Getting to the points of Lichtenstein

40 years of comic book trippyness

“Whaam!” is probably one of the most reproduced pieces of art on the planet. That bold comic style, that distinctive script, the perfect coloured dots... The piece is so distinctively Lichtenstein that it has perhaps come to define him as an artist. However as this retrospective shows, Roy Lichtenstein is so much more than that.

Around the time when he was playing around with comic strips and ‘Benday dots’, Lichtenstein was also experimenting with sculpture, and while I am not normally a fan, I could not help but enjoy some of his massive monochrome installations. Perhaps it is because I am quite into my writing (and stationery!), but an absolutely giant version of one of those classic ‘compositions’ notebooks got me genuinely excited about the potential for the massive stories and ideas they might contain. Meanwhile I found myself unexpectedly moved looking into one of his ‘mirrors’, and finding that I had no reflection; as though he had somehow managed to immerse my character completely within his art. Lichtenstein has a way of looking at things, a way of understanding both the cultural identity and physical geometry of his subject matter, through which by reducing them to lines and colours he somehow manages to make them say more.

In contrast, the comic strip paintings that made Lichtenstein famous did little for me. Perhaps it is because by now they have become so overused, so synonymous with the very idea of pop-art, that it is kind of impossible to have a fresh opinion about them. Also, not being much of a comic-reader myself, I have very little pre-Lichtenstein comic imagery in myhead for the pieces to play off of or tap into. Meanwhile the commentary he makes in the pieces about gender roles in American society are, I think, better expressed by his earlier and simpler works.

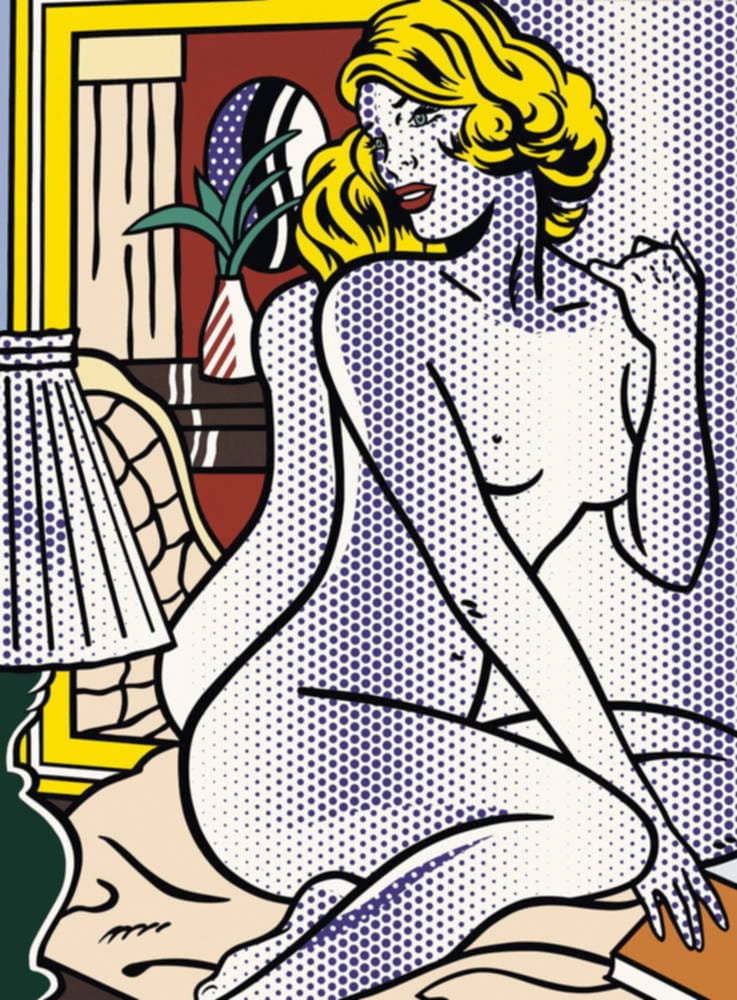

However, Lichtenstein’s interpretation of the subject of female nudes is the only one I have ever liked. I am not sure why, although perhaps it is because the naked women he depicts are having fun for once. For the first time ever, I did not question why these women were naked and vulnerable, nor his agenda, but instead appreciated his classic dotty, colourful treatment of them, the beautiful curved lines, the clever layering of patterns and imagery. In fact, such is Lichtenstein’s sensitivity to the social context of his work that the women’s choice and style of clothes, had they been wearing any, would probably have said more about them and in that way been more distracting than their nakedness.

His unusual series on landscapes and seascapes however were not quite so powerful or engaging for me. It was not that they were not technically good, or emotive, but by restricting himself to sparse broad brushstrokes or sheets of bendy plastic, Lichtenstein prevented his own distinctive style from emerging through. (It does not help that the depiction of a sunset has been done many times before, and by some very, very good artists.) He also produced some fairly weird and abstract installations during his ‘modern’ phase, such as a recreation of a classic red velvet rope strung between two golden posts, such as one might find in a fancy theatre, that seemed just too far removed from any human touch for me to emotionally respond to.

But that is the magic of a retrospective. By spanning over 40 years of work of an incredibly interesting and surprisingly varied artist, you feel like you really are getting a chance to see everything Lichtenstein did; the good, the bad and the ugly. And by seeing everything, from his self-conscious early works and studies, before he had really found his footing as a pop-artist, to his later experiments with the styles of artists wildly different to his own, you begin to understand Lichtenstein in some way, and realise that he is quite a special artist. Every piece of his art seems completely un-self-centred and yet distinctly his. He has real talent but does not make you feel guilty or intimidated for not having the same. Most of all, Lichtenstein seems to just really enjoy making his art.