Kings Road. Gaiety is the Most Outstanding Feature of the Soviet Union is on until May 5 and entry is free of charge.